FEATURED EXAMPLES

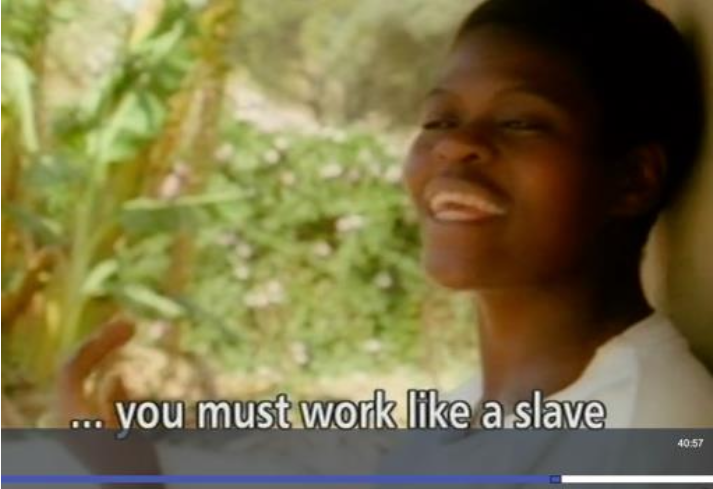

Blood, sweat & takeaways

Girl model

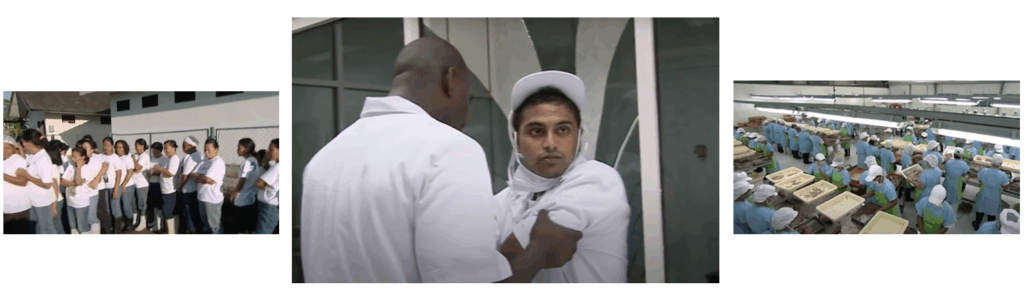

UDITA

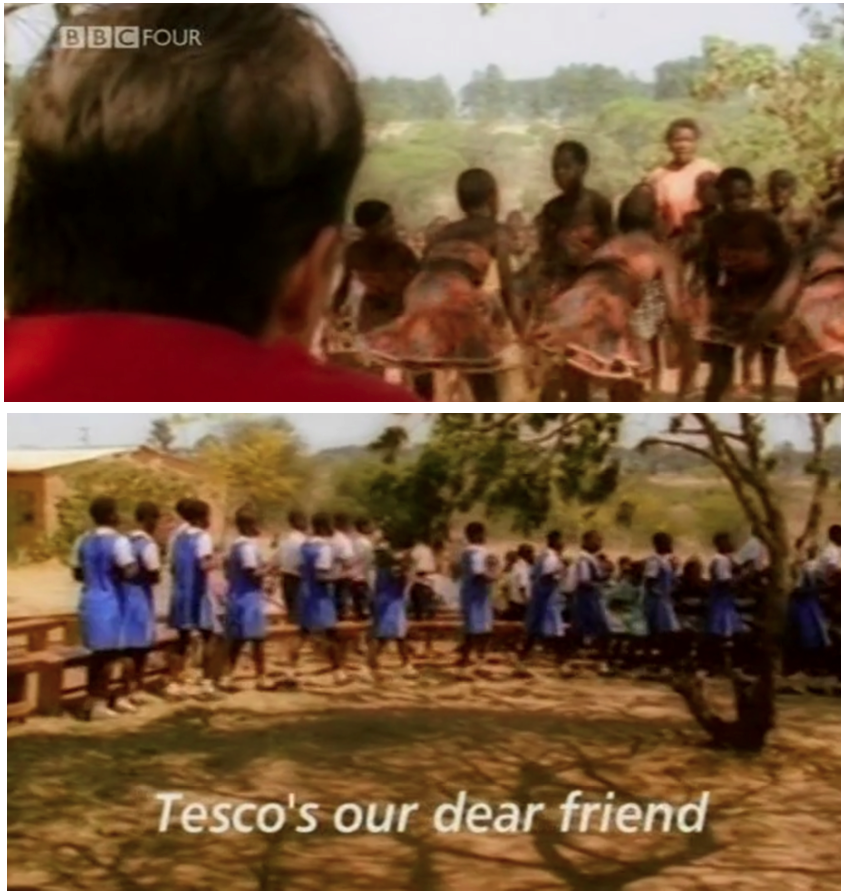

Mangetout

INGREDIENTS

INTENTIONS

Improve pay & conditions

Show capitalist evils

Change citizen behaviour

TACTICS

Tell the truth

Have a theory of change

Humanise workers

Encourage empathy

Encourage feminist solidarities

Find a character

Include suffering kids

Spend some time

Workers take the mic!

Bring managers into view

Hold ’em accountable

Blame, shame & guilt

Encourage a boycott

Place things carefully

Make a website

Stage a Q&A

RESPONSES

I know how they feel

This is so sad

Capitalism is sh*t

Wow 💥 WTF?

I’m so angry

Oh shut up

IMPACTS

Now we’re talking

Activism is inspired

Activists are recruited

Corporations change

Workers’ pay & conditions improve

“Yes, it’s small. But that’s the point“

By Sophie Burden

IN BRIEF

Student Sophie Burden has taken the ‘Geographies of material culture’ module at the University of Exeter. She’s been watching trade justice documentaries, analysing the comments on their followthethings.com pages, and making sense of them using a draft copy of ‘The followthethings.com handbook for trade justice activism’. She knows a thing or two about how trade justice documentaries work and what they can do. She’s been asked to imagine meeting a filmmaker who’s planning a new trade justice documentary. What advice could she give? Empathy is your best friend, but don’t get sloppy. Blame the right thing. And play the long game.

More about this page.

We are slowly piecing together a followthethings.com handbook for trade justice activism and are publishing draft pages here as we write them. This is an ‘advice’ page. The main text is an example of student work from the ‘Geographies of material culture’ module which followthethings.com CEO Ian ran at the University of Exeter in the 2024-25 academic year. Students watched 8 films, and read their pages on followthethings.com (with the expeption of an unfinished film called The ginger trail). They were asked to pair the comments brought together on each of the films’ followthethings.com pages with the appropriate