followthethings.com

Home & Auto | Gifts & Seasonal

“Banksy’s Slave Labour“

Street art by Banksy.

Photo of the original artwork in situ above. Whereabouts and condition currently unknown.

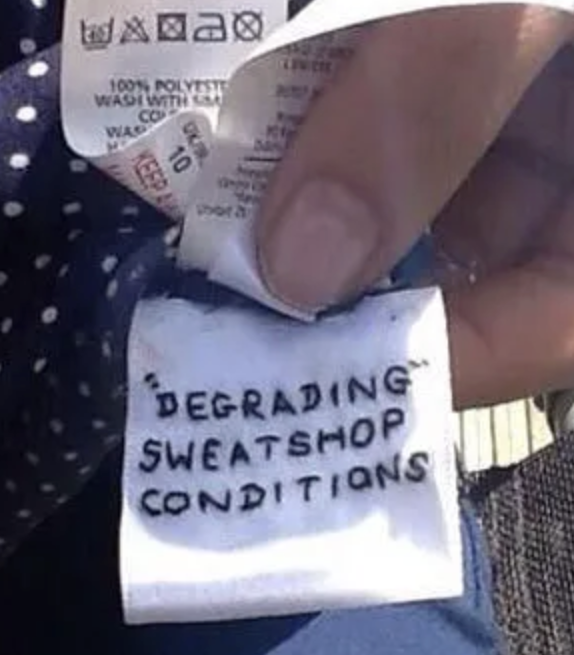

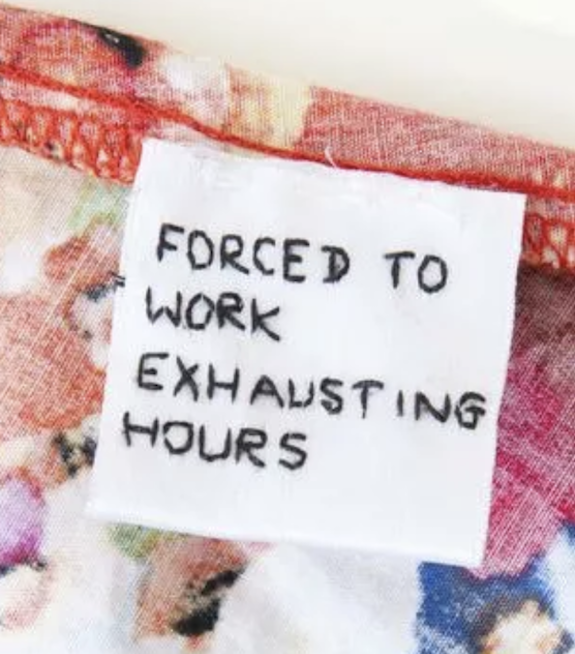

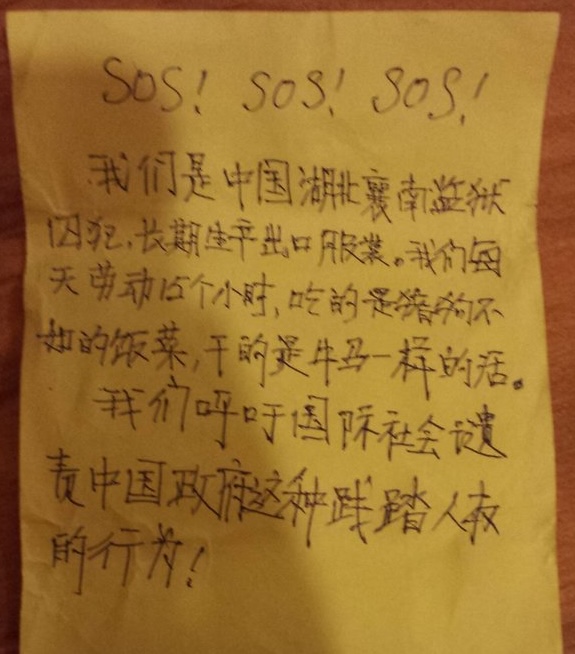

It’s 2012. Queen Elizabeth’s Diamond Jubilee is being celebrated in the UK. The London Olympics are also taking place. There’s Union Jack bunting everywhere. It’s cheaply and readily available in discount stores like Poundland. Including one in Wood Green, South London. Along a street where the Olympic torch relay may have passed. This is where the anonymous celebrity British street artist Banksy paints a mural of a child hunched over a sewing machine, making this bunting in India. Physical bunting is part of the work. It’s hung up on the wall and spills onto the pavement. Banksy, as usual, explains little or nothing. Commentators say it’s inspired by a 2010 exposé of child labour in Poundland’s supply chains. Like other examples of Banksy’s street art, it quickly makes the news, people visitfrom afar, locals claim it as theirs, and it’s stolen and auctioned on the international art market. Trade justice activists love it when their work goes viral. This story was everywhere. This image of child labour in pound shop supply chains was reproduced countless times. But this viral story wasn’t, unfortunately, about trade injustice. It did’t put pressure on Poundland, or any other retailer, to remove child labour from their supply chains, to improve workers’ pay and conditions, or to achieve any other trade justice goal. The story that went viral was about this Banksy being stolen and auctioned in Miami the following year and, later, in London for hundreds of thousands of dollars. It’s about who owns this work, who has the right to sell it, where it belongs and the irony of an artwork that critiques commodity cultrure becoming a commodity. Local residents argue that the work only makes sense in situ (a point that Banksy makes about all of his street art). It’s never returned but countless people around the world have not only seen it but also bought it. You can buy Slave Labour as a sticker, an ornament to hang on your Christmas tree, a framed print to hang on your wall, a stencil or wallpaper mural to recreate it on your wall. Because of the controversy about its removal and sale, it has become one of Banksy’s most iconic works. And the wall where it was originally posted is still haunted by its presence, with countless grafitti artists adding copies, versions and alternatives there. This is one of the most famous examples of trade justice art-activism. Banksy lending his celebrity status to the cause brought it into the media spotlight for months. But there’s no evidence that this helped to improve the pay and conditions of workers, younger and older, in pound shop supply chains. So what can we learn from what did and didn’t happen here? What could and couldn’t happen?

Page reference: Lydia Dean, Lucinda Armstrong, Jessica Bains-Lovering, Emily Hill, Harriet Allen & Rose Cirant-Carr (2025) Banksy’s Slave Labour. http://followthethings.com/banksy-slave-labour.shtml (last accessed <insert date here>)

Estimated reading time: 61 minutes.

Continue reading Banksy’s Slave Labour ![]()