FEATURED EXAMPLES

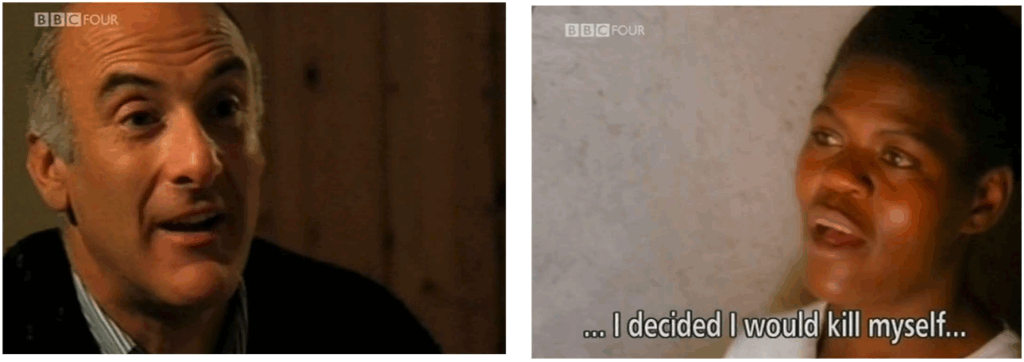

Girl model

Mangetout

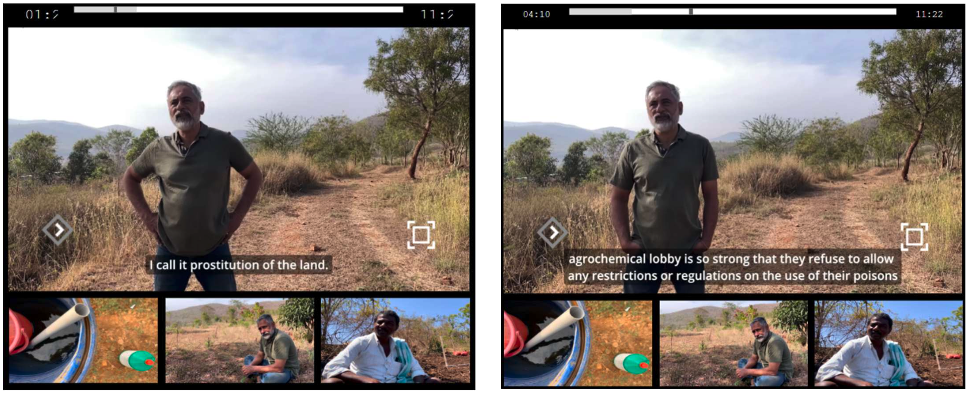

The ginger trail

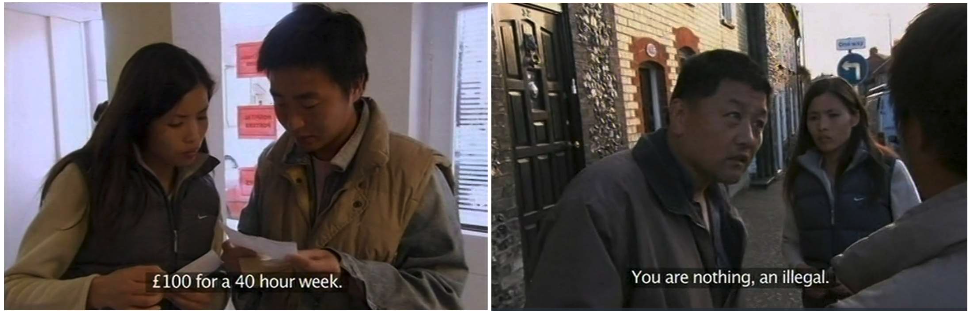

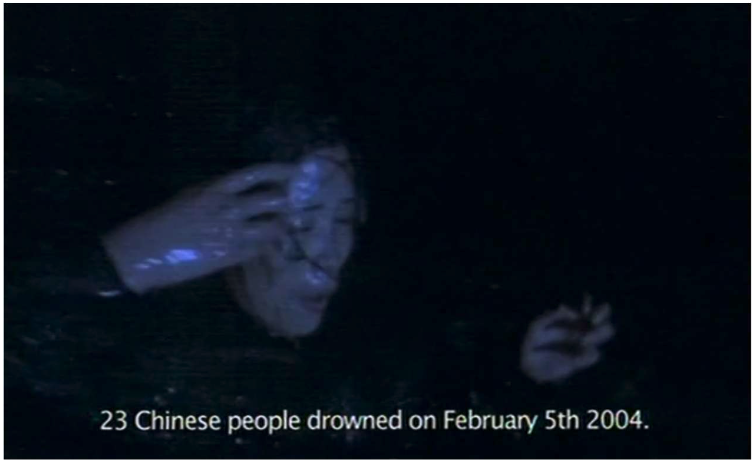

Ghosts

Primark – on the rack

INGREDIENTS

INTENTIONS

Pop the bubble

Cross cultures

Tell the truth

Show capitalist evils

End violence & exploitation

Change corporate behaviour

Teach economic geography

TACTICS

Have a theory of change

Target the right brand

Follow the thing

Tell the truth

Tell a story

Include emotion

Encourage empathy

Find & give inspiration

Workers take the mic!

Find a character

Create a character

Bring managers into view

Show the violence

Include suffering kids

Juxtapose extremes

Blame, shame & guilt

Encourage feminist solidarities

Add mood music

Silence your critics

RESPONSES

This is so sad

This is disgusting

I’m so angry

I just cried

These consumers are insane

Capitalism is sh*t

These people are inspiring

This gives me hope

I want to find out more

IMPACTS

Now I know!

Now we’re talking

Activism is publicised

Activism is inspired

Debts are paid off

Governments intervene

Corporations change

“Choose the emotion that won’t let go – then hit ‘record’“

By Luke Elkington

IN BRIEF

Student Luke Elkington has taken the ‘Geographies of material culture’ module at the University of Exeter. He’s been watching trade justice documentaries, analysing the comments on their followthethings.com pages, and making sense of them using a draft copy of ‘The followthethings.com handbook for trade justice activism’. He knows a thing or two about how trade justice documentaries work and what they can do. He’s been asked to imagine meeting a filmmaker who’s planning a new trade justice documentary. What advice could he give? Get inspired by the films he’s watched, and get the emotions right. Then record.

More about this page.