ingredients phrases (naming their intentions, tactics, responses and impacts – show in bold below) being drafted for the Handbook. Using these phrases as a pattern language (see FAQs), students were tasked to work out how specific intentions (e.g. improve workers’ pay & conditions) needed specific tactics (e.g. flip the script) to generate different kinds of responses (e.g. this is disgusting), which could generate different kinds of impacts (e.g. audiences are empowered). [NB pages about each of these ingredients are coming soon] At the end of the module, students were asked to imagine that they had met someone who was about to make their first trade justice documentary. Drawing on what they had learned in the module, what advice could they give them on how to make it effective?

So, you want to make a trade justice documentary that really makes a difference?

Great idea!

But let’s get one thing straight: effective doesn’t just mean making your audience cry into their £5 Primark hoodie. That’s easy. The hard bit? Sparking activism that actually changes things. You’ve got to wade into global trade’s murky world and make a dent, however small, to improve pay and conditions for the workers who keep it running.

That’s the heart of trade justice activism. It targets the deep unfairness baked into international trade – the fact that 85% of the world hustles to keep a privileged few comfy (Campbell Stephens, 2021).

It’s about telling the truth: exposing how the global economy puts corporate profit over human rights and workers’ dignity (Hadiprayitno & Bağatur, 2022, Miller, 2001). And asking: who’s really winning here?

Spoiler: it’s not the workers.

The goal? Democratise trade governance – fairness, sustainability, accountability. Your film can’t just show suffering; it’s got to hit harder. Rip back the curtain on capitalist evils and spark reflection that changes citizen behaviour.

And how do you get there? Enter your ✨ theory of change✨ . Duncombe (2023) calls it the Artistic Activism model: real change happens when activism blends emotion, ideas, and action. A great trade justice documentary makes us feel (empathy, anger), think (about justice, fairness, solidarity), and do (push for change).

