FEATURED EXAMPLES

Ilha das Fores

Girl model

Mangetout

Blood, sweat & takeaways

UDITA

Ghosts

Primark – on the rack

INGREDIENTS

INTENTIONS

Pop the bubble

Show capitalist evils

End violence & exploitation

TACTICS

Follow the people

Flip the script

Spend some time

Tell the truth

Show both sides

Make it funny

Workers take the mic

Juxtapose extremes

Hold ’em accountable

RESPONSES

These consumers are insane

I laughed my ass off

This is disgusting

Guilty as charged

I gotta do something

Silence your critics

IMPACTS

Corporations are punished

“Just showing up – again and again – can be the start of something.”

By Jock MacKinlay

IN BRIEF

Student Jock MacKinlay has taken the ‘Geographies of material culture’ module at the University of Exeter. He’s been watching trade justice documentaries, analysing the comments on their followthethings.com pages, and making sense of them using a draft copy of ‘The followthethings.com handbook for trade justice activism’. He knows a thing or two about how trade justice documentaries work and what they can do. He reflects on what he’s learned about how these films work and what they can do. He centres capitalism’s commodification of objects and people, how filmmakers and their subjects can turn grief into power, and how this work can gently and persuasively unravel the logic of global trade.

More about this page.

We are slowly piecing together a followthethings.com handbook for trade justice activism and are publishing draft pages here as we write them. This is an ‘advice’ page. The main text is an example of student work from the ‘Geographies of material culture’ module which followthethings.com CEO Ian ran at the University of Exeter in the 2024-25 academic year. Students watched 8 films, and read their pages on followthethings.com (with the expeption of an unfinished film called The ginger trail). They were asked to pair the comments brought together on each of the films’ followthethings.com pages with the appropriate ingredients phrases (naming their intentions, tactics, responses and impacts – show in bold below) being drafted for the Handbook. Using these phrases as a pattern language (see FAQs), students were tasked to work out how specific intentions (e.g. improve workers’ pay & conditions) needed specific tactics (e.g. flip the script) to generate different kinds of responses (e.g. this is disgusting), which could generate different kinds of impacts (e.g. audiences are empowered). [NB pages about each of these ingredients are coming soon] At the end of the module, students were asked to imagine that they had met someone who was about to make their first trade justice documentary. Drawing on what they had learned in the module, what advice could they give them on how to make it effective?

What makes a trade justice documentary effective isn’t just what it shows – it’s how it brings you into complicity. A tomato in Ilha das Flores. A child raising a Tesco flag in Mangetout. These aren’t just images. They’re arguments. And they don’t plead for change – they implicate. I’ve come to believe that the most powerful trade justice documentaries don’t persuade. They disrupt. They use irony, juxtaposition, grief, silence, repetition, and time to make global injustice unmissable – and unbearable.

Across this reflection, alongside learning from follow-the-things (2025) I draw on seven films from the module and analyse their techniques using ingredient phrases, emotional reactions, and viewer responses drawn from followthethings.com. I explore how films confront trade injustice – the structural exploitation baked into global supply chains that privilege profit and ownership over worker dignity (Chellan, 2023; Cook et al., 2002). Because if a documentary wants to challenge that system, it can’t just inform. It has to implicate. That’s the kind of effectiveness I’m tracing here

Commodification: objects and people

One way in which trade justice documentaries can be effective is by showing capitalist evils not through spectacle, but through logic – systems that make exploitation feel routine. Ilha das Flores made me laugh at first. The narration traced a tomato’s journey from plantation to middleman to supermarket shelf. It was absurd in its neatness – every movement tracked, measured, rationalised. But then came the landfill. The tomato was discarded, fed to a pig, and finally scavenged by children. By juxtaposing extremes, the film folds waste 🚮, animal 🐖, and human 🙋🏽 into the same supply chain. One viewer said: “I just felt like being sick… people who have to sift through garbage to find food” (Redroom Studios in Pavalow, 2025).🫣 I felt the same – but not because of the image. This is disgusting, I thought, because it felt so coldly logical – sicking not in tragedy, but routine.