We are slowly piecing together a followthethings.com handbook for trade justice activism and are publishing draft pages here as we write them. This is an ‘advice’ page. The main text is an example of student work from the ‘Geographies of material culture’ module which followthethings.com CEO Ian ran at the University of Exeter in the 2024-25 academic year. Students watched 8 films, and read their pages on followthethings.com (with the expeption of an unfinished film called The ginger trail). They were asked to pair the comments brought together on each of the films’ followthethings.com pages with the appropriate ingredients phrases (naming their intentions, tactics, responses and impacts – show in bold below) being drafted for the Handbook. Using these phrases as a pattern language (see FAQs), students were tasked to work out how specific intentions (e.g. improve workers’ pay & conditions) needed specific tactics (e.g. flip the script) to generate different kinds of responses (e.g. this is disgusting), which could generate different kinds of impacts (e.g. audiences are empowered). [NB pages about each of these ingredients are coming soon] At the end of the module, students were asked to imagine that they had met someone who was about to make their first trade justice documentary. Drawing on what they had learned in the module, what advice could they give them on how to make it effective?

Question

How can I make an effective trade justice documentary?

Answer

First things first, cos you’re making a trade justice documentary, your film must contribute to the Trade Justice Movement – or TJM. But what does that even mean?!?!? The TJM challenges unfair imbalances in power between trading nations by tearing up the rule book ✊🏽 and the goal is to create a global system which prioritizes the people 👩🏻🤝👩🏾 and the planet 🌍 (Bannister & Bergan, 2023). So, to be a trade justice documentary, your activism must try to shift power away from the capitalist class 👿 and toward supply chain workers 🤗 (Wright, 2015). Easy right ?