Here’s how you make that happen…

Empathy is your best friend – but don’t get sloppy

You don’t just want audiences to witness suffering – you want them to feel it. That’s when you get under their skin.

Empathy is the magic sauce. “A pathway to audience engagement” (Nash & Corner, 2016). But fragile. Your mission? Make people care, not just pity. As Krznaric (2007) puts it, true empathy is an imaginative leap into someone else’s world.

But if all you spark is tears and a shrug, you’ve missed your moment. Empathy without direction? Dead end. Turn that feeling into something stronger: encourage [feminist] solidarities.

So how? First tactic: find a character. Or a few!

Canning & Reinsborough (2012) spell it out – personal stories are what hook people in and encourage empathy. Nåls (2018) adds: we need full human backstories, not snapshots. Dreams, struggles, strength. Faces, not faceless crowds.

That said – choose your characters wisely! Cough, Cough…..Blood, Sweat and Takeaways. Six Brits dropped into Southeast Asian factories to “lift the veil on voiceless workers” (Rees, 2009 in Clarke et al., 2025). But my standout memory of episode one: Olu, the bodybuilder, brawling in a tuna 🐟 factory and smashing a window 💥 . Iconic.. for all the wrong reasons. And wow, did viewers have thoughts t. “It was ruined by a fight” (Anon, 2009 in Clarke et al., 2025). “Our great nation couldn’t have chosen worse ambassadors” (Whitelaw, 2009 in Clarke et al., 2025). Yeah. Not quite the “takeaway” they were going for. 😬

Bonus tactic: include suffering kids. Brutal but effective. Bruzzi (2018) and Aguiar et al. (2008) show nothing hits harder than childhood innocence wrecked by adult-made systems. That’s emotional dynamite. 💣

Then: spend some time with workers. Humanise them. That’s how you swap sympathy for real empathy. Cook & Woodyer (2012) say good films “re-attach” workers to fetishised products, showing real people with struggles and strength. Slow it down, keep the footage raw (Cuff et al., 2016). Show whole lives – not just snapshots.

And now, the gold-standard examples.🏅

Girl Model. Forget glitz – this film drags us into the dark side of (child!) modelling. Following Nadya, 13, tape-measured, plucked from Siberian, bye family, flown to Japan, wide-eyed and hopeful. What unfolds? Debt, loneliness, shattered dreams – and one deeply creeptastic scout. The camera lingers, vérité-style, as her world cracks. (Tactics ✔ ✔ ✔ ). It worked. Viewers felt it. An “Uncomfortable, eerie….saddening” film that “sticks with you” (Almachar, 2012 in Hambly et al., 2025). “I wanted to give Nadya a hug, because I felt her pain” (DisturbedPixie, 2013, in Hambly et al., 2025). Bang – empathy landed. I know how they feel. 😎

Blood, Sweat and Takeaways? 🩸 💧 🍔 – Despite casting hiccups, it nailed key moments too. Six youngsters in factory grind, each with a backstory. Find some characters. Pick your Brit to feel with (Cuff et al., 2016). And the win? We met the workers – not props.. And the audience noticed. @myoldvhstapes (2022, in Clarke et al., 2025) summed it up: “The young woman….at the chicken plant spoke of her little son, her plans for his future, her need to make money for him.” Brass (2007, in Clarke et al., 2025) nailed the takeaway: “Migrants are portrayed as ordinary people, like us… same kind of hopes and fears.”

And when empathy lands? The classic: This is so sad. “It’s really sad” (CToppa, 2022, in Clarke et al., 2025). “Made me sad” (Season Bangla Drama, 2015, in Barker et al., 2025). People hook in and can’t shake it (Brown & Pickerill, 2009). Sadness sparks reflection (Kemp, 2025) – a win, but it’s only step one. As Chouliaraki (2010) warns, too much victimhood risks sliding into pity. We don’t want grief tourists or white saviours (McLaren, 2019). We want viewers moved to stand with, not just cry for, workers. Encourage empathy 🤝Encourage [feminist] solidarities.

