followthethings.com

Follow it yourself (page) | Follow it yourself (examples) | Health & Beauty (⏵ example)

“Who made my stuff?” | example ⏵ Gillete Razor Blades

A ‘follow it yourself’ detective work task suitable for activists, journalists, filmmakers, artists, researchers, teachers and students

CEO Ian’s ‘Traces of labour’ YouTube playlist embedded above. Can be used as a task / lesson taster. The jeans paper mentioned is Hauser (2004)

Behind the followthethings.com website lies a university undergraduate module called ‘Geographies of material culture’ taught be CEO Ian from 2000 to 2025. The first version of the module (2000-2008) encouraged students to do some online detective work to see if they could find out who had made a commodity that mattered to them. He wanted his students to appreciate if and how their everyday lives were made possible – in part – by the work done by supply chain workers elsewhere in the world. He wanted to them to find out, and think, about the responsibilities that they and others had for any trade injustices they found in the process. The results were always surprising, and Ian started to share some of their writing (with permission) with geography school teachers which led Ian and his students being invited to publish some in teacher-facing journals (see Angus et al 2001, Cook et al 2006, 2007a&b). Because this detective work always began in their personal worlds of consumption, Ian was invited to bring this ‘follow it yourself’ approach into a Geographical Association and Royal Geographical Society project called the ‘Action Plan for Geography’ (see Martin 2008, Griffiths 2009). This, in turn, helped the ‘follow the thing’ approach to gain a wider audience after it the GA and RGS wanted it to be included in the 2013 UK National Curriculum for Geography as a means to teach students about trade (see Parkinson & Cook 2013, University of Exeter 2014). Ian taught this approach to trainee geography teachers at the University of Nottingham who tried this out on their placements and wrote #followtheteachers posts for the followthethings.com blog (see Whipp 2013). It was also fleshed out in the ‘Who made my clothes?” online course that Ian co-authored and presented for the Fashion Revolution movement (Cook et al 2017-2018: see here). There’s one main principle in this ‘follow it yourself’ work: if you know how and where to look, you can find a connection between your life and the lives of others who have made anything that matters to you, anything that’s part of your life. There’s been an explosion of journalism, NGO activism, academic research and corporate social responsibility initiatives relating to trade justice since the 1990s that means that there are secondary data sources that you can find, sift and create a story about anything that comes from anywhere – or so it seems. Doing this detective work in groups can encourage diverse learners to share their expertise (e.g. by drawing on their experiences of living in different parts of the world, and being able to research in different languages: see Bowstead 2014). Doing it for younger learners can motivate them to write (e.g. by asking them what they would say to the person who picked the cocoa in their Milky Bar buttons, for example – see Lambert 2015). And doing his kind of thing as an academic researcher can help you to produce ‘follow the thing’ publications (see Taffell 2022). We have updated the advice we gave in the 2000s and set it out below as a three stage process: A – reading the results of other ‘follow it yourself’ research; B – choosing the thing you want to follow; and C – doing the ‘follow it yourself’ detective work to find out who made it for you and the trade justice issues that come with this. To illustrate what this research is like to do, what sources you can find where, and how to find and follow a productive trail, we have researched a new example from start to finish: who made Ian’s pack of Gillette razor blades? Just click ⏵ example to find out.

Page reference: Ian Cook et al (2025) Who made my stuff? followthethings.com/who-made-my-stuff.shtml (last accessed <add date here>)

Estimated reading time (including example detective work): 80 minutes

Stage A: read what you will write

You may be a teacher who has asked their students to suggest commodities that they’ll research and report back on, or you make like to do this yourself. You may be a journalist or a researcher scoping testing out a hunch you have for some new ‘follow the thing’ trade justice research. Regardless of your starting point, it’s good to begin by looking at the kind of detective work you’re going to do and the writing that might create from this.

We suggest you read at least two of the ‘follow it yourself’ examples published on followthethings.com on a door key, a pair of socks, a stick of chewing gum, a banknote, an iPod, a contraceptive pill, a thyroxine tablet, toothpaste, a pair of ballet shoes, a rifle sight and a mirror?

As you do this, you could consider the following questions and write some brief answer to discuss later.

- What kinds of commodities do the authors choose to study? How are they important to their lives?

- How do the authors try to make personal connections with the people who make these commodities for them?

- How do they try to grab you as a reader to understand – and feel – these connections too?

- What kinds of sources do they use for this detective work? How reliable do they seem to be?

- What emotions are churned up, both for them as authors and for you as a reader?

