FEATURED EXAMPLES

Primark – on the rack

Mangetout

Ilha das Flores

Blood, sweat & takeaways

Girl model

Ghosts

UDITA

INGREDIENTS

INTENTIONS

Reach new audiences

Pop the bubble

Change consumer behaviour

Change corporate behaviour

Improve pay and conditions

Show what’s possible

TACTICS

Hold ’em accountable

Blame, shame & guilt

Lie to tell the truth

Start somewhere different

Involve consumers

Humanise workers

Find the unions

Find a character

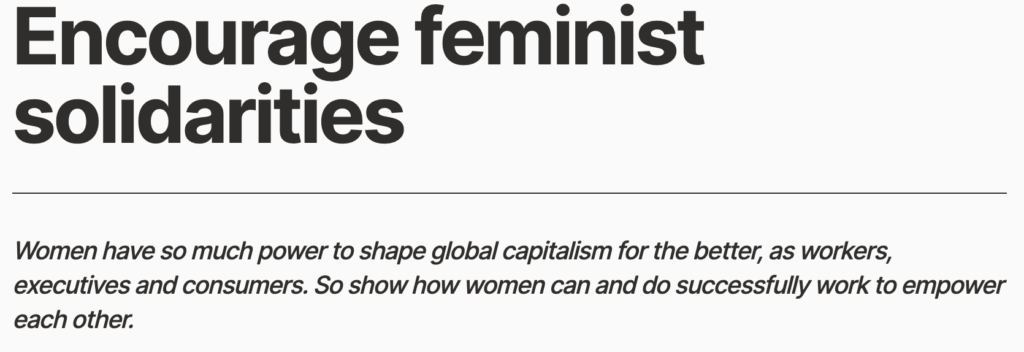

Give workers the mic!

Encourage empathy

Juxtapose extremes

Suggest concrete action

Encourage feminist solidarities

RESPONSES

Attack your critics

Liar! Fraud!

Wow 💥 WTF?

I’m so angry

This is disgusting

Guilty as charged

I just cried

I gotta do something

Who’s responsible?

These people are inspiring

IMPACTS

Now we’re talking

Corporations change

I shop differently now

Workers suffer

Activism is inspired

Debts are paid off

Workers’ pay & conditions improve

“Get people to reflect, not recoil“

By Abbie Gollings

IN BRIEF

Student Abbie Gollings has taken the ‘Geographies of material culture’ module at the University of Exeter. She’s been watching trade justice documentaries, analysing the comments on their followthethings.com pages, and making sense of them using a draft copy of ‘The followthethings.com handbook for trade justice activism’. She knows a thing or two about how trade justice documentaries work and what they can do. She’s been asked to imagine meeting a filmmaker who’s planning a new trade justice documentary. What advice could she give? Consider the emotions your work could evoke in its audiences. Which ones will encourage them to act in ways that could improve workers’ pay and conditions? And maybe start with the workers first? What’s her theory of change? What activism are they involved in. How could a filmmaker help?

More about this page.

We are slowly piecing together a followthethings.com handbook for trade justice activism and are publishing draft pages here as we write them. This is an ‘advice’ page. The main text is an example of student work from the ‘Geographies of material culture’ module which followthethings.com CEO Ian ran at the University of Exeter in the 2024-25 academic year. Students watched 8 films, and read their pages on followthethings.com (with the expeption of an unfinished film called The ginger trail). They were asked to pair the comments brought together on each of the films’ followthethings.com pages with the appropriate ingredients phrases (naming their intentions, tactics, responses and impacts – show in bold below) being drafted for the Handbook. Using these phrases as a pattern language (see FAQs), students were tasked to work out how specific intentions (e.g. improve workers’ pay & conditions) needed specific tactics (e.g. flip the script) to generate different kinds of responses (e.g. this is disgusting), which could generate different kinds of impacts (e.g. audiences are empowered). [NB pages about each of these ingredients are coming soon] At the end of the module, students were asked to imagine that they had met someone who was about to make their first trade justice documentary. Drawing on what they had learned in the module, what advice could they give them on how to make it effective?

Question

How can I make an effective trade justice documentary?