One solution? Workers take the mic. 🎤 Participatory filmmaking, as Roberts & Lunch (2015) explain, lets workers represent themselves – as agents, not victims.

Enter Udita: the blueprint. Five years, no Western narrator, no saviours. Just Bangladeshi garment workers telling their own stories. Factory collapse, unimaginable loss, marches, unionising, fighting back. Raw. Unfiltered. Their pain, their determination – it was contagious. Henriksen (2015, in Barker et al., 2025) nails it: “There are no passive victims. Only men and women who fight for their rights.” 💪

So yes – encourage empathy.

But keep your eyes on the prize: empathy opens the door; solidarity kicks it down.

Blame the right thing

Right! We’ve ruffled some feathers now. Emotions are high, eyes are wide. But the real question: who’s to blame for all this pain?

Spoiler: not the consumer. ❌

We’ve all seen the blame, shame and guilt tactic in action. The classic move: “Look at your cheap T-shirt! Look what you’ve done!”

Sure, the thinking is noble – let guilt spark change (Barnett & Land, 2007). But in practice? It flops.

Guilt paralyses, triggers defensiveness, and sends audiences straight to ‘oh shut up‘ mode (Sandlin & Milam, 2008; McLaren, 2019).

Take Blood, Sweat and Takeaways. Guilt wasn’t the goal – but when you show British supermarkets and reel off stats about how much tuna we guzzle? It hit a nerve. As Simon (2009, in Clarke et al., 2025) groaned: “Now this programme wants to make me feel guilty about eating tinned tuna – one of the few stress-free meal options I thought I had left.” Me? Smug vegetarian mode activated: popcorn out, blaming my fish-loving friends. Not my problem.

Totally missing the point.

The message? Lost for me + Simon. Swapped for a dinner-time blame game.

And guilt-tripping? Not just unhelpful – downright unfair.

Sure, you could encourage viewers to boycott the product.

And resist endless marketing. And fight social pressure. And not shop like their friends. And spend more cash (but only on the right brands). And spot greenwashing. And cross-check the supply chain. And decode labels. And dig into corporate reports. Perhaps a degree in ethical consumption just to be sure. 😉

Fair? Yeah … no.

So, filmmaker: drop the guilt. If your film makes me feel like the villain? I’m out before the credits roll.

Instead. Pinpoint the villains and hold ’em accountable.

This is where your documentary punches up. ✊🏽

We’re talking corporations, governments, whole supply chains – the big players cashing in while workers sweat it out.

Your film’s job? Expose hypocrisies, rip open empty promises, and hit em where it hurts: reputation. Corporations love their glossy ethics reports – but Wagner et al. (2020) are clear: when words clash with reality, trust collapses. Your audience needs to see those cracks.

Expose. Humiliate. Shame. Them. (Bartley & Child, 2014). 😤 Mangetout nailed it. A wild ride for a humble pea: zooming between smug Brits at dinner parties and Zimbabwean fields where workers sweat for pennies. The kicker? Tesco’s buyer struts in like royalty, barking orders while workers beam – grateful for crumbs from the king’s table. A clever tactic: bring a manager into view – a villain. And it landed: “Tesco became ‘evil’ for me … when I saw [this] BBC2 documentary back in 1997” (Chapman 2010, in Cook et al 2025). Reputational damage delivered.

But don’t stop at brands. Zoom out.

Greedy supermarkets? A symptom. Capitalism = the disease 💸 – the “inequality-enhancing machine” (Wright, 2015) that keeps the whole circus spinning. Mangetout gives us a pea’s-eye view of global capitalism – bosses, farmers, consumers, trapped in a rigged game. McLaren (2019) warns, if you stop at human sob-stories without digging into the structures – you risk propping up the very hierarchies you set out to challenge. No pressure 😉

Your real win: not fixing corporations overnight, but shifting how citizens see them – and the broken system behind them. Harder to trust, harder to excuse, harder to ignore.

You want anger. ‘I’M SO ANGRY’ 😡 . Not that useless guilt-ridden kind – something better.

Slow, collective, empathic anger (Coplan, 2011). (Wink wink: thank yourself for planting those solidarity seeds earlier.) One Udita viewer nailed it: “It made me angry… United We Stand” (Season Bangla Drama, 2015 in Barker et al., 2025). Righteous fire aimed at the real culprits.