Ryynänen et al. (2022) argue that disgust isn’t just emotional – it’s a moral alarm that ruptures what we accept as normal. This wasn’t an image designed to horrify. It became horrifying because I recognised it too late. Bloomfield and Sangalang (2014) describe juxtaposition as a “visual argument” – a structure that forces the viewer to connect what they’d rather keep apart. The film doesn’t explain the logic. It makes you feel it. Chellan (2023) helped me make sense of that discomfort: capitalism isn’t just cruel by accident. It’s a system that “privileges ownership over life.” Ilha das Flores doesn’t accuse. It implicates.

Girl Model continues this logic through quiet observation. Nadya, thirteen, is sized, and measured. There’s no voiceover. No commentary. Just a girl turned product. By following the people, the film shows how global capitalism doesn’t just move things – it moves bodies. “They are commodities. Easily replaceable” 😪 (Dowling in Hambly et al., 2025). I agreed – and that’s what disturbed me.😟 Wenzel (2011) calls this a “commodity biography”: a mapped transformation from subject to stock. I didn’t feel pity. I wasn’t the only one who felt guilty as charged, others agreed with me on followthethings.com “every person… [is] a collaborator or perpetrator of a… soul-sucking enterprise” (Anon, 2012e in Hambly et al., 2025). Not because I caused this – but because we all see models in every advert ever!!! Young (2003) calls this political responsibility: the moment you realise you’re inside the structure.

Whose pain are we watching?

If Section 1 left me wondering why I hadn’t noticed the violence sooner, these films show what happens when trade justice documentaries make that distance impossible to ignore – when they pop the bubble between comfort and consequence. In Mangetout, we begin at a Home Counties dinner party. Guests sip wine, eating mangetout, and debate “fairness” like it’s an abstract puzzle. Then, without warning, we cut to a Grannie, a Zimbabwean mangetout sorter discussing her suicide attempt. She’s calm. Precise. Not pleading – just speaking. By showing both sides, the film draws an initial equivalence between Global North opinion and Global South reality – but then cracks it open. One reviewer called it “the short and simple annals of the poor intercut with a champagne-fuelled dinner party” (Banks-Smith 1997 in Cook et al, 2025)

I agreed – but for me, it wasn’t just contrast. It was interruption. That’s what makes this technique effective – it shifts focus from guilt to voice. It asked who gets the last word. Cook et al. (2002) describe commodities as “economic DNA” – the buried trace of hands and histories. Mangetout doesn’t just reference that. It shows it. The peas aren’t just served. They’re stitched to lives. That’s what it means to pop the bubble: to let the dinner table speak back. Valenti (2020) warns that “balance” can become distortion when all voices aren’t equally free to speak. And by flipping the script, the film resists pity. The worker isn’t reduced to pain. Her voice carries its own narrative – one that didn’t need translation. Siddiqi (2009) calls this a refusal of “global moralism” – a rejection of pity and a reclamation of voice, where workers don’t need saving, just listening.

Blood, Sweat & Takeaways overwhelmed me in a different way. The British volunteers are exhausted. They break down in the factories. Cry into their hands. Scream at each other. These consumers are insane, I thought – not because they couldn’t cope, but because their breakdowns became the story. One reviewer nailed it: “ignorance and insouciance is the important flavour here… the BBC has carefully sifted all the good apples out to leave us only with the spoiled ones” (Sutcliffe 2009 in Clarke et al., 2025). Exactly. It didn’t feel like we were watching transformation. It felt like punishment – and the workers became props in that performance. Wood (2020) calls this “emotional optimisation”: where Western pain takes centre stage, and the system itself fades. It left me frustrated, not moved.