Answer

‘Effective’ means many things: matching impacts to intentions, getting people talking. But you can do more. Effective documentaries can lead to action; the ultimate goal: improve workers’ pay and conditions. I assume this is your aim. But not just as a temporary ‘lifeboat’ (Kister and Wenner, 2024) – you want long-lasting change. I’ve watched some trade justice films. Some missed this mark. But they all point towards it. You can learn from them.

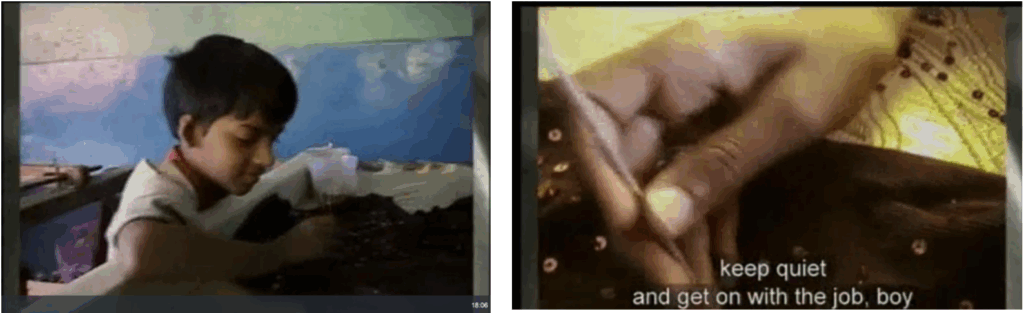

Start ambitious. Change corporate behaviour. Expose how they exploit workers, shame them into action. Corporations can change structurally – improve pay and conditions! This is what Primark on the Rack attempted. Posing as buyers, narrator McDougall’s team went to hold Primark accountable for ‘its illegal labour activities’ (Maroney; 190-1; in Adley et al., 2025), capturing footage of young boy Mantheesh working illegally on Primark garments in India. This scene caused outrage. Primark became the ‘poster boy’ for child labour (Cook et al., 2018; 483, in Adley et al., 2025) 😬

Primark caught? Nope! They fired back. Attacked their critics. ‘Liar! Fraud! The footage is fake!’ I didn’t know who to believe. Commenters argued over who’s right. This pivotal scene of Mantheesh became about everything but his struggles. Backfire! Panicking, Primark abruptly closed the three factories blamed of outsourcing and child labour. Rid themselves of the problem, leaving ‘hundreds of garment workers in an even worse position than before’ (Arnott; 36; in Adley et al., 2025). Workers suffer.

Thanks to the film, ”good days’ for Mantheesh have come to an abrupt end’ (Hunt; 22, in Adley et al., 2025). 😳 . This is the opposite of its intention. I’ve used this example to show you how impactful film can be – and how risky. DON’T lie to tell the truth. Workers might suffer.

SO.. let’s start smaller – a different angle. Target consumers. Try to change consumer behaviour. If you want people to rethink where their stuff comes from, pop the bubble. All activists need to shine light on the hidden realities (Duncombe, 2012). Cook and Woodyer (2012) explain how the ‘fetish’ of commodities hides the hands making them. So, as Boyd says (2012; in Duncombe, 2016, 122), you must make ‘the invisible visible.’ Showing the workers juxtaposing extremes can do this – it gets people questioning without blame, shame or guilt – which clearly didn’t work for Primark on the Rack.