- What difference do you think this research and writing can make?

Stage B: choose the thing to follow

To make your connection to supply chain workers both personal and surprising, it’s important to choose a commodity that matters to you but which you know little or nothing about. Think about something that you use every day (like the socks you put on every morning, the mirror you check yourself in, the meds you take); something that you always carry with you (like money, something to listen to music on, your keys); something that’s essential for your favourite pastime, sport or hobby (like ballet shoes, a rifle sight), something that’s jumped into your world and said ‘research me!’ (like the chewing gum you trod in 😵), but always something whose origins you know little or nothing about. The task is not to illustrate what you suspect or already know about! Give yourself a chance to be surprised.

example

Gillete Razor Blades (pack of 8)

We will illustrate this ‘follow it yourself’ approach through a simple example: a pack of Gilette Fusion 8 razor blades that CEO Ian bought from his local supermarket for £20 while he was writing this page. It may not be an example that you might choose but follow us down this rabbit hole to get a sense of how you could follow your own thing through some simple internet searching.

DON’T PLAY SAFE! Have confidence that whatever you choose will be a productive choice. And have confidence that you will be able to find something about somebody who may have helped to make it for you, and that there will be some resistance and activism to any trade injustice that they experience (usually a form of exploitation – there’s more on this on our 🧐 About page). What you’re looking for is circumstantial evidence that this relationship existed in the supply chain that created that commodity for you to use.

Circumstantial evidence is indirect evidence that does not, on its face, prove a fact in issue but gives rise to a logical inference that the fact exists. Circumstantial evidence requires drawing additional reasonable inferences in order to support the claim (Cornell Law School 2022, np).

We’ll show you what we mean in the ⏵ example sections below as we try to answer the seven detective work questions for the commodity we chose to follow. Good luck 😉.

Stage C: do your detective work

Take the commodity / thing that you have chosen. Carefully inspect its packaging, and the thing itself. Then try to answer the 7 questions below through by doing some online research.

Think about Segei Tret’iakov’s (2006) inspiration for studying the ‘biography of the object’. The compositional structure is a conveyor belt. Every segment introduces new people. Each one comes into contact with that object because of their social status and their skills. Creating a biography of your object will cut across classes. It could help you to see how society works in an interdependent and progressive way because new politics can emerge from understanding economic activity in this way (there’s more on this on our 🧐 About page). At this stage you should have no idea where you’re about to go, and who you will meet along the way…

1. what is your chosen commodity for?

QUESTIONS: Why would you have such a thing in your life? What does it do for you? How does it leave its mark?

This detective work starts close to home. ‘Follow it yourself’ detective work hopes to bring worlds of consumption and production closer together. So we start with questions about your chosen commodity’s ‘use value’. However obvious your answers may be, write them down!

example

For Ian’s packet of razor blades these notes could start with the fact that hair grows on the human body, and that some of it needs to be removed now and again. A razor blade, especially when it’s new, can cut that hair off close to the skin leaving a smooth surface. People shave this hair off for comfort, for looks, for cultural, religious or other reasons. Sometimes, if you’re not careful, shaving with a razor blade can nick your skin and cause bleeding, or it can leave a rash. The blades get blunt after repeated use, are uncomfortable to use, get thrown in the trash, and need replacing. That’s why Ian bought that pack of 8.

2. how does it come into and out of your life?

QUESTIONS: Where did you get it from? Where do you keep it? What else need to be there for it to work? What waste does it help to create? Where does that go?

This is where you begin to ask questions about your chosen commodity’s supply chain, and the role that you play in its life story.

example

For Ian’s notes here, he could write how he bought this from his local supermarket. Put it in a cupboard in the bathroom. Popped the blunt blade cartridge in the bathroom bin, opened the new packet of blades, and clicked a new blade cartridge into the handle. He had to buy the Gillette cartridges because they’re the only ones that fit the Gillette handle he bought years ago. He had also bought some shaving gel (for sensitive skin) and needed some water to create a foam to softens his facial hair before shaving. Sometimes you may need to do some internet searching to explain some details:

Search ‘what does shaving foam do?’ ➡️ “Think of shaving cream, gel, and foam as a lubricant for your razor to help it glide over the surface of your face to prevent nicks and cuts. Without shaving cream, there will be a lot of (uncomfortable) friction between your skin and your razor, which is going to cause irritation, ingrown hairs, and stop you from getting a close shave” (Pearl Chemist Group Limited 2022, np).

