followthethings.com

Gifts & Seasonal

“Xmas Unwrapped“

A short film edited by Toby Smith and Unknown Fields Division with Tim Maughan.

Posted in YouTube, embedded above in full.

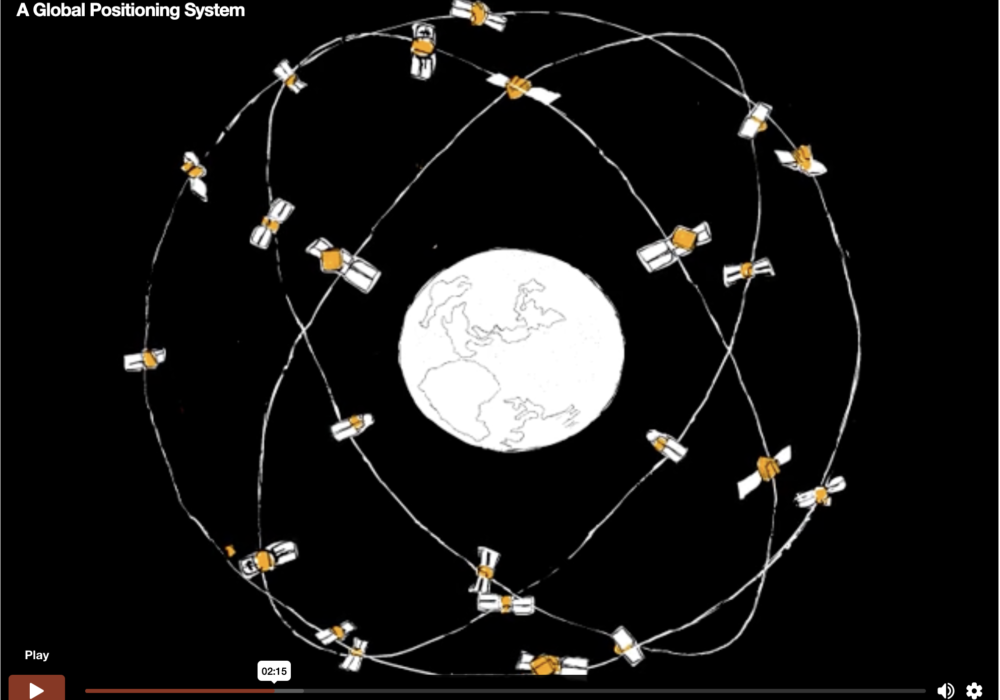

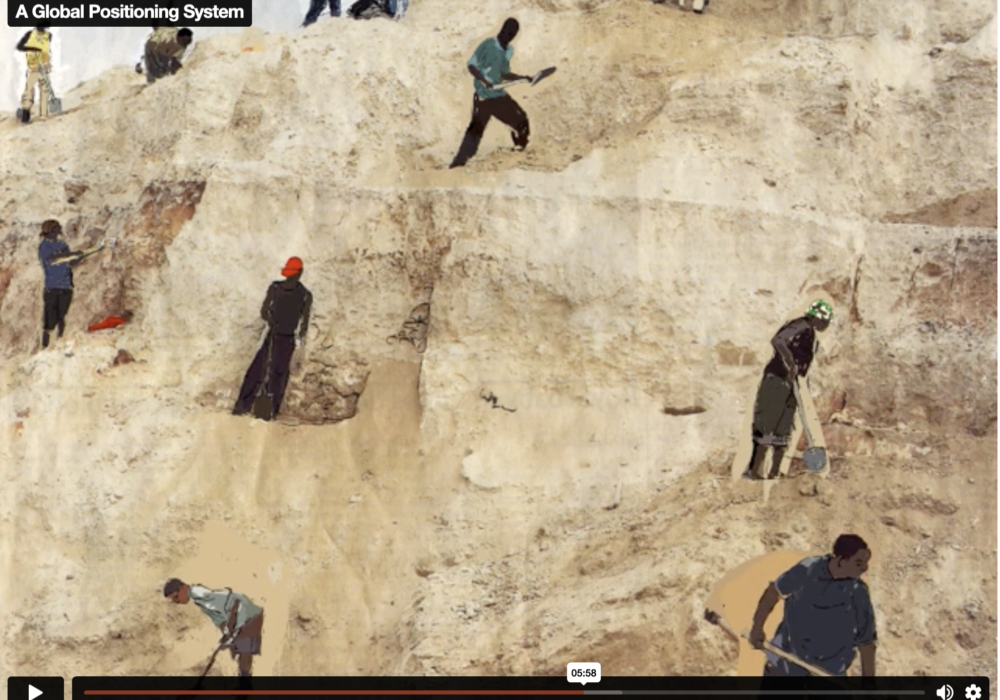

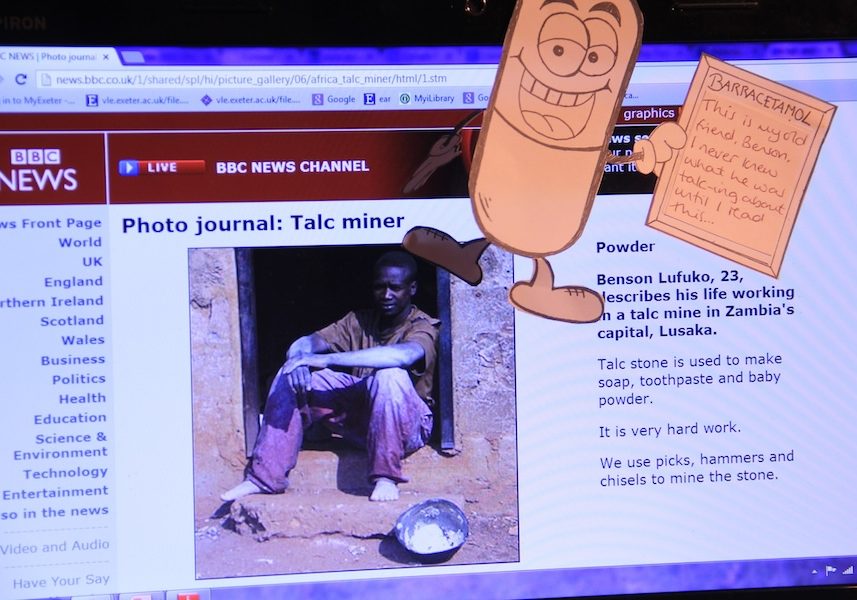

This short ‘Jingle Bells’ Chinese Christmas factory film comes from a larger initiative to rethink architecture. According to Unknown Fields Division co-founder Liam Young, ‘an architect’s skills are completely wasted on making buildings’. They should be turning their attention to the outsides that are inside them: i.e. the hidden geographies of infrastructure, logistics, commodities and connected landscapes. For ‘follow the thingers’ familiar with Geographer Doreen Massey’s concept of a ‘global sense of place’ [see this example], this extroverted sense of place may seem familiar. But there’s so much to learn from Unknown Fields’ architectural experiments. First, from the thoroughly collaborative and interdisciplinary studio practice of Unknown Fields Division. Second, from the long-running postgraduate course at the Architectural Association in London where Liam Young has taken students on infrastructural ‘expeditions’ for many years. Third, from the writers, filmmakers, data-visualisers and programmers who have accompanied these expeditions and produced its highly-professional and publicly eye-catching work. Xmas Unwrapped is one such output – a ‘Christmas card’ – from a 2014-15 expedition called A World Adrift. We’ve asked our ‘Geographies of material culture’ students to watch it before writing their coursework over the Christmas break. It doesn’t have a explicit message, but it’s catchy and thought-provoking. There’s observational footage of people working in a basic factory space in China making Christmas decorations and Santa hats by hand. Other people box these up, load them into a container, and the film finishes with a view from bridge