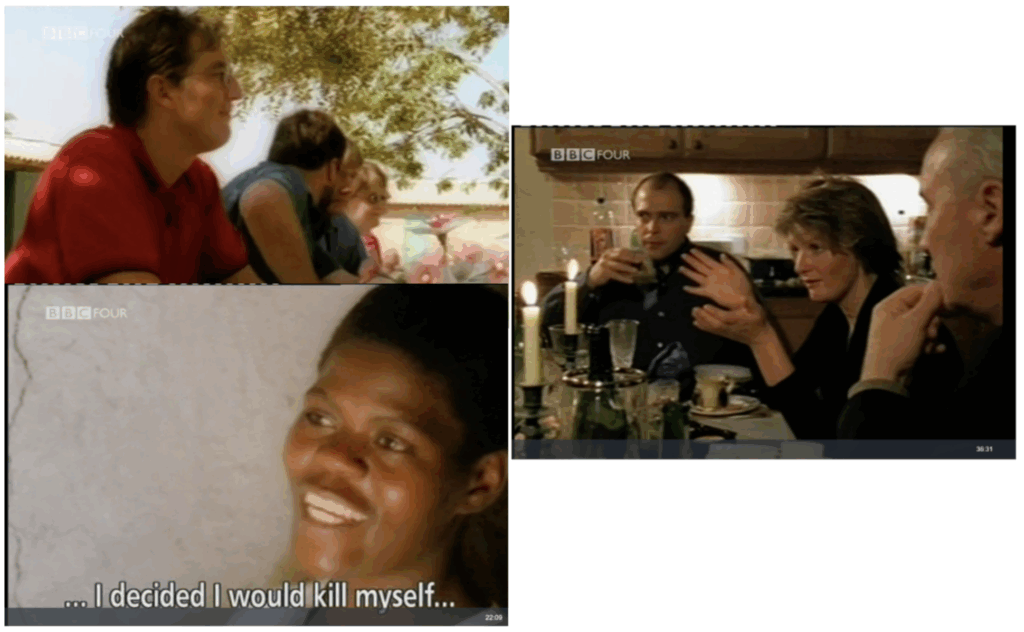

Mangetout and Ilha das Flores did this. But you can’t just throw any scenes together.Bloomfield and Sangalang (2014) helped me get this – you’ve gotta show the relationship between the scenes, like cause and effect, or moral contrast – so people connect the dots themselves. Leave space for imagination (Cook et al., 2007; 118). Like how Mangetout juxtaposes middle class diners who ate mangetout ‘between outbursts of smug crassness, [as] the African pickers were being treated as slaves’ (Holt, p.5; in Cook et al., 2025). Meanwhile Mark Dady, Tesco manager, smiles over his workers. It showed how Tesco policy exploits workers who completely rely on them, ignorant of their struggles, giving more attention to the vegetable than those producing it. Tesco weren’t explicitly blamed – viewers drew ‘their own depressing conclusions’ (Truss, np, in Cook et al., 2025) about how the workers were treated. I was so angry!

Ilha das Flores also juxtaposed extremes showing the tomato-connected lives of workers, animals, and consumers. For some, it hit hard – ‘impossible not to shed tears while watching’ (Anon; 17; in Pavalow, 2025). Wow 💥 WTF? I was shocked seeing dead bodies, children eating scraps a family had previously deemed inedible. But the shock didn’t lead me anywhere. If you look at Chouliaraki (2010), she explains this problem. She says when films show suffering too graphically or abstractly, they risk fetishising all over again. It becomes a spectacle of disgust (Lissner, 1981; 32, in Chouliaraki, 2010). I felt bombarded.

So, same technique, totally different outcomes. Emotions can work against you ⚠️ . Ilha das Flores left people feeling disgusted – by the end ‘I just felt like being sick’ (Redroom Studios, np; cited in Pavalow, 2025). Disgust can make your audience recoil (Ryynänen, Kosonen, and Ylönen, 2023). Someone said ‘the holocaust images made me stop watching’ (@andrewsharpe2587, np, in Pavalow, 2025). Not exactly the spark you need to fuel activism.

But anger you can work with! Anger at Mangetout’s revelations inspired activism. Read Micheletti and Stolle (2008, p.749) to understand this emotional mobilisation. They explain how strong emotions like anger can drive change consumer behaviour and change corporate behaviour. That’s an effective outcome! Unlike disgust, anger is intentional (Ryynänen, Kosonen, and Ylönen, 2023). Mangetout was effective because, as Brown and Pickerill (2009) explain, there was somewhere to aim it: Tesco. Tesco felt pressured to join the Ethical Trading Initiative. Corporations have changed! SUCCESS!! 🎯 You see there are different ways to apply pressure. Different emotions get different responses. Get people to reflect, not recoil.

Targeting consumer audiences seems to be effective – you can target them other ways! Try to change consumer behaviour. Kahn (2016) explains that consumers are more responsible than ever – the solution to fast fashion problems! Make them feel they gotta do something.