Grief into power

But not every film works through contrast. Some stay – showing what happens after the worst has already occurred. One way trade justice documentaries can be effective is by seeking to end violence and exploitation not through shock, but through duration – by staying with grief long enough for it to organise. In UDITA, we see two children walking through the wreckage of Rana Plaza. They see clothing in the rubble, labelled. Each tag still reads “Made in Bangladesh.” Later, their grandmother Razia stands among a crowd of women, fists raised, chanting for justice. One reviewer captured this transformation: “[Razia] now has to care for her daughter’s children… they walk over the rubble… each one has a Western label” (Anon 2015b in Barker et al., 2025). I kept noticing those labels. They weren’t just part of the debris – they were the thread connecting Razia’s grief to my comfort. That scene broke me 🫠😞- not because it was loud, but because it wasn’t. That’s what makes it effective: it invites presence, not pity.

That’s why this film works. It doesn’t just drop in to extract stories. It spends some time. Filmed over five years, UDITA captures the slow work of building trust – between filmmaker and subject, between worker and union. Robertson (2005) calls this “presence as method” – not just seeing, but staying. The camera doesn’t race. It follows Razia at a walking pace – into homes, into the streets, into grief. Evans (2020) describes this kind of duration as a way to break the “despondency trap”: when change feels impossible, just showing up – again and again – can be the start of something – exactly!!

Ghosts struck differently. The camera doesn’t narrate. It just watches Ai Qin, a real undocumented migrant worker, re-enact the moment of her survival. She stands on the roof of a white van as the tide rises, calling her son from the very bay where others drowned. I gotta do something, I thought. But it wasn’t guilt. It was something closer to reverence. “I won’t easily forget the shot of Ai Qin… [North Sea] waves about to engulf the van… making a final call to her son” (Sandhu 2007 in Allen et al, 2025). I couldn’t agree more – because it explained the scene, but because it admitted how unforgettable it was. That final call felt like it was for us. Richardson-Ngwenya and Richardson (2013) describe this as ethical representation: workers take the mic not through speech alone, but through presence. The silence becomes the point.

