followthethings.com

Health & Beauty | Home & Auto

“Barracetamol’s Family Reunion“

A cartoon character created, brought to life, placed, photographed and posted online by Elaine King, Nancy Scotford, Rosie Cotgreave, Katie Lewis, Jack Ledger, Alice Wakeley, Olivia Rogers, Dennis Yeung, Isabelle Baker and Hannah Willard.

Original interview with Barracetamol below. Family reunion photos available on Flickr here. Barracetamol’s twitter feed here. Download Barracetamol’s Family Reunion Action Pack here to print and place your own Barracetamol.

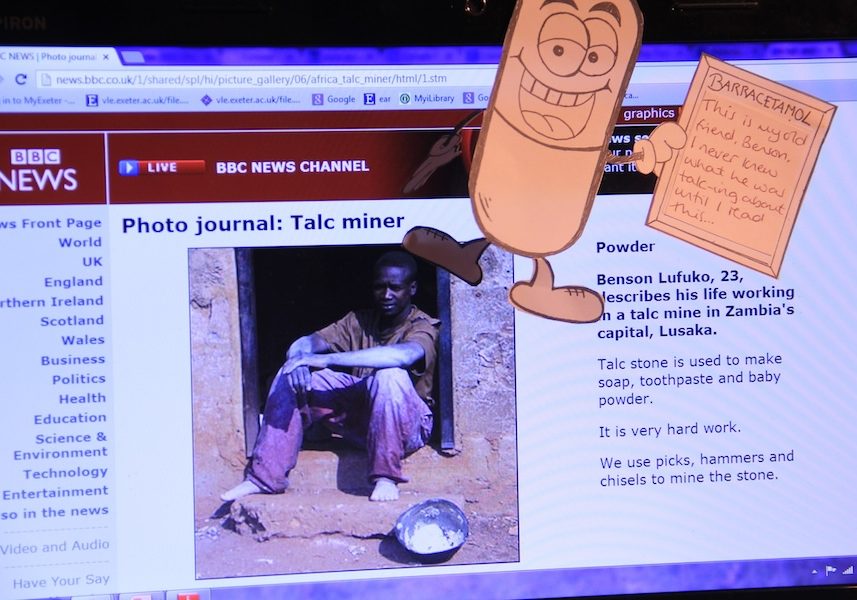

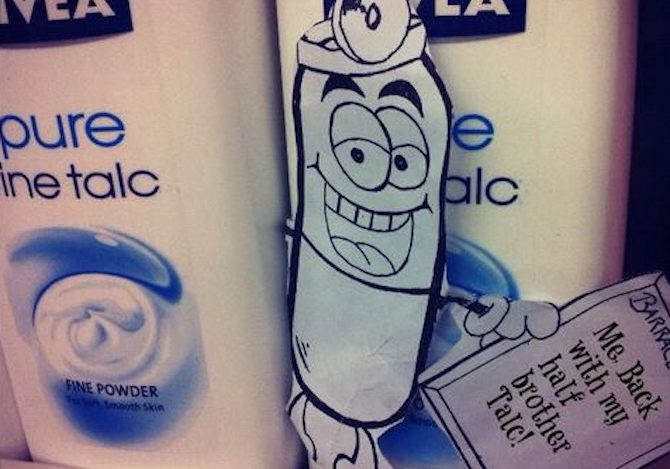

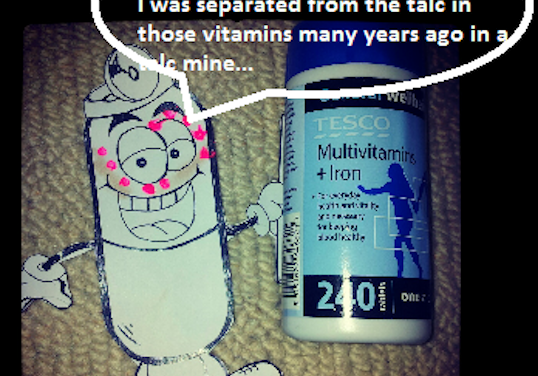

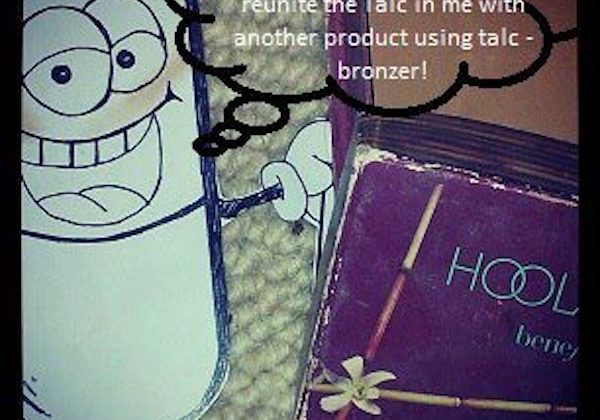

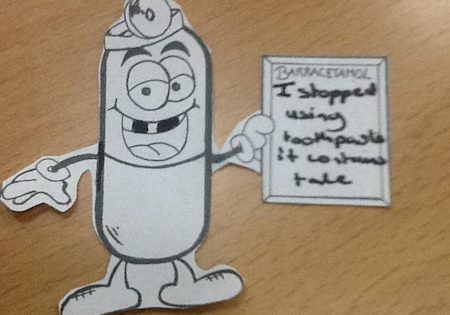

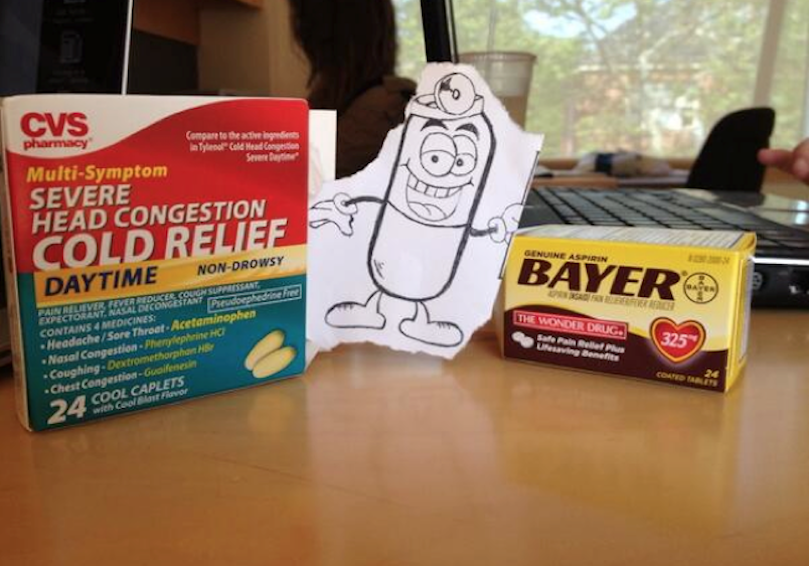

In 2012, students start the ‘Geographies of Material Culture’ by researching different examples of trade justice activism to add to the followthethings.com website (not all of them made it). Next, students who have researched different examples come together to create their own original examples of trade justice activism. They pick up some important ideas from their own research and what has already been published here on followthethings.com. They know the importance of taking commodities to pieces by looking through their ingredients and searching each one for mining, factory, farm and other human stories from their origins. They know the importance for filmmakers and activists of finding or creating a charismatic character for their audience members to relate to and empathise with. They’re familiar with literature arguing – and examples showing – that commodities have their own agentic power, can teach us things, and can be imagined coming alive and teaching us a few things. One group of students chooses something they all carry around with them: paracetamol. They look through its list of ingredients on the box. And look them up online. They find stories about talc and its miners and magnesium