Involving consumers can be a powerful way to show them how to change. Blood Sweat and Takeaways tried this by taking 6 British food lovers to ‘walk-a-mile’ in workers’ shoes in Thailand and Indonesia (Cuthbertson; 46; in Clarke et al., 2025). Millions watched – it reached new audiences and opened viewers’ eyes: ‘I never gave much thought to where my food comes from’ (Lynn, np, in Clarke et al, 2025). But the show failed to tell viewers how to help – ‘boycott tuna or buy more of it?’ (Sutcliffe 2009 np, in Clarke et al., 2025).

🤔 What was the point? Instead, it focused on participants’ personal journeys, like Manos’ emotional revelation and apology to the workers shown below. It didn’t push for social change (Gupta and Fawcett, np, in Clarke et al., 2025), and letting consumers ‘play at’ being workers only extended the gap between ‘us’ and ‘them’ (Yang, 2017; 61).

You must TELL consumers what to do (Haug and Busch, 2016). Explicitly link consumer habits with workers’ lives. In Primark on the Rack, a young woman is shown video evidence of children working on a top from Primark that she owned. She was shocked! Guilty as charged! Trust in Primark – gone. ‘It’s the end of the affair’ says McDougall (Panorama, 2008; 48:43). Consumer behaviour changed 👍 . people said they’d shop differently now 👍 . Did they?

I felt guilty too. All those times I’ve ventured to Primark for another cheap top. But what about the factory owners I’d seen? The children’s parents? Who’s responsible? I started justifying my actions, I’m a student. I can’t afford to shop elsewhere. ‘How dare that reporter incline towards that woman [shopping] in anyway that it’s her fault for buying clothes from Primark’ (Maddox 2008 np; in Adley, 2025). Young (2003) explains this response. Guilt is backwards-looking, people get defensive (Bartky 2002; in Yang 2017) and angry. Instead of collective action, blaming a consumer caused resentment and refusal to take responsibility (Young, 2003). I came to a dead end. But then I returned to Young (2003). She says you want to show people that it’s everyone’s responsibility.Y ou need to show them how to make a difference, but don’t blame. Guilt isn’t always effective.

So avoid responses that will backfire. Your doc could be more effective by humanising workers. Get people talking about them. You’ve learnt about emotional responses – which ones should you evoke? Here you could turn to Kemp (2025) who explains that empathy can motivate helping behaviour and catalyse action (Nash and Corner, 2016). You want action! So encourage empathy.

The unintentional popularity of Girl Model shows that finding a character can really effectively connect an audience to workers struggles through empathy. ‘It became ‘essential viewing for adolescent girls’ (Burr, 2012, np; in Hambly et al., 2025) because people had been emotionally impacted. Aspiring model Nadya (13) is carted off to Tokyo with hope for a better life, and money for her family. But these promises dissolve and the glamour and gloss of the industry was stripped away (Kermode, 2012, np, in Hambly et al., 2025). The images show her real emotions under the fake glamour. I just cried ‘I wanted to give Nadya a hug, because I felt her pain’ (DisturbedPixie, np; in Hambly et al, 2025).

The rawness of disappointment touched a nerve. Canning and Reinsborough (2012) explain that your audience cares more when they relate. So you could include relatable characters to engage your audience. Point your camera towards the workers and it becomes an ‘empathy machine’ (Jackson in Nals, 2018; 135). But there was nothing I could for Nadya. I was invested but at a dead end. But Ghosts shows how empathy CAN effectively inspire action.

Ghosts finds a character: Ai Qin. We follow her closely as she migrates to the UK for better wages and work. But she becomes trapped in a modern slave system. She repeatedly suffers. She cries and then… I cried.

My emotions mirrored hers (Nals, 2018). Her plight comes up to you like an unforgiving tide (Keak np; in Allen et al., 2025). You want to help her. Some viewers said that showing her ordinary emotions brought her closer to ‘us’ bridging a ‘gulf’ between viewer and subject (Brass; 346; in Allen et al., 2025), but I felt like I was framed in an oppressor vs oppressed dynamic (Bardan, date; in Pereen, 2014; 44). She was a victim, the audience are saviours (Pereen, 2014; 44). Ghosts ends with the Morecambe Bay tragedy: Ai Qin survives, but viewers learn the victims’ families struggle with debt. Broomfield established the Morecombe Bay Victim’s fund (O’Keeffe 2006; in Allen et al., 2025) and emotionally-connected viewers, now cast as saviours, donate to clear these debts. Debts are paid off.

