followthethings.com

Electronics | Home & Auto

“A Global Positioning System“

A art work / animated film created by Melanie Jackson, first exhibited at the Arnolfini Gallery, Bristol, UK.

Two screengrabs from the film are featured above. Watch it in full on the artist’s website here.

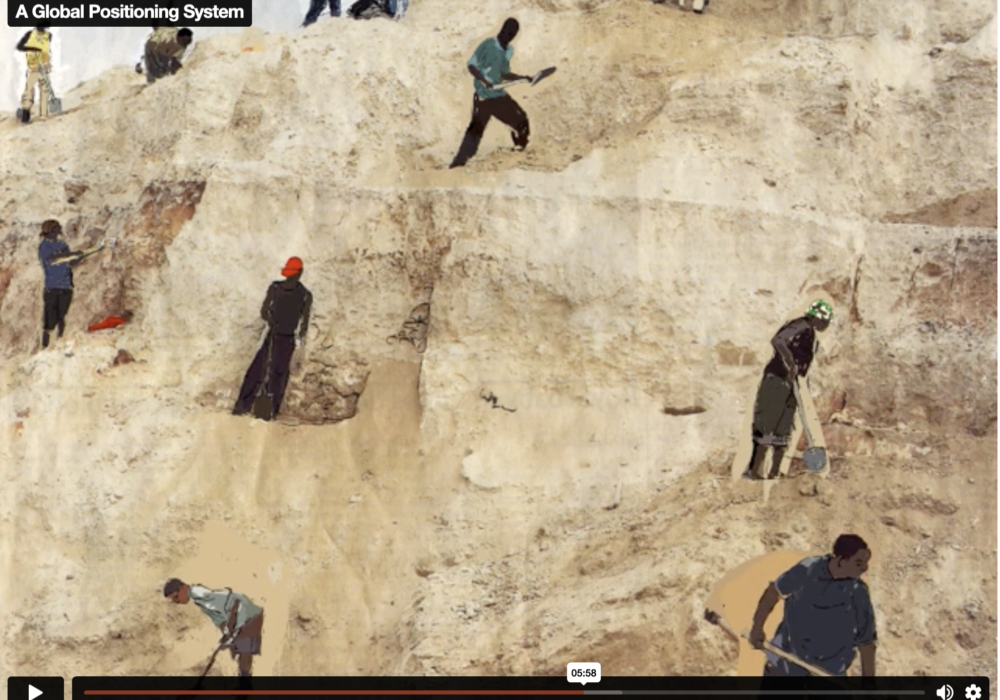

If you’re interested in finding out who makes your stuff, it’s important to make a strategic choice about what stuff is best to follow. Artist Melanie Jackson makes an excellent choice – what better to guide your way than the technology that helps to guide your way. An in-car GPS Navigation Assistant. The kind of device you could buy in the 2000s to stick to your dashboard. Type in the destination, and it would help you on your way, showing the route on screen. She gets some funding for a trip to China to visit a factory where they are assembled. But this isn’t anything like enough of the story of this thing. She looks into its in many many ingredients, and finds out where and by whom they are sourced. She reads news stories, collects photographs, and turn to drawing to bring all of these connections together into a 12 minute animated film. There’s something magical about animation. It’s obvious that animation is not an objective account of the life of a thing, but something that’s been imagined and made. Animation allows the complexities of trade to be conveyed in a way that would otherwise be impossible either because the scale of the task would be too enormous, or because permission would not be granted to access the industrial sites that matter. There’s a powerful argument that’s made about ‘follow the thing’ research that things can be – for these reasons – ‘unfollowable (see Hulme 2017). But animation – and other creative approaches to thing-following (click the ‘make the hidden visible’ tactic button) – provide means to work around this. This is a mind-blowing film. Its amazing what you can learn in 12 minutes!

Page reference: Ian Cook et al (2024) A Global Positioning System. followthethings.com/a-global-positioning-system.shtml (last accessed <insert date here>)

Estimated reading time: 20 minutes.

Continue reading A Global Positioning System ![]()