Now, for your film to be effective, its intentions must lead to real-world impact. To generate the greatest impact, I suggest having a theory of change 🤔 AKA a strategy to maximize your film’s effectiveness. This will help you focus on a specific TJM issue to create meaningful and targeted 🎯 change (Duncombe, 2023)!!!

OK … let me tell you a story. It’s 2008. I’m watching ⚽️ football. Age 6. Suddenly, it’s half-time. A charity’s plea for donations appears on the TV. Starving Sudanese children 👶🏿 scatter the screen. Their exposed black ribs protrude from the telly stabbing 🗡 into my young eyes – bringing them to tears 😢. WHY do I still remember? Emotions imprint far deeper than facts ever can – so your film must aim not just to inform, but to include emotion that will shake your viewer.

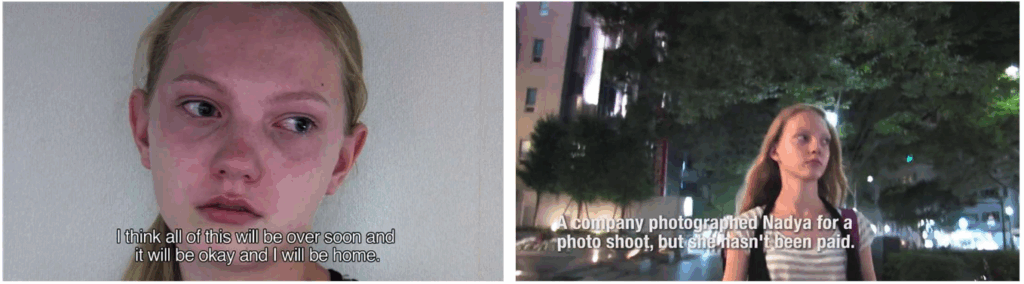

In April, I walked past Primark. My attention focused on glossy posters of young girls 👧 posing. Slowly, their faces distorted into Nadya Vall from Girl Model. Filmmakers follow this 13 year old girl from Siberia to Tokyo, chasing her dream to become a model. But it falls apart and she cries for help. The image burnt 🔥 into my brain 🧠. I couldn’t stop thinking about Nadya.

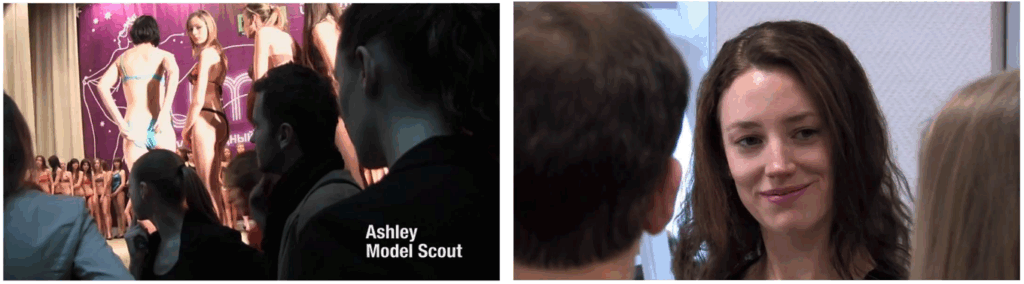

Filmmakers use tactics to trigger 🤮 😭 😢 😫 😡 😳 😊. Girl Model finds a character in Nadya who ‘gives the film a clear protagonist'(Saito in Hambly et al., 2025, np) creating a bond between the viewer and Nadya (Nash & Corner, 2016). The film includes suffering kids 👧 as Nadya cries to return to her impoverished home which is contrasted with Ashley, Nadya’s manager, who is free to wander her ‘cavernous Connecticut mansion’ 🏡 (Lucca in Hambly et al., 2025, np).