Unravel capitalism

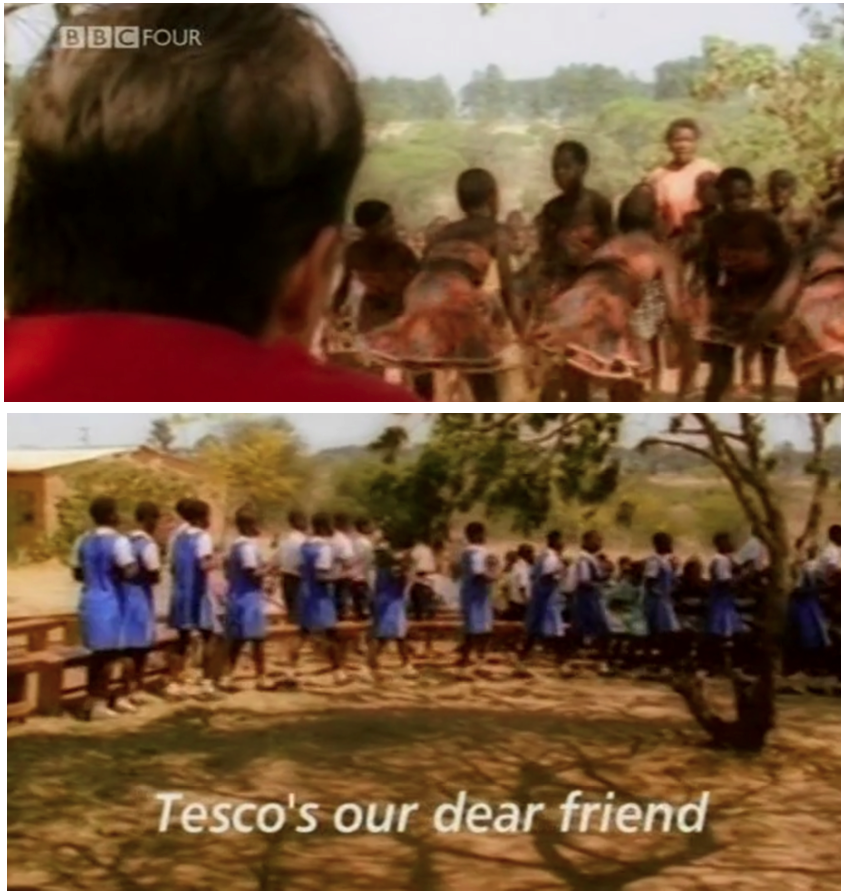

But grief doesn’t just stay personal. Some films turn their lens toward systems – and ask who gets to speak when the damage is done. Effective trade justice documentaries aim to hold corporations accountable ✊ – not just by criticising them, but by showing how they fall short of ethical practice. In Mangetout, there’s a scene that almost dares you to laugh: the Tesco flag being raised, while schoolchildren sing the Tesco song 🎶🎶🎶 “Tesco our dear friend” 🎶🎶🎶 and dance the Tesco dance. “It’s not just bizarre,” I remember thinking. “It’s dystopian.” 👽👽 One reviewer described it bluntly: “The Tesco flag was raised while children sang the Tesco song and danced the Tesco dance” (Holt 1997 in Cook et al., 2025). It’s funny until you realise the brand is being treated like a country – with rituals, pledges, even propaganda. The scene never tells us what to think. It just lets the lie speak.

That’s the tactic: tell the truth by letting performance unravel itself. Bartley & Child (2014) argue that when corporations become the subject of focused critique – especially ones wrapped in ethical branding – they’re vulnerable to targeted shaming. Mangetout never yells. It just watches. The effect is stronger than accusation. Cook et al. (2015) describe this kind of visual strategy as one that turns “spectacle into satire” – without needing to say a word. They make it funny. The scene made me flinch – Tesco, this is disgusting. Then I laughed my ass off. Then I felt guilty as charged. So effective – because it didn’t instruct. It implicated. It made me ask why this had ever felt normal.

Primark: On the Rack hits differently. It shows what happens when corporations don’t just deny wrongdoing – they try to silence their critics. In response to the BBC’s undercover footage surrounding child labourers, Primark didn’t quietly back away. They launched an aggressive counter-narrative. “Millions of people have been deceived by Panorama,” one spokesperson declared. “Teachers and pupils… have been badly let down” (Primark 2008 in Adley et al., 2025). That tone stuck with me – not because it was firm, but because it felt scolding. Like they weren’t responding to a crisis – just punishing someone for pointing it out. That’s what it means to silence your critics: not to rebut, but to erase. Cook et al. (2018) call this the “Streisand effect” – where trying to bury a critique only makes it louder. It backfired. Corporations are punished not always in court, but through public exposure. And the louder the denial, the more visible the problem becomes.

Concluding thoughts

What I’ve learned is that effective trade justice documentaries don’t just expose injustice – they make it undeniable. Not with guilt, but with structure. With editing, juxtaposition, silence, re-enactment, and time. The most effective films don’t preach – they disorient. They hold back. They let injustice implicate itself. When I first watched Ilha das Flores, I thought the image of a woman scavenging waste would shock me. It didn’t. The shock came from the voiceover — that cold, rational tracking of a tomato’s value. That was my first lesson: effective trade justice films don’t just show harm – they reveal the logic behind it.

That logic reappears across the films that stayed with me: a model commodified, a corporation mythologised, a migrant re-enacting her own pain. None of these scenes told me what to feel. They let the structure speak – and made me realise I was part of it. If I were to make a trade justice documentary now, I’d focus less on persuading, more on positioning. I’d start with the worker. I’d spend time. I’d resist neat conclusions. Because effectiveness isn’t clarity – it’s complexity.

That’s what these films offered me: not closure, but craft. Not answers, but better questions. And a deeper understanding of how form can confront power – and why it must.

SOURCES

Adley, K., Keeble, R., Russell, P., Stenholm, N., Strang, W. and Valo, T. (2025) Primark – on the rack. (http://followthethings.com/primark-on-the-rack.shtml last accessed May 14th 2025)

Allen, H., Heaume, E., Heeley, L., Hedger, R., Johnson, S., McGregor, O. and Webber, L. (2025) Ghosts. (http://followthethings.com/ghosts.shtml last accessed May 14th 2025)

Barker, T., Collier, J., Baker, A., Coppen, L. and Eve, H. (2025) UDITA (ARISE). (http://followthethings.com/udita.shtml last accessed May 14th 2025)

Bartley, T. & Child, C. (2014) Shaming the corporation: the social production of targets and the anti-sweatshop movement. American Sociological Review 79(4), p.653–679

+18 sources

Bloomfield, E. F. & Sangalang, A. (2014) Juxtaposition as visual argument: health rhetoric in Super Size Me and Fat Head. Argumentation and Advocacy 50(3), p.141–156.