This is where you may start to wonder if you should follow shaving gel and water as well. As well as taps, sinks, mirrors, towels, aftershave, everything else that feeds into the act of shaving. No commodity works alone. There are so many threads that you could potentially follow. Including the packaging for those blades, the receipt from the supermarket, the contactless payment, the bag you brought them home in, it’s endless. But we have to keep focused, try to follow one of these threads as far as you can. Back to the task…

3. what does it tell you about itself and its life?

QUESTIONS: What information is available on the packaging, on its labels, on its surfaces? Does it say where it’s made? Is there a postal address or website? Is there a list of ingredients?

These are the first clues that you can use in the internet searches that will help answer the next set of questions.

example

Here are some photos of Ian’s razor blade package, the surfaces that contain information. Take a close look. What can his packaging tell us about the origins of this thing? What details could become search terms for your detective work?

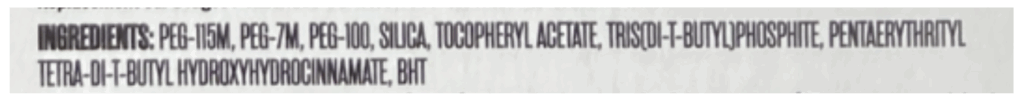

There’s a barcode (you can type the numbers into a barcode lookup (which won’t tell you much more than you already know) and if you scan the QR code it takes you to the Gillette website (it’s always interesting to see what a corporation says about itself, but we can’t rely only on this information!). There’s more helpful information on the bottom of the packet. Here, we can see that they are ‘Made in Germany’ and that, if we want to call the company from the UK, Ireland, Sweden, Denmark, Finland or Norway, telephone numbers are provided if you want to call them. The postal addresses of Proctor & Gamble (which owns the Gillette brand) in Germany and the UK are listed if you want to write to the company, visit it, or at least look it up on Google streetview. That’s worth doing anywhere along your commodity’s supply chain, as we will see later. Gillette and its tagline ‘THE BEST A MAN CAN GET’ could be fun to play with in your writing. We can also zoom in on the ingredients list on the back of the packaging. We’ve copied it below and added links to information we’ve found online about what each is and does: PEG-115M, PEG-7M, PEG-100, Silica, Tocopheryl Acetate, Tris(di-t-butyl)phosphate, Pentaerythrityl Tetra-Di-T-Butyl Hydroxyhydrocinnamate & BHT. You could follow any and all of these ingredients – they all come from somewhere, from workers in many other supply chains. But we’re going to concentrate on the razor blades (whose ingredients are not listed on the packaging!). We have to look elsewhere for those.

What we’re taking forward from this stage of the research is one simple point: these razor blades were ‘Made in Germany’ and they’re supposed to be ‘The Best A Man Can Get’. Let’s see.

4. what is it made from, where in the world?

QUESTIONS: What is your chosen commodity made from? How, and by which companies, are its materials sourced and processed? How are they made into this this thing? How do they give this commodity the properties it needs to do its job? Where is all of this taking place?

This is where you start to trace the commodity’s supply chain back from the place where you first acquired it.

🕵 Suggested online searches: ‘[your chosen thing]’ + ‘wikipedia’; ‘[an ingredient in your thing]’ + ‘wikipedia’; then follow-up searches using keywords you find in the results.

example

Here, we’re using basic keyword searches on an internet browser to find some answers in YouTube videos, Wikipedia entries, company reports, online newspapers, and specialist industry websites. We’re using this research to piece together the journey of this commodity from raw materials to finished product. All we know so far is that these blades were ‘Made in Germany’. But let’s start by finding out what razor blades are made from.

Search ‘razor blades’ + ‘wikipedia’ ➡️ “Razor blade steel, also known as razor steel, is a special type of stainless steel designed specifically to be used as a razor blade. Its defining characteristics are its chemical composition and shape. Jindal Stainless is the world’s largest producer of razor blade stainless steel. Razor blade steel is a martensitic stainless steel with a composition of chromium between 12 and 14.5%, a carbon content of approximately 0.6%, and the remainder iron and trace elements” (Wikipedia nda, np).

OK, so let’s find more detail about this ‘martensitic steel’:

Search ‘martensitic steel’ + ‘wikipedia‘ ➡️ “Martensite is a very hard form of steel crystalline structure. It is named after German metallurgist Adolf Martens. … Martensite is formed in carbon steels by the rapid cooling (quenching) of the austenite form of iron at such a high rate that carbon atoms do not have time to diffuse out of the crystal structure in large enough quantities to form cementite (Fe3C)” (Wikipedia ndc, np).