By bringing a manager into view, filmmakers reveal Ashley’s apathy through unsettling imagery – strange dolls 🪆and eerie photo cut-outs of models – which underscore her ‘disconnection from the modelling world’ (Redmon in ibid) and Nadya (Natter & Jones III, 1993). These tactics together encourage empathy 🥹by helping viewers really understand Nadya’s suffering → which often makes viewers sad (Redmon in Hambly et al., 2025; Dant, 2012).

It worked! It’s ‘saddening’ ☹️ (Almachar in Hambly et al., 2025, np). I’m so sad. Sadness is ‘a response to and feeling of loss’ (Kemp, 2025, p.44). Myself and others found Girl Model pretty ‘disturbing’ (Cli in Hambly et al., 2025, np)….it’s disgusting 🤮 . These feelings are brought on by violations of morality and with these physical feelings of revulsion 🤢, the film’s message hits deeper into the viewer’s heart ❤️ (Ryynänen et al., 2023).

By not ramming information down our throats, Girl Model told the truth – ‘a verité narrative’ (Sabin & Redmond in Hambly et al., 2025, np) and this amplified 🔊 the film’s impacts ☹️ 🤮 (Sabin & Redmond in Hambly et al., 2025).

Activism was inspired! Someone else made a film, people asked how they could create change, and conversations roared online – this engagement with the film is the first step toward real change … now we’re talking 💬 (Sabin & Redmond and Bleasdale in Hambly et al, 2025).

So now we know about Nadya’s exploitation…. our knowledge is the starting point for action ✊🏽.

Hold on ⛔️. Wenzel (2011) warns that consumers often confuse gaining knowledge with meaningful action. As a result, films can end up re-fetishizing commodities, simply generating new demand: dammit 😤 (ibid).

BUT WAIT! Nash and Corner (2016) explain how to overcome this…..emotions can be just as powerful, if not more so, than knowledge. By fostering emotional attachment to an issue, films have the potential to stimulate genuine action, not just passive awareness (ibid)!!!!

OK, now I know emotions are important. Girl Model got people ☹️ and 🤮. Mangetout got people 😡.

Mangetout popped the bubble by confronting Brits ‘with their most popular supermarket Tesco actually running a farm in Zimbabwe’ (Miller in Cook et al., 2025, np). Crossing cultures and following the thing traces the journey of mangetout peas 🫛 ‘from African soil to English dinner plate’ (Phillips in ibid) exposing the interconnected web of commodities and their externalities along the way (Callon, 1998). BAM 💥 my commodity fetishism 🫧 was popped ← Marx can #RIP 🪦 (Cook et al., 2002).

Tesco veg buyer Mark Dady travels to Zimbabwe bringing managers into view. He inspects Chiparawe farm [code 🧑💻 for] he bullies farmers to grow the perfect 🫛 for minimal Ps 💷 (Aaronovitch in Cook et al., 2025). Mark’s arrival 🛬 is accompanied by imperial music to add mood music 🎵 which juxtaposes extremes with Zimbabweans singing ‘Tesco’s our dear friend’ 🎤(Holt in Cook et al., np; Friedberg, 2004). Juxtaposition is useful to filmmakers cos it helps highlight stark inequalities (Wenzel, 2011)!

A juxtaposition 👨🏫 masterclass………

Mark ⬆️ demands farmworkers trim the 🫛 leaves for the consumer’s benefit …! Grannie ⬇️ explains her past traumas while a British consumer at a dinner party ⬇️ says workers – like Grannie – ‘are probably happy in their mud hut’ (O’Malley in Cook et al., 2025, np).

These tactics juxtaposes British consumers 🤵♂️ with Zimbabwean farmworkers 👩🏾🌾 leading to a response of these consumers are insane – they’re called arrogant, bstards, and c&*ts (in Cook et al., 2025). Contrasting consumers with producers provokes viewers to rally 🪧 against the dinner party guests (Wenzel, 2011). Viewers were so angry 😡 at Tesco 👿 that they wanted to ‘kick in the TV’ 📺 (Jema in Cook et al., 2025, np). Anger helps prompt action by breaking viewer passivity (Chouliaraki, 2010). In response to Mangetout, Tesco joined the Ethical Trade Initiative showing ‘the ability of film to intervene in the foodscape’ (Richardson-Ngwenya & Richardson in Cook et al., 2025, np). Corporations changed 💥💥💥 because of political consumerism (Stolle & Micheletti 2013).