stearate and its connection to palm oil workers. These ingredients aren’t even in the pills, but they do help to make them. They use news stories to follow these two ingredients to their possible origins, and then turn around and look back towards their consumption. Yes, these workers and these ingredients help to make the paracetamol they carry around with them. But they start looking at the ingredients in other products, and find that talc and/or magnesium stearate are loads of other commodities too: toothpaste, paint, bronzer, beer and more. The task of the paracetamol cartoon character that they create – Barracetamol – is to go shopping with them, to find his missing relations, and to have his photo taken with related commodities with a little caption to post on his socials. He’s trying to tap into the vibe of those tear-jerking family reunion shows on TV. A familiar genre. The group’s creative process seems silly. The students enjoy it. They find it funny a lot of the time. But there’s a serious message about commodity-following behind this. At a teardown-level, countless commodities have the same ingredients sourced from the same places, mined and made by the same people. So a simple ‘this comes from there and therefore I should or should not buy it’ narrative obscures the complex interconnectedness of things in the global economy. Not everything is made for its final consumer. Barracetamol tries to convey a more complex story in a relatable way. Group member Nancy imagines that these moving reunions have made Barracetamol a minor celebrity. So he’s profiled in a magazine. Below you can read the interview.

Page reference: Elaine King, Nancy Scotford, Rosie Cotgreave, Katie Lewis, Jack Ledger, Alice Wakeley, Olivia Rogers, Dennis Yeung, Isabelle Baker & Hannah Willard (2012) Barracetamol’s Family Reunion. followthethings.com/barracetamols-family-reunion.shtml (last accessed <insert date here>)

Estimated reading time: 27 minutes.

Continue reading Barracetamol’s Family Reunion ![]()