And lets’ find out more about this Jindal company that is the world’s largest producer of this steel:

Search ‘martensitic steel’ + ‘Jindal‘ ➡️ “The speciality Product Complex [at Jindal’s Hisar factory] has a capacity of 25,000 tons per annum of precision cold rolled strips. This complex processes mainly Martensitic Stainless Steel for razor blade manufacturing” (Di Napoli & Naidu 2024, np).

Follow-up search ‘where is Hisar?’ ➡️ “Hisar … is the administrative headquarters of Hisar district in the state of Haryana in northwestern India” (Wikipedia ndd, np).

So let’s investigate Jindal’s supply chain. The main ingredient of martensitic stainless steel is iron:

Follow-up search ‘iron ore’ + ‘supply’ + ‘Jindal’ + ‘India‘ ➡️ “Jindal Steel and Power, has formalised a 50-year mining lease for the Roida-I Iron Ore and Manganese Block located in the Keonjhar district of Odisha through a Letter of Intent (LOI) from the Government of Odisha” (Anon 2025, np).

Follow-up search ‘where is Odisha?’ ➡️ “Odisha … is a state located in Eastern India” (Wikipedia ndb, np).

So Jindal has a martensitic stainless steel plant in Hisar state, and a new iron ore mine in Odisha state, in India. OK. Next, if Jindal is the world’s largest producer of this type of stainless steel, do they supply it to Gillette?

Search ‘Jindal’ + ‘Gillette‘ ➡️ “A Reuters analysis of import records over the past four years shows that [Gillette parent company Proctor & Gamble] has shifted where it buys the stainless steel for its top grooming brands in the United States, its biggest market, to a cheaper Indian manufacturer, a move that may help it offset higher costs in Trump’s second term. The Cincinnati-based company now primarily obtains the steel for Gillette from New Delhi-based Jindal Stainless … according to the U.S. import records for P&G subsidiaries, including Gillette” (Di Napoli & Naidu 2024, np).

Follow-up search ‘Does Gillette’s German factory source from Jindal Steel?‘ ➡️ “Recognizing Jindal Stainless as one of its prestigious partners, the P&G [Proctor & Gamble] conglomerate has felicitated the Company with its Grooming Excellence Award 2022. The award recognizes P&G’s top-performing external business partners annually in the operational, innovations, and relationship performance categories. Jindal Stainless has been selected from the ranks of more than 50,000 external business partners. The Company has been awarded for being a consistently reliable partner to P&G’s Gillette brand through its innovative solutions and supply of high-quality stainless steel. It is noteworthy that Jindal Stainless is the approved global supplier across all the units of Gillette” (Jindal Stainless 2022, np: emphasis added).

Follow-up search ‘Where in Germany does Gillette manufacture razor blades?‘ ➡️ “At our Berlin factory, the best, sharpest and most innovative razor blades are produced, including PRO, Fusion5, Mach3 and SkinGuard Sensitive blades, encompassing different kinds of razor blade technology” (Gillette nda, np).

Through these online searches, we have found that the razor blades we are following are made from ‘martensitic stainless steel’ whose main ingredient is iron ore. We have found that the Gillette razor blade factory in Germany where our blades were made uses martensitic steel bought from an Indian company called Jindal which makes that steel in the state or Hisar, and mines its ore in the state of Odisha. We know that this iron ore and stainless steel goes through a series of processes to give it the qualities that razor blade steel needs. We have the circumstantial evidence to make a convincing case that this is an important supply chain for the razor blades that we’re following.

5. what trade justice issues can you find there?

QUESTIONS: What is like to work, and live near, the places where this commodity is made? And where its raw materials are sourced? Is there evidence of exploitation of people and the environment?

This is where you start to look for concerns about trade injustice in the supply chain of your chosen thing.

🕵 Suggested online searches: ‘[ingredient found before]’ +/or ‘[site of production found before]’ +/or ‘[company found before]’ + ‘occupational health’ or ‘industrial toxicology’; then follow-up searches using keywords you find in the results.

example

In the previous stage of this research, we found three sites of production: an iron ore mine in Odisha, a steel mill in Hisar, and a razor blade factory in Berlin. So how do we find out if there are trade injustices in these places?

Two of our first search hits were videos posted on YouTube by Gillette Germany to explain what it’s like to work in their razor blade factory in Berlin and by Jindal Steel & Power (JSP) about their history and operations in India and around the world. Corporate videos can contain useful information to include in later searches, and can be valuable to see what corporations claim about their commitments to workers, communities and the environment. They also allow us to look around, get a sense of the workplaces we’ve so far only read about.