Effective. Intentions → Impacts. But just a word of warning, triggering tooooo strong emotions can backfire. Chouliaraki (2010) – worth a read 📚 btw warns of the boomerang (viewers resent blame, shame & guilt tactics ) and bystander effects (viewers feels powerless 😬). The trick is to deliver enough emotion to spark action 🧨 without triggering paralysis or resentment .

But The ginger 🫚 trail doesn’t trigger strong emotions at all. 👎 A major flaw?

It’s an I-Doc 🎦. Viewers choose clips 📽 and in what order they’re watched. Interactivity facilitates participation in making a film rather than simply consuming it → this immerses viewers (Aston, 2022). This film teaches economic geographies (Ananthanarayana, 2025). It shows slow violence caused by ginger cultivation but it’s hard to show violence that takes place over many years ⏳ (ibid; Davies, 2022). It overcomes this by showing communities suffering consequences of slow violence which impacts viewers emotionally 💓 which is what Davies (2022) recommends!

Viewers wanted to find out more. To ‘work out the puzzle 🧩 of seemingly disconnected clips’ (Anon in Ananthanarayana, 2025, np). But responses were ‘not emotionally charged’ 🤦♂️ (ibid). Still, now we’re talking; viewers ‘told their house about the film’ (ibid). 🆒 Knowledge is dispersed. But was this an effective film?

IMO…No. It nailed interactivity. But the lack of emotional response means the film risks creating passive awareness 🤷♀️ rather than action (Nash and Corner, 2016). Films have to get the viewer emotionally.

That’s where Ghosts 👻 comes in. A fictional film. Based on the ‘true story’ (Broomfield in Allen et al., 2025, np) of 23 Chinese migrant workers who died 💀 at Morecambe Bay in 2004. It tells the truth 💯 and shows capitalist evils by telling the story of Ai Qin and ‘the chain of labour that exploits illegal immigrants’ (Romney in ibid). Telling stories are effective as they help viewers connect to characters which moves them emotionally 💓 (Nash and Corner, 2016). The film created characters AND found characters! Lead actors were Chinese migrants → ‘neither actors nor themselves’ (Martin in Allen et al., 2025, np).

Oh and also, Ghosts showed the violence 😡→🤕 workers endured in Morecambe bay forcing the viewer to imagine themselves there (Wenzel, 2011). These tactics combine to include (so much raw) emotion in Ghosts meaning viewers know ‘this is the real thing’ (Anon in Allen et al., 2025, np).

workers’ (Martin in ibid).

Then I cried 😭. Having built an attachment to the workers, having seen the violence they were victims of, the scene where they drown 🏊♀️ was TOO MUCH! It’s difficult ‘ NOT to cry’ (Johnjoe66 in ibid). Viewers feel helpless which combined with feeling so sad 😞 they just cry 😭 (Frome, 2014). Ghosts shows how ‘unchecked capitalism haunt[s] this deeply felt film’ (Geall in Allen et al. 2025, np). Ugggh, capitalism is sh*t! ← 😢 😡 😩 🤮.

But … something positive … debts were paid off ← ‘the crippling debts inherited by the families of the victims of the Morecambe Bay Tragedy have been paid off’ (Anon in ibid).

Emotion + Knowledge = Action❗️2008 → 2025 and a film still makes me 😭. Ghosts 👻 worked.