Capitalism is sh*t.

Here’s where Iris Young (2003) comes in clutch: it’s not about guilt – it’s political responsibility. We’re all tangled in this mess by everyday participation. Real change = Collective action. Pushing governments, corporations, the whole rigged game.

So let’s drop the tired “consumer blame” narrative. Your audience? They’re citizens, workers, voters, activists – with power way beyond their wallets (Hadiprayitno & Bağatur, 2021).

The long game

So, after all that righteous anger… change? It’s not coming fast. Sorry. But don’t lose hope. This is where the real magic kicks in.

Sadness fades. Anger cools. But conversations? They ripple.💧

That’s what turns a trade justice doc from a one-off gut punch into a long-haul political tool. Done right, these films slide into the cultural bloodstream – sparking awkward dinner-table debates, furious WhatsApps, late-night Googling.

Tiny shifts that start tipping the scales.

Heim (2003) calls it slow activism: quiet, persistent, woven through everyday life. No megaphones, no instant wins – but sticky + powerful.

Girl Model has no neat resolution, but it haunted. “I watched this movie a week ago and I cannot for the life of me get it out of my head” (Zippy, 2013 in Hambly et al., 2025). The dream: a film that gnaws and won’t let go. Wow 💥 WTF?

Turbo-charge those ripples! Nash & Corner (2016) say: stage Q&As, offer follow-ups, create spaces where people don’t just feel but figure out what’s next. Place things carefully.

Like Blood, Sweat and Takeaways. The BBC made a public web forum; viewers swapped tips, vented, planned. A “hub for people… discussing what we can do about it” (Christie-Miller, 2010 in Clarke et al., 2025). Now we’re taking.

Yes, it’s small. But that’s the point. Ripples grow networks, cement injustices in public memory.

And sometimes? They spark real-world wins. Activism is inspired.

Corporations can change. Mangetout + advocacy groups helped push Tesco into the Ethical Trading Initiative. Activists can be recruited. Girl Model saw one model-turned-activist pushing for legal reform.

Activism comes in all shapes: unionising, voting, campaigning, piling on pressure. More points of attack, stronger the punch. As Young (2003) reminds us: we’re all actors in this tangled system, each holding a sliver of responsibility.

The goal? Workers pay and conditions improve. But real change is slow, messy, and hard to pin down (LeBaron et al., 2022). No quick wins. Still, it beats flimsy “impact” stickers corporations love to flash and bury (Evans, 2020; Bohyn, 2025).

You won’t topple capitalism with a camera. But you can expose its cracks, pressure corporations to clean up, and – crucially – nurture a culture that refuses to forget. Wright (2015) spells it out: can’t topple it? Tame it (regulate). Escape it (build alternatives). Erode it (grow co-ops, unions).

Change is a marathon, not a sprint. Your film? One hell of a starting gun. 💥

SOURCES

Patricia Aguiar, Jorge Vala, Isabel Correia & Cicero Pereira (2008) Justice in our world & in that of others: belief in a just world & reactions to victims. Social Justice Research, 21, 50-68.

Theo Barker, Joe Collier, Annabel Baker, Lizzie Coppen & Henry Eve (2025) UDITA (ARISE). (followthethings.com/udita.shtml last accessed 2 May 2025)

Clive Barnett & David Land (2007) Geographies of generosity: beyond the ‘moral turn’. Geoforum 38(6), 1065-1075.

Tim Bartley & Curtis Child (2014) Shaming the corporation: the social production of targets & the anti-sweatshop movement. American sociological review 79(4) 653–679

+26 sources

Hélène Bohyn (2025) Omnibus Or Not, Due Diligence Is a Must: Policy Breakdown. Better Cotton, 31 March (https://bettercotton.org/omnibus-or-not-due-diligence-is-a-must-policy-breakdown/ last accessed 22 April 2025)

Gavin Brown & Jenny Pickerill (2009) Space for emotion in the spaces of activism. Emotion, Space and Society 2(1), 24-35

Stella Bruzzi (2018) From innocence to experience: the representation of children in four documentary films. Studies in documentary film 12(3), 208–224

Rosemary Campbell-Stephens (2021) Educational leadership & the Global Majority: decolonising narratives. Springer Nature.