of a container ship sailing out to sea, taking them to their consumer destinations. If you watch it with the sound down and the film footage is undramatic. People just work. Their tasks are repetitive. Their heads are down. They say nothing. The footage does not aim – it seems – to evoke any emotion in its audience. But turn up the volume and it’s accompanied by a choir of children singing ‘Jingle Bells’ in Cantonese. And it’s this combination of film footage and music that provokes a reaction. It’s catchy. This film is a gentle form of trade justice activism. You could call it an appetiser. It’s trying to ‘pop the bubble’ of Western consumption by ‘joining the dots’ to Chinese factory production. It does not explicitly address trade injustice, exploitation, labour rights or any consumer or producer activism relating to this. The factory and logistics workers it features don’t have a voice in their representation. Unknown Fields Division isn’t making this work because they want audiences to do anything. Just to know and to reflect on the fact that its audience member’s things are made by people elsewhere in the world. This film can be used as a brief and gently provocative spark for discussions of trade (in)justice in any classroom [like another example on our site, Handprint] but also – especially – around a Christmas dinner table. Because Unknown Field Division‘s expeditions have so many people on them, this film is the tip of an iceberg. The most noticeable impacts it has are not on its audiences [as far we can see] but on the expedition’s students and collaborators. They produce other work that brings attention to this Christmas story, and to the wider project on architecture’s dependence on supply chain logistics. Follow the arguments below.

Page reference: Ian Cook et al (2025) Xmas Unwrapped. followthethings.com/xmas-unwrapped.shtml (last accessed <insert date here>)

Estimated reading time: 39 minutes.

Continue reading Xmas Unwrapped ![]()