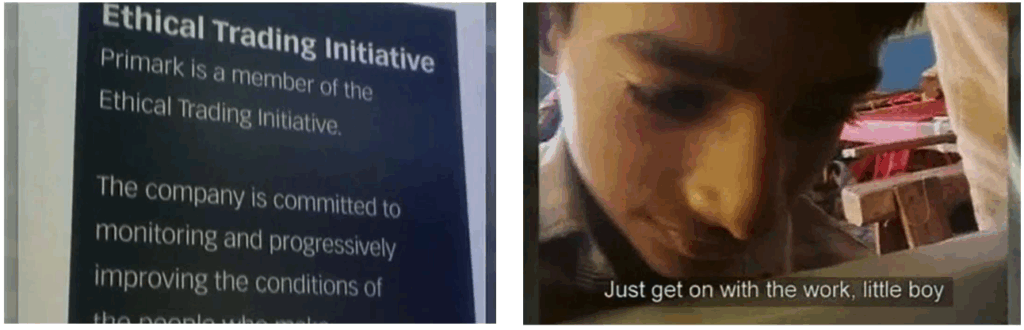

Now, Primark on the rack 👕👗 worked but wait for the 👀 twist. It showed capitalist evils by exposing Primark’s suppliers using child refugees from Sri Lanka as wage labourers in India, earning just ’19p a day’ 😞 (Williams in Adley et al., 2025, np). Capitalism f*cking failed these people (Chellan, 2023). By targeting the right brand – one with ‘170 stores nationwide’ (Williams in Adley et a., 2025, np), filmmakers tried to change corporate behaviour by ‘set[ting] up [their] target’ 🎯 (Maroney in ibid). Exposing the discrepancies between Primark’s brand image and reality hit 👊 them hard ← exploiting their corporate vulnerabilities ❌ ruining reputations, provoking them to change (Micheletti & Stolle, 2008; Cook et al., 2019).

Want a strong reaction? Like Girl Model, include suffering kids 🔀 Capitalism is sh*t ← ‘An inequality-enhancing machine’ 🏭 (Wright, 2015, np).

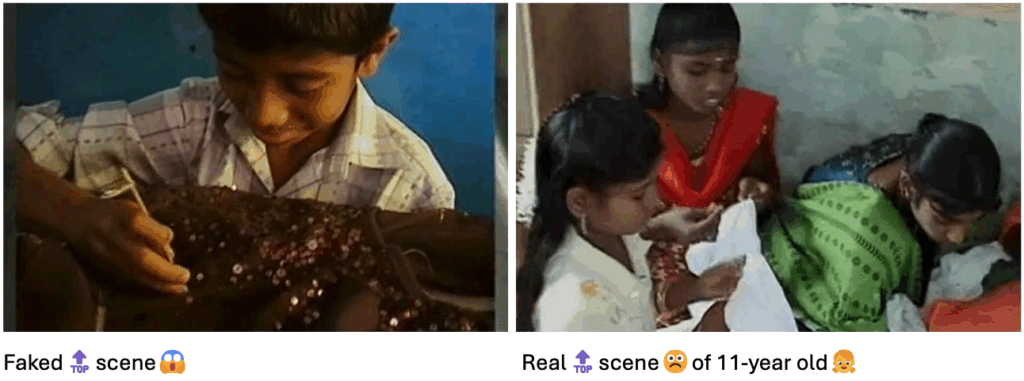

BUT THERE’S A PROBLEM!!! The filmmakers [allegedly] ⚠️ fabricated ⚠️ a scene of children working in Bangalore – the ‘footage was not authentic’ (Greenslade in Adley et al., 2025, np). Child exploitation is socially unacceptable, and I think the filmmakers 🎥 took advantage of this to incite 😡 😢 😩 🤮 (Aguigar et al., 2008). Primark tried to silence 🤐 their critics by challenging the filmmakers but this backfired because of the Streisand Effect → activism was publicised 🤯 (Cook et al., 2018). Prioritising PR 🧯drew more attention 👀 to their exploitation… ‘what about the other children that featured in THE REST OF THE ONE HOUR FILM’ (emilynew in Adley et al, 2025, np).

With public outcry magnified 🔎, corporations changed. In 2013, the Rana Plaza clothes factory collapsed killing over 1,100 people in Dhaka, Bangladesh (Cook et al., 2018). Primark’s response was to spend £9 million 💰to support local communities – or to (try) cover their arses (ibid).