Doyle Canning & Patrick Reinsborough (2012) Lead with sympathetic characters. (https://beautifultrouble.org/toolbox/tool/lead-with-sympathetic-characters last accessed 2 May 2025)

Lilie Chouliaraki (2010) Post-humanitarianism: humanitarian communication beyond a politics of pity. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 3(2), 107–126.

Harriet Clarke, Ben Thomson, Victoria Bartley, Katie Ibbetson-Price, Emma Christie-Miller & Harry Schofield (2025) Blood, Sweat & Takeaways. (followthethings.com/blood-sweat-takeaways.shtml last accessed 2 May 2025)

Ian Cook et al (2025) Mangetout. (followthethings.com/mange-tout.shtml last accessed 2 May 2025)

Ian Cook & Tara Woodyer (2012) Lives of things. in Eric Sheppard, Trevor Barnes & Jamie Peck (eds) The Wiley Blackwell companion to economic geography. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 226-241

Amy Coplan (2011) Understanding empathy: its features & effects. in Amy Complan & Peter Goldie (eds.) Empathy: philosophical & psychological perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2-18

Benjamin Cuff, Sarah Brown, Laura Taylor & Douglas Howat (2016) Empathy: a review of the concept. Emotion Review, 8(2), 144-153.

Stephen Duncombe (2023) A theory of change for artistic activism. The journal of aesthetics and art criticism 81(2), 260-268

Alice Evans (2020) Overcoming the global despondency trap: strengthening corporate accountability in supply chains. Review of International Political Economy, 27(3), 658-685

Adele Hambly, Elaine King, Andy Keogh, Camilla Renny-Smith, Ed Callow, Joe Thorogood & Vicky Alloy (2025) Girl Model: The Truth Behind The Glamour. (followthethings.com/girl-model.shtml last accessed 2 May 2025)

Irene Hadiprayitno and Sine Bagatur (2022) Trade Justice, Human Rights, and the Case of Palm Oil. in Elena V. Shabliy, Martha J. Crawford & Dmitry Kurochkin (eds) Energy Justice: Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan, 157-172

Wallace Heim (2003) Slow activism: homelands, love & the lightbulb. Sociological review 51(2), 183-202

Deena Kemp (2025) Comparing disgust and sadness: examining the interaction of emotion & information in charity appeals. Journal of Social Marketing (online early).

Roman Krznaric (2007) Empathy and the Art of Living. Oxford: Blackbird Collective

Genevieve LeBaron, Remi Edwards, Tom Hunt, Charline Sempéré & Penelope Kyritsis (2022) The ineffectiveness of CSR: understanding garment company commitments to living wages in global supply chains. New Political Economy, 27(1), 99-115.

Margaret A. McLaren (2019) Global gender justice: human rights & political responsibility. Critical horizons 20(2), 127-144

Daniel Miller (2001) The poverty of morality. Journal of Consumer Culture, 1(2), 225–243.

Jan Nåls (2018) The difficulty of eliciting empathy in documentary. In Catalin Brylla & Mette Kramer (eds) Cognitive Theory and Documentary. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 135-148.

Kate Nash & John Corner (2016) Strategic impact documentary: contexts of production & social intervention. European journal of communication 31(3), 227–242

Tony Roberts & Chris Lunch (2015) Participatory video. In Robin Mansell and Peng Hwa Ang (eds) The International Encyclopedia of Digital Communication and Society. London: Wiley, 1-6.

Tillman Wagner, Richard Lutz & Barton Weitz (2009) Corporate hypocrisy: Overcoming the threat of inconsistent corporate social responsibility perceptions. Journal of Marketing 73(6), 77-91

Erik Olin Wright (2015) How to be an anticapitalist today. Jacobin, 12 February

Image credits

Conversation (https://thenounproject.com/icon/conversation-6769395/) by kliwir art from Noun Project (CC BY 3.0)

Blood, sweat & takeaways: credit BBC.

Girl model: credit Carnivalesque Films

UDITA: credit Rainbow Collective

Mangetout: credit BBC

SECTION: advice

Written by Sophie Burden, edited by Ian Cook (first published June 2025)

![]()