RELATED INGREDIENTS

INTENTIONS

Pop the bubble

Cross cultures

Show what’s possible

TACTICS

Include emotion

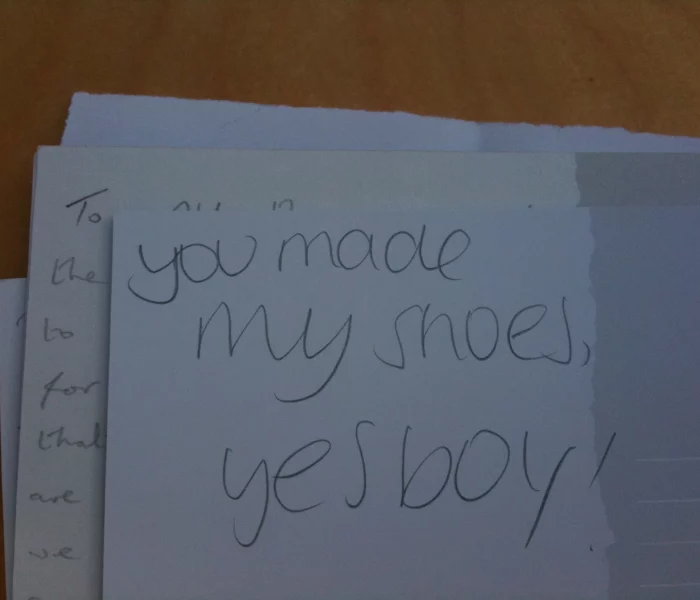

Humanise workers

Humanise things

Make it familiar

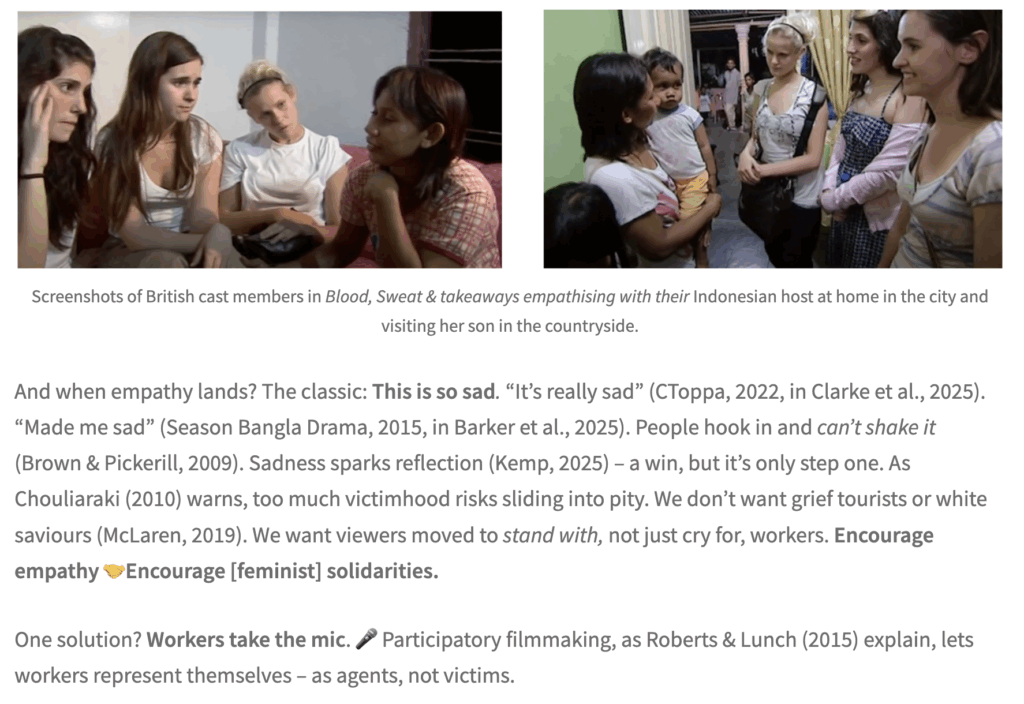

Encourage empathy

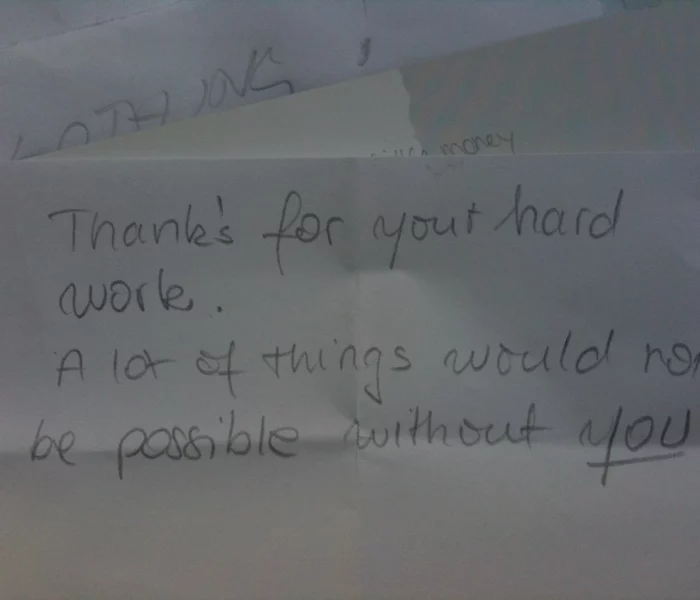

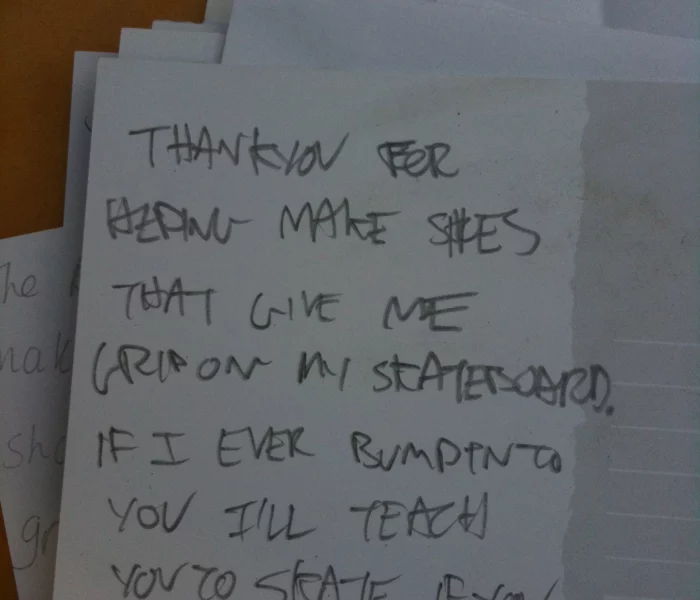

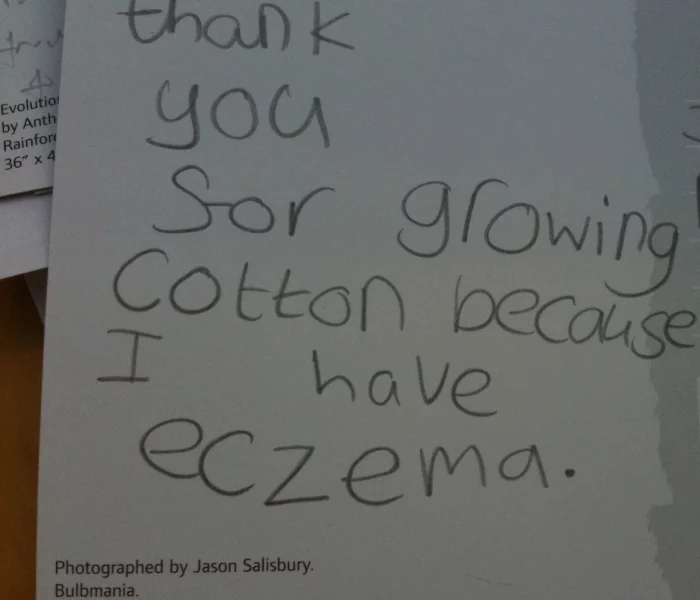

Encourage thankfulness

Follow the people

Find a character

Be the character

Involve a celebrity

Find lost relations

Bring people together

Spend some time

Cultivate relationships

Encourage feminist solidarities

Make it together

Walk the walk!

Have a theory of change

RESPONSES

I know how they feel

I just cried

That’s my story

This gives me hope

These people are inspiring

Thank you

We We We

It’s so lightweight

Call youselves feminists?

What’s the point?

Charity begins at home

IMPACTS

I get what it’s like

Now we’re talking

Activism is inspired

Can’t tell

EXAMPLES

HANDBOOK PAGES

Jamelia: whose hair is it anyway?

‘I found this in a box of Halloween decorations’

Letter from Masanjia

Made in Dagenham

FOLLOWTHETHINGS.COM PAGES

Find the love

IN BRIEF

Cut though the greed, selfishness, competition, inequalities & exploitations of global capitalism, by finding people who care deeply & unreservedly for each other, expecting nothing in return. Don’t look back in anger, look forward with love. Of all the emotions captured and generated by trade justice activism, this is the most positive for effective change.