An EFFECTIVE film. But the filmmaker who exposed Primark also found out (ibid). The film would have triggered the desired anti-capitalist reaction without the fake footage ← something to avoid 🚫 when making your film!

Uh-oh, back to Rana Plaza. I’m welling up. But I’m crying 😭 because UDITA is inspiring.

Over 5 years, UDITA follows female garment factory workers in their mission for justice before and after Rana Plaza. Ending violence and exploitation was the goal – ‘Udita shows the agency of these women’ (Minney in Barker et al., 2025, np) to overcome injustice. It encourages feminist 🤜🏻🤛🏽 solidarities giving women greater confidence and knowledge to DEMAND their rights (Hale & Willis, 2007). Its ‘just the workers voices’🗣 (Rainbow Collective in Barker et al., 2025, np).

In UDITA – workers take the mic 🎙! Collective action is key to taking down capitalism (McLaren, 2019). By finding and giving 🌞 inspiration – ‘like the inspirational Ratna Miah’ (Hoskins in Barker et al., 2025, np), there is one overriding response: these people are ‘inspiring on a global level’ (ibid) 🌍. Inspiration is powerful ✊🏽 cos it encourages the viewer to emulate the inspiring women in UDITA (Thrash and Elliot, 2003). And the best bit? It worked alongside other emotions. This is so sad. I’m so angry. This gives me hope (Season Bangla Drama in Barker et al., 2025, np).

This hope encourages other people to continue with their own activism (Brown & Pickerell, 2009). UDITA inspired activism as people globally challenge injustice through their own community campaigns 🤗 -‘I am filming everything to collect evidence for our own community campaign’ (Salmon in Barker et al., 2025, np). And there’s more! Governments intervened. In France, legislation changed because ‘Rana Plaza was covered by newspapers, petition of NGOs, film, documentary’ (Evans in ibid) like UDITA. 🤩 WHOA! That’s real change ✊🏽.

RIGHT, so what’s my answer???

Effective films use emotions 😡 😢 😭 😩 🤮 🤗 🤯 🤩 to provoke responses that galvanise action. So think carefully before locking in your theory of change. Choose the emotion that won’t let go – then hit 🔘 ‘record.’ By shaking viewers emotionally and making them feel injustice, you’re not just making a documentary – you’re starting a movement ✊🏽.

Think of Nadya 😭, Grannie 😡, Ai Qin 🏊♀️, the children 👧 of Primark, and the women 🧕🏽🧕🏽🧕🏽 of Dhaka.

Effective films ignite emotion. Now you know. Get out there and inspire change! ✨

SOURCES

Adley, K., Keeble, R., Russell, P., Stenholm, N., Strang, W. and Valo, T. (2025) Primark – On The Rack. followthethings.com (https://followthethings.com/?p=2655 last accessed 27 April 2025)

Aguigar, P., Vala, J., Correia, I. & Pereira, C. (2008) Justice in Our World and in that of Others: Belief in a Just World and Reactions to Victims. Social Justice Research 21(1), p. 50-68.

Allen, H., Heaume, E., Heeley, L., Hedger, R., Johnson, S., McGregor, O. and Webber, L. (2025). Ghosts. followthethings.com (https://followthethings.com/?p=10357 last accessed 27 April 2025)

Ananthanarayana, B. (2025) Untitled [Q&A video & transcript], GEO3123: Geographies of material culture. University of Exeter.

+28 sources

Aston, J. (2022) Interactive Documentary: Re-setting the Field. Interactive Film and Media Journal 2(4), p.7-18

Bannister, L. & Bergan, R. (2023) A timeline of UK trade and trade justice. London: Trade Justice Movement

Barker, T., Collier, J., Baker, A., Coppen, L. and Eve, H. (2025) UDITA (ARISE). followthethings.com (https://followthethings.com/?p=1593 last accessed 27 April 2025)

Brown, G. & Pickerell, J. (2009) Space for emotion in the spcaes of activism. Emotion, space, & society 2, p.24-35