Every YouTube video has a transcript, and you can copy parts that you find interesting into your notes. The claims that companies make about their commitments to workers and the communities where they live are important to note when you’re investigating trade justice in their supply chains. Here’s what we picked up from the Jindal Steel & Power (JSP) transcript:

“JSP’s tradition has been to put people first, be it its’ employees, communities and investors. Amongst its various activities, JSP Foundation also runs a unique initiative … to promote, preserve and propagate tribal arts and crafts of India through its key initiatives … The foundation has brought a positive change in the lives of communities around its plants in its endeavour to provide quality and affordable healthcare to the local communities and societies at large” (Jindal Steel 2023, np).

But we can’t rely only on what corporations say about themselves. Perhaps the most independent sources for trade justice research are two fields of public medicine called ‘occupational health’ and ‘occupational toxicology’. Let’s see if we can find any studies along our razor blades’ supply chain:

Search ‘iron ore mining Odisha occupational health jindal’ ➡️ “mine workers are regularly exposed to dust of various potential pollutants and toxicants present in the mining environment such as chromium, lead, mercury, cadmium, manganese, aluminium, fluoride, arsenic, etc. Inhalation and absorption through the skin are common routes of exposure. … Chromium (Cr) is considered an essential nutrient and a health hazard. Specifically, Cr in oxidation state +6, is considered harmful even in small intake quantity whereas Cr in oxidation state +3, is considered essential for good health in moderate intake” (Das & Singh 2023, p.6).

Even though we searched for iron ore mining, the article we found is about chromite mining in the state of Odisha in India. Chromite is the ore from which chromium is extracted. And, as we found earlier, chromium is an ingredient in the martensitic stainless steel that razor blades are made from. And Jindal opened an opencast chromite mine in Odisha’s Sukinda Valley in 2002, Das & Singh (2023) note. So let’s stick with chromite and chromium for a while. What does chromium add to martensitic stainless steel, and what properties would this give to these razor blades?

Search ‘chromium properties martensitic stainless steel’ ➡️ “The properties of chromium that makes it most versatile and important are its resistance to corrosion, oxidation and hardenability” (Mishra & Sahu 2013, p287-8).

And what properties does Chromite and Chromium mining give to the places where they are mined?

Search ‘iron ore mining Odisha occupational health jindal’ ➡️ “Chromium (Cr) is considered an essential nutrient and a health hazard. Specifically, Cr in oxidation state +6, is considered harmful even in small intake quantity whereas Cr in oxidation state +3, is considered essential for good health in moderate intake” (Das & Singh 2023, p.6).

Search ‘chromium properties martensitic stainless steel’ ➡️ “… hexavalent chromium (Cr+6 [CR(VI]) … is considered by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) to be a human carcinogen” (Mishra & Sahu 2013, p288 & 290).

So, chromium helps Gillette’s razor blades to give a close shave but chromite mining is extremely hazardous to human health. So what’s it like to work in (and live nearby) Jindal’s chromite mine in Odisha’s Sukinda Valley? Back to what we found in an earlier search:

Search ‘iron ore mining Odisha occupational health jindal’ ➡️ “In India, the Sukinda valley of Odisha contains 98% of the countries chromite ore deposits …and is considered as one of the prime open cast chromite ore mines … of the world over an area covering approximately 200 sq. km., in the Jaipur district” (Das & Singh 2023, p.6).

Search ‘iron ore mining Odisha occupational health jindal’ ➡️ “Currently, 20 opencast and two underground mines are operational in the valley generating about 160 million tons (MT) of overburden [the surface layers of soil and rock that have to be dug through to get to the ore]. It also releases 11.73 tons of Cr(VI) to the environment every year, making it the fourth-worst polluted places in the world. Chromium mining in Sukinda Valley had, therefore, resulted in major biodiversity loss and severe health impact for locals human population” (Nayak et al 2020, p.2).

So what does opencast chromite mining involve, and how does this pollute the environment?