Chellan, N. (2023). The life of capitalism. in his F/Ailing capitalism and the challenge of COVID-19. Leiden: Brill, p.180-216

Clarke, H., Thomson, B., Bartley, V., Ibbetson-Price, K., Christie-Miller, E. and Schofield, H. (2025) Blood, Sweat & Takeaways. (http://followthethings.com/blood-sweat-takeaways.shtml last accessed May 14th 2025)

Cook, I. et al., 2018. Inviting construction: Primark, Rana Plaza and political LEGO. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 43(3), p.477–495

Cook et al, I. (2025) Mangetout. (http://followthethings.com/mange-tout.shtml last accessed May 14th 2025)

Cook et al, I. (2002) Commodities: The DNA of capitalism. (https://followtheblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/commodities last accessed May 14th 2025)

Cook, R.F., Vos, T.P., Prager, B. & Hearne, J. (2015) Journalism, politics and contemporarydocumentaries: a ‘Based on a True Story’ dossier. Visual Communication Quarterly 22(1), p.15–33

Evans, A., 2020. Overcoming the global despondency trap: strengthening corporate accountability in supply chains. Review of International Political Economy 27(3), p.658–685

Hambly, A., King, E., Keogh, A., Renny-Smith, C., Callow, E., Thorogood, J. & Alloy, V. (2025) Girl Model: The Truth Behind The Glamour. (http://followthethings.com/girl-model.shtml last accessed May 14th 2025)

Pavalow, M. (2025) Ilha das Flores. (http://followthethings.com/ilhadasflores.html last accessed May 14th 2025)

Richardson-Ngwenya, P. & Richardson, B. (2013) Documentary film and ethical foodscapes: three takes on Caribbean sugar. Cultural Geographies 20(3), p.339–356.

Robertson, R. (2005) Seeing is believing: an ethnographer’s encounter with television documentary. in A. Grimshaw & A. Ravetz (eds) Visualizing anthropology. Bristol: Intellect Books, p.42–54

Ryynänen, M., Kosonen, H. & Ylönen, S. (2023) From visceral to the aesthetic: tracing disgust in contemporary culture. in their (eds.) Cultural Approaches to Disgust and the Visceral. London: Routledge, p.3-16

Siddiqi, D.M. (2009) Do Bangladeshi factory workers need saving? Sisterhood in the post-sweatshop era? Feminist Review 91(1), p.154–174

Valenti, J.M. (2020) When environmental documentary films are journalism. in Sachsman D. & Valenti, J.M. (eds) Routledge handbook of environmental journalism. London: Routledge, p.99-112

Wenzel, J. (2011) Consumption for the common good? Commodity biography film in an age of postconsumerism. Public Culture 23(3), p.573–602

Wood, R., (2020) ‘What I’m not gonna buy’: Algorithmic culture jamming and anti-consumer politics on YouTube. New Media & Society 23(9), p.2754–2772

Young, I.M. (2003) From guilt to solidarity: sweatshops & political responsibility. Dissent 50(2), 39-44

Image credits

Conversation (https://thenounproject.com/icon/conversation-6769395/) by kliwir art from Noun Project (CC BY 3.0)

Ilha das Flores: credit Casa de Cinema de Porto Alegre

Girl model: credit Carnivalesque Films

Mangetout: credit BBC

Blood, sweat & takeaways: credit BBC

UDITA: credit Rainbow Collective

Ghosts: credit Beyond Films

Primark – on the rack: credit BBC

SECTION: advice

Written by Jock MacKinlay, edited by Ian Cook (first published June 2025)

![]()