Callon, M. (1998) An essay on framing & overflowing: economic externalities revisited by sociology. The sociological review 46(1), p.244–269

Chellan, N. (2023) The life of capitalism. in his F/Ailing capitalism and the challenge of COVID-19. Leiden: Brill, p.180-216

Chouliaraki, L. (2010) Post-humanitarianism Huamitarian communication beyond a politics of pity. International journal of cultural studies 13(2), p.107-126

Cook et al, I. (2018) Inviting construction: Primark, Rana Plaza and Political LEGO. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 43(3), p.477-495

Cook et al, I. (2019) A new vocabulary for cultural–economic geography? Dialogues in Human Geography 9(1), p.83-87

Cook et al, I. (2025) Mangetout. followthethings.com (https://followthethings.com/mange-tout.shtml last accessed 27 April 2025)

Cook et al, I. (2002) Commodities: the DNA of capitalism. (https://followtheblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/commodities_dna.pdf last accessed 27 April 2025)

Dant, T. (2012) Mediating morality. in his Television and the moral imaginary. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 147-178

Davies, T.,(2022) Slow violence and toxic geographies: ‘Out of sight’ to whom? Politics and Space 40(2), p.409-427

Duncombe, S. (2023) A Theory of Change for Artistic Activism. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 81, p.260-268

Friedberg, S. (2004) The ethical complex of corporate food power. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 22, p.513-531

Frome, J. (2014) Melodrama and the psychology of tears. Projections 8(1), p.23–40

Hale, A. & Willis, J. (2007) Women Working Worldwide: transnational networks, corporate social responsibility and action research. Global Networks 7(4), p.453-476

Hambley, A., King, E., Keogh, A., Renny-Smith, C., Callow, E., Thorogood, J. & Alloy, V. (2025) Girl Model: The Truth Behind The Glamour. followthethings.com (https://followthethings.com/girl-model.shtml last accessed 27 April 2025)

Kemp, D. (2025) Comparing disgust and sadness: examining the interaction of emotion and information in charity appeals. Journal of Social Marketing [online early], pp. 42-58.

McLaren, M. (2019) Global Gender Justice: Human Rights and Political Responsibility. Critical Horizons 20(2), p.127-144.

Micheletti, M. & Stolle, D. (2008) Fashioning social justice through political consumerism, capitalism and the internet. Cultural Studies 22(5), p.749-769

Nash, K. & Corner, J. (2016) Strategic impact documentary: contexts of production & social intervention. European journal of communication 31(3), p.227–242

Natter, W. & Jones III. J.P. (1993) Pets or meat: class, ideology & space in Roger & Me. Antipode 25(2), p.140-158

Ryynänen, M., Kosonen, H. & Ylönen, S. (2023) From visceral to the aesthetic: tracing disgust in contemporary culture. in their (eds.) Cultural Approaches to Disgust and the Visceral. London: Routledge, p.3-16

Stolle, D. & Micheletti, M. (2013) Does political consumerism matter? Effectiveness and limits of political consumer activism repertoires. in their Political consumerism: global responsibility in action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p.204-243

Thrash, T. & Elliot, A. (2003) Inspiration as a Psychological Construct. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 84(4), p.871-889

Wenzel, J. (2011) Consumption for the common good? Commodity biography film in an age of postconsumerism. Public culture 23(3), p.573-602

Eric Olin Wright (2015) How to be an anti-capitalist today. Jacobin 12 February (https://jacobin.com/2015/12/erik-olin-wright-real-utopias-anticapitalism-democracy/ last accessed 27 April 2025)

Image credits

Icon: conversation (https://thenounproject.com/icon/conversation-6769395/) by kliwir art from Noun Project (CC BY 3.0)

Girl model screenshots: credit Carnivalesque Films

Mangetout: credit BBC

The ginger trail: credit Bharath Ananthanarayana

Ghosts: credit Beyond Films

Primark on the rack: credit BBC.

Handbook screengrabs: credit followthethings.com

SECTION: advice

Written by Luke Elkington, edited by Ian Cook (first published July 2025)

![]()