So if you encourage empathy and suggest concrete action you can drive effective change. But this help was temporary. And empathy donation relationships rely on the colonial gaze being maintained (Hall, 1992; in Chouliaraki, 2010) which is part of the problem. Your film can use empathy to get immediate change, but you need to switch it up to improve workers pay and conditions long-term.

Individualising and blaming consumers and corporations can undermine your goal. An effective doc must promote trade justice without endangering workers. So start somewhere different. Let workers take the mic. Like UDITA (Arise) did. Following 5 female union workers, it shows what’s possible: powerful, collective action – ‘women’s hope and commitment to create better conditions for the next generation’ (Spooner; 32, in Barker et al, 2025). These people are inspiring. Empowered workers showed how resistance is already improving pay and conditions (Siddiqi, 2019). They had a voice – and knowing best how the garment industry should change (Khan, 2016), they can tell us what they want – (O’Neill, np; in Barker et al, 2025).

I could no longer excuse ignoring how my t-shirts are made because ‘[T]he actual garment workers themselves are saying that they want us to shop consciously. WE CAN DO IT’ (Gregory, np, in Barker et al., 2025). It shows that the workers don’t need ‘saving’ – Primark – On the Rack showed how victimising workers can harm their interests (Siddiqi, 2019), moving beyond the ‘us’ and ‘them’ divide. Before, I was encouraged to be a guilty consumer . Now I was encouraged to be a feminist in solidarity – an important move for audiences to make because it shows the collective responsibility we all have – that workers need to resist too (Young, 2003; 42).

After so much despair, witnessing their resilience gave me hope. Your film can help apply pressure in the right places. Find the unions and help them to improve pay and conditions. Inspire viewers to work collectively. Make it forward-looking (Robin Zheng, 2019). Show there is an alternative, and you will make real change.

So to improve pay and conditions: target consumers and corporations, but be cautious ⚠️ . Get people talking about the workers, and mobilise emotions like empathy and anger into concrete action. Collate these ideas – have a theory of change and apply pressure from different angles. Like UDITA, give workers opportunity to show what’s possible to give the audience hope, a sense of togetherness.

SOURCES

Adley, K., Keeble, R., Russell, P. Stenholm, N, Strang, W, and Valo,. T (2025) Primark – on the rack. followthethings.com/primark-on-the-rack.shtml (last accessed: 28th April, 2025)

Allen, H, Heaume, E, Heeley, L. Hedger, R, Johnson, S, McGregor, O & Webber, L (2025) Ghosts. followthethings.com/ghosts.shtml (last accessed: 25th April 2025)

Barker, T, Collier, T, Baker, A, Coppen, L & Eve, H (2025) UDITA (ARISE). followthethings.com/udita.shtml (last accessed: 25th April, 2025)

Bloomfield, E.F. and Sangalang, A. (2014) Juxtaposition as Visual Argument: Health Rhetoric in Super Size Me and Fat Head. Argumentation and Advocacy, 50(3), pp. 141– 156

+25 sources

Brown, G. and Pickerill, J. (2009) Space for Emotion in the Spaces Of Activism. Emotion, space and society, 2(1), pp. 24–35

Canning, D. and Reinsborough, P. (2012) Lead With Sympathetic Characters. in Beautiful Trouble. OR Books, p. 146

Chouliaraki, L. (2010) Post-humanitarianism: Humanitarian Communication Beyond a Politics of Pity. International journal of cultural studies, 13(2), p. 107–126.

Clarke, M Thomson, B. Bartley, V. Ibbetson-Price, K. Christie-Miller. E. & Schofield, H. (2025) Blood, Sweat & Takeaways. followthethings.com/blood-sweat-takeaways.shtml (last accessed: 28th April, 2025)

Cook, I. and Woodyer, T. (2012) Lives of Things. in The Wiley‐Blackwell Companion to Economic Geography. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, p. 226–241

Cook, I. et al. (2007) ‘It’s More Than Just What It Is’: Defetishising Commodities, Expanding Fields, Mobilising Change. Geoforum, 38(6), p. 1113–1126

Cook, I, et al., (2025) Mangetout. followthethings.com/mange-tout.shtml (last accessed: 28th April, 2025)

Duncombe, S. (2012) It Stands On Its Head: Commodity Fetishism, Consumer Activism, And The Strategic Use Of Fantasy. Culture and organization, 18(5), p.359–375.

