followthethings.com

Grocery

“Blood, Sweat & Takeaways“

A four-episode reality TV series produced directed & produced by James Christie-Miller for Ricochet Films for television broadcast on BBC3.

Sample scene embedded above. Full series available on Box of Broadcasts (with institutional login) here.

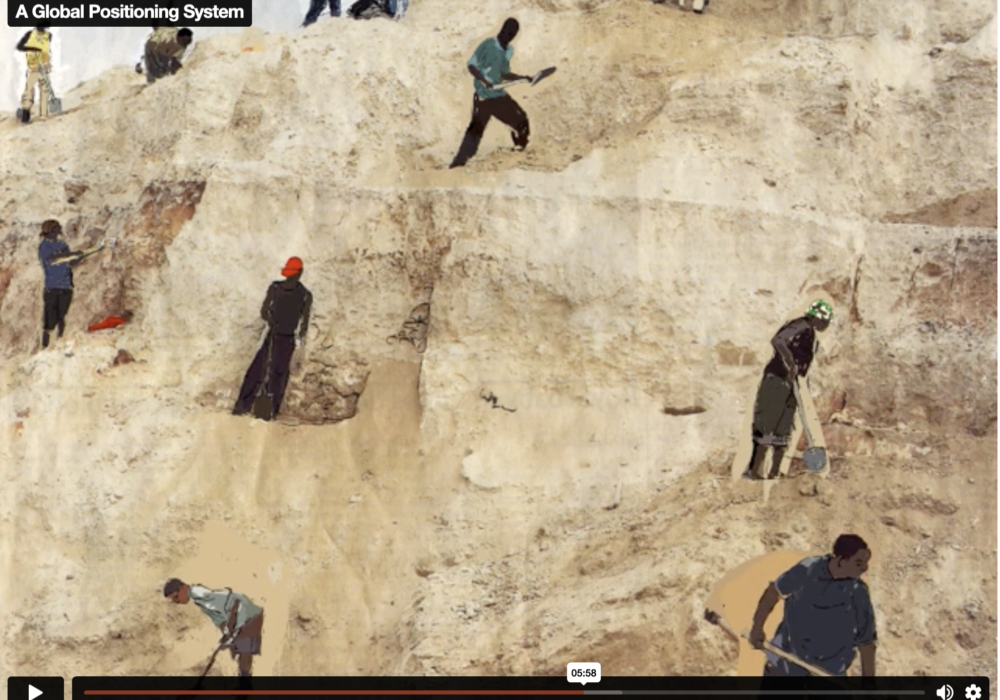

Lauren, 21, and loves luxury food. Jess, 19, is a fussy eater. Manos, 20, loves fast food. Josh, 20, loves to cook. Stacey, 20, is an ethical shopper. Olu, 25, is a fitness fanatic. But this group of multicultural Brits who don’t seem to care where their food comes from. Until they are approached by a TV company which challenges them to travel to Indonesia and Thailand and to step into the shoes of the farm, factory and trawler workers who source and process it for export. Over four episodes – on Tuna, Prawns, Rice and Chicken – they’re filmed working alongside supply chain workers, earning and spending the same 40p an hour wages, and living in the same places. They relentlessly gut, behead and loin tuna fish in a factory. They work in waist-deep mud farming prawns and up to their ankles in water in a rice paddy field. It’s hot. All they have to eat each day is a banana and a slice of bread. This is a shock to their systems. This is car crash reality TV. They crack under the pressure, retch, cry, faint, fall out, fight, refuse to work, slow down the production line, get sick, feel guilty, insult and patronise their co-workers and escape to a comfortable hotel, eat at McDonalds and get first class medical care. Olu is sent home after a fight with Manos. He’s replaced by James, a young farmer. At least he knows where food comes from. But, as they get over the shock, episode by episode, they are humbled by the experience and become more appreciative consumers. This is the second ‘Blood, sweat and…’ series broadcast by the BBC. And it’s equally successful, attracting big audiences, winning awards and being shown around the world. Its aim is to encourage young people to think about who makes their stuff, and to find their own solutions like the cast members do. Because this is reality TV, much of the discussion focuses on the cast and how ‘spoilt’ they seem to be, how terrible they are as British ‘ambassadors’ in Thailand and Indonesia, how distastasteful it is for them to ogle at squalour, and how easy it is for them – unlike the people they’re working alongside – to leave. Critics say that its reality TV format encourages an enjoyment of the casts’ meltdowns more than their thoughtful reflections. Others quibble the facts and argue that the series’ narrative arc is a work of fiction. Others say that it places too much emphasis on consumer awareness, without provinding any ideas about what viewers should do next. And there’s nothing in this series about other responsible actors in these supply chains (for a comparison, see our page on the BBC’s ‘Mangetout’ documentary here) and nothing about the need for structural change (e.g. living wage legislation). But the BBC sets up a web forum for people to discuss these issues and one cast member ends up on a late night BBC news show challenging some glib trade arguments made by a represenative of the British Retail Consortium. So, what does this TV series do for its British cast? Its Thai and Indonesian participants? The production company? The last one is easy. The success of this second ‘Blood sweat and…’ series is followed by the making of the next series. ‘Blood, sweat & luxuries’. Then, years later, TV production executives in Holland and the Czech Republic reported that it has inspired new reality TV series. The whole series was uploaded to YouTube in full in 2022, where a whole new generation of viewers – around the world – could engage with the series, its characters and its message.

Page reference: Harriet Clarke, Ben Thomson, Victoria Bartley, Katie Ibbetson-Price, Emma Christie-Miller & Harry Schofield (2025) Blood, Sweat & Takeaways. followthethings.com/blood-sweat-takeaways.shtml (last accessed <insert date here>)

Estimated reading time: 102 minutes.

Continue reading Blood, Sweat & Takeaways ![]()