What’s this page?

This is a tactic page that tries to explain this tactic, illustrate it with reference to comments taken from relevant followthethings.com example pages, and gives a sense of the intentions, responses and impacts that go with it. Only a few of the handbook links work at the moment. The headings are included to give a sense of what’s to come.

… anger … should not be the emotion that motivates activism. … a more just society is developed through the emotion of love.

Hazel Biana (2021, p.132).

… love is an antidote to oppressive human-made systems of colonialism, neoliberal capitalism, white supremacy, and patriarchy.

Naomi Joy Godden & Shajimon Peter (2023 p.2).

Today we live in a money economy, where we don’t really depend on the gifts of anybody but we buy everything. Therefore we don’t need anybody. Because whoever grew my food or made my clothes or built my house, well, if they died or if I alienated them, if they don’t like me, that’s OK. I can just pay somebody else to do it. It’s really hard to create community if the underlying knowledge is ‘we don’t need each other’. So people kind of get together and act nice, or maybe they consume together. But joint consumption doesn’t create intimacy. Only joint creativity and gifts create intimacy and connection. … I think love is the felt experience of connection to another being. An economist says ‘more for you is less for me.’ But the lover knows that more for you is more for me too. If you love somebody then their happiness is your happiness. Their pain is your pain. Your sense of self expands to include other beings. That’s love. The expansion of the self to include the other. And that’s a different kind of revolution.

Charles Eisenstein (2011, np).

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipiscing elit. Quisque faucibus ex sapien vitae pellentesque sem placerat. In id cursus mi pretium tellus duis convallis. Tempus leo eu aenean sed diam urna tempor. Pulvinar vivamus fringilla lacus nec metus bibendum egestas. Iaculis massa nisl malesuada lacinia integer nunc posuere. Ut hendrerit semper vel class aptent taciti sociosqu. Ad litora torquent per conubia nostra inceptos himenaeos.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipiscing elit. Quisque faucibus ex sapien vitae pellentesque sem placerat. In id cursus mi pretium tellus duis convallis. Tempus leo eu aenean sed diam urna tempor. Pulvinar vivamus fringilla lacus nec metus bibendum egestas. Iaculis massa nisl malesuada lacinia integer nunc posuere. Ut hendrerit semper vel class aptent taciti sociosqu. Ad litora torquent per conubia nostra inceptos himenaeos.

Love goes beyond self-love and love of others. It is ‘an ethos of connectedness, both with the spirit within ourselves and with others. Feeling connected very much contributes to the finding of wholeness and definitely to love’ … Love should lead to the eventual ‘healing’ of the world. A healed world is a world wherein oppression has been eradicated.

Hazel Biana (2021, p.134).

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipiscing elit. Quisque faucibus ex sapien vitae pellentesque sem placerat. In id cursus mi pretium tellus duis convallis. Tempus leo eu aenean sed diam urna tempor. Pulvinar vivamus fringilla lacus nec metus bibendum egestas. Iaculis massa nisl malesuada lacinia integer nunc posuere. Ut hendrerit semper vel class aptent taciti sociosqu. Ad litora torquent per conubia nostra inceptos himenaeos.

If people are reminded that love exists, will it make the right kind of love the norm? … There must be an eagerness for dialogue between the one who gives and receives love.

Hazel Biana (2021, p.135).

RECOMMENDED READINGS

Hazel Biana (2021) Love as an act of resistance: bell hooks on love. in Soraj Hongladarom & Jeremiah Joven Joaquin (eds) Love & friendship across cultures. Singapore: Springer Nature, p.127-137

Naomi Joy Godden & Shajimon Peter (2023) The love ethic: love and activism for ecosocial justice. in Magdalena Grobbelaar, Elizabeth Reid Boyd & Debra Dudek (eds) Contemporary love studies in the arts & humanities: what’s love got to do with it? London: Palgrave Macmillan, p.1-14

Martin Luther King Jr. (2016)The Three Dimensions of a Complete Life – April 4, 1967. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GU3AnO_PJGU [last accessed 2 May 2024]

Ana María Munar (2018) Dancing between anger and love: reflections on

feminist activism. Ephemera: theory & politics in organisation 18(4), p.955-970

Transparent Film (2011) Occupy Wall St – The Revolution Is Love with Charles Eisenstein. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BRtc-k6dhgs [last accessed 2 May 2024]

Image credit

Icon: Love (https://thenounproject.com/icon/love-8251980/) by Kevin Diks from Noun Project (CC BY 3.0)

BACK TO HANDBOOK CONTENTS PAGE 👉

SECTION: Tactics

by Ian Cook (February 2026)

![]()