Duncombe, S. (2016) ‘Does It Work? The Æffect of Activist Art. Social research 83(1), p.115-134.

Duncombe, S. (2023) A Theory of Change for Artistic Activism. The Journal of aesthetics and art criticism, 81(2), pp. 260–268

Hambly, A, King, E, Keogh, A, Renny-Smith, C, Callow,E, Thorogood, J & Alloy, V (2025) Girl Model: The Truth Behind The Glamour. followthethings.com/girl-model.shtml (last accessed: 28th April, 2025)

Haug, A. and Busch, J. (2016) Towards an Ethical Fashion Framework. Fashion theory 20(3), p.317–339

Pavalow., M (2025) Ilha das Flores. followthethings.com/ilhadasflores.html (last accessed: 28th April, 2025)

Kemp, D. (2025) Comparing Disgust and Sadness: Examining the Interaction of Emotion and Information in Charity Appeals. Journal of social marketing, 15(1), p.42–58.

Khan, R. (2016) Doing Good and Looking good: Women in ‘Fast Fashion’ Activism. Women & Environments International Magazine, 96/97, p.7-9

Kister, J. and Wenner, M. (2024) Living Wages as Life Boat to Rescue Fairtrade’s Values for Hired Labour? The Case of Indian Tea Plantations. Die Erde: journal of the Geographical Society of Berlin 154(3), p.80-94

Micheletti, M. and Stolle, D. (2008) Fashioning Social Justice Through Political Consumerism, Capitalism, And The Internet. Cultural studies 22(5), p.749–769

Nåls, J. (2018) The Difficulty of Eliciting Empathy in Documentary. in Brylla, C & Kramer, M. (eds) Cognitive Theory and Documentary. Oxford: Palgrave Macmillan, p.135-148

Nash, K. and Corner, J. (2016) Strategic Impact Documentary: Contexts Of Production And Social Intervention. European journal of communication 31(3), p.227–242

Peeren, E. (2014) The Spectral Metaphor: Living Ghosts and the Agency of Invisibility. London: Palgrave Macmillan

Ryynänen, M., Kosonen, H.S. and Ylönen, S.C. (2023) From visceral to the aesthetic: tracing disgust in contemporary culture. in their (eds.) Cultural Approaches to Disgust and the Visceral. London: Routledge, p.3-16

Siddiqi, D.M. (2009) Do Bangladeshi Factory Workers Need Saving? Sisterhood In The Post-Sweatshop Era. Feminist review, 91(91), p.154–174

Yang, J. (2017) Screening privilege: global injustice & responsibility in 21st-Century Scandinavian film & media. PhD thesis: University of Oslo (https://www.duo.uio.no/bitstream/handle/10852/70905/Yang%2bPhD%2bScreening%2bPrivilege.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y last accessed 28th April 2025)

Young, I. (2003) From guilt to solidarity: sweatshops & political responsibility. Dissent 50(2), p.39-44

Zheng, R. (2019) What Kind of Responsibility Do We Have for Fighting Injustice? A Moral- Theoretic Perspective on the Social Connections Model. Critical horizons : journal of social & critical theory, 20(2), p.109–126

Image credits

Icon: conversation (https://thenounproject.com/icon/conversation-6769395/) by kliwir art from Noun Project (CC BY 3.0)

Primark on the rack: credit BBC.

Mangetout: credit BBC

Ilha das Flores: credit Casa de Cinema de Porto Alegre

Blood, sweat & takeaways: credit BBC

Girl model: credit Carnivalesque Films

Ghosts: credit Beyond Films

UDITA – credit Rainbow Collective

Handbook screengrabs: credit followthethings.com

SECTION: advice

Written by Abbie Gollings, edited by Ian Cook (first published July 2025)

![]()