Search ‘how does open cast chromate mining take place?’ ➡️ “Chrome mining is the process of extracting chromite ore (FeCr₂O₄), the primary source of chromium, from the earth. The steps involved in chrome mining typically follow this general sequence. … Open-pit mining (for shallow deposits): Remove overburden (surface material covering ore). Drill, blast, and excavate chromite ore. … Reduce ore size for processing. … Crush ore into smaller pieces using crushers. Further grind crushed ore into fine particles using grinding mills. … Separate chromite from waste material (gangue). … Techniques: Gravity separation: Use water and gravity to separate chromite, which has a higher density than gangue. Magnetic separation: Remove magnetically susceptible materials from the ore. Flotation: A chemical process that separates chromite from other minerals based on surface properties. Manage waste materials. Process: Tailings (leftover material after processing) are stored in tailings dams or repurposed for land reclamation. Efforts are made to minimize environmental impact” (Sheena 2025, np).

We found a video about another company’s – Tata’s – chromium mine in the Sukinda Valley. It was made in 2017, but it gives a vivid sense of the scale, processes and hazards of chromite mining.

Back to our search for the occupational health risks that this video hints at:

Search ‘iron ore mining Odisha occupational health jindal’ ➡️ “The environmental impacts of chromite mining in Sukinda valley are: … Presence of hexavalent chromium in mine drainage water – Open cast mining in the Sukinda valley is carried out at a depth below ground water table resulting seepage of ground water into the mine pit. Large volumes of seepage water are the source of a serious hazard … Dust generation – Large amount of dust is generated during the chromite mining activity, particularly from drilling, blasting and transportation. Stacking and loading of both ores and chromite overburdens [the rock and soil that has to be removed to access the chromite below] also generate some amount of particulate matter. … Overburden generation – Open cast chromite mining generates large quantity of over burden. … If it is not protected / treated properly then runoff from these over burden can pollute the nearby surface as well as ground water bodies due to leaching of hexavalent chromium. … Loss of biodiversity and forest – Most of the chromite deposits are located in forest areas. Chromite mining therefore causes loss of forest cover and decrease the plant as well as animal diversity” (Mishra & Sahu 2013, p289-90).

Search ‘iron ore mining Odisha occupational health jindal’ ➡️ “Almost all of the chromite mines in Sukinda directly or indirectly release water containing Cr (VI) [aka +6 or hexavalent] concentrations into the Damsala river which deteriorates the water quality at worst level. The crucial fact is that most of such rivers and streams empty themselves into the Brahmani river, which is the lifeline of several districts. … 70 million tonnes of overburden have been stockpiled in the valley over the last six decades which contributes to the heavy concentration of Cr (VI) to the surface and groundwater of the area. Slowly but surely, the carcinogen has entered into the food chain and affected the lives of the people of the region. [One] … report indicated that most wells and water courses in Sukinda valley were contaminated by Cr (VI) up to a value of 3.4 mg/L in surface water and 0.6 mg/L in groundwater, against a permissible limit of 0.050 mg/L” (Das & Singh 2023, p.11).

So how does the hexavalent chromium that’s polluting this part of India affect the people who work and live there?

Search ‘iron ore mining Odisha occupational health jindal’ ➡️ “About 7000 people are directly employed by chromite mines while that depends on Brahmani river for water and sustenance is around 2.6 million. Seventy percent of surface water sample and 60% discharge water sample contained hexavalent chromium over 0.1 mg/L … The abandoned mines are usually used for bathing purpose by those who are unaware of the potential threat of hexavalent chromium contamination. The Sukinda valley and the site of India’s largest chrome ore deposits ranks fourth worst polluted places in the ‘Blacksmith Institute Pollution Report for 2007’ … [which] says, chromite mine workers are constantly exposed to contaminated dust and water. Gastrointestinal bleeding, tuberculosis and asthma are common ailments. Infertility, birth defects and stillbirths and have also resulted. The Odisha Voluntary Health Association (OVHA) funded by the Norwegian government, reports acute health problems in the area. OVHA reported that 84.75% of deaths in the mining areas and 86.42% of deaths in the nearby industrial villages occurred due to chromite mine-related diseases. The survey report determined that villages less than 1 km from the sites were the worst affected, with 24.47% of the inhabitants found to be suffering from pollution-induced diseases” (Das & Singh 2023, p.7-8).

Search ‘iron ore mining Odisha occupational health’ jindal ➡️ “The occupational diseases and hazards do not reveal the actual situation and figures about the mines as the Performance Monitoring and Evaluation System are not carried out properly and also due to lack of qualified doctors in this sector” (Das & Singh 2023, p.11).

Now we have some circumstantial evidence that Gillette razor blades could contain chromium mined in the Sukinda Valley by Jindal, and that there are serious trade justice issues here relating to the duty of care that Jindal has for the people who work in, and live in the vicinity of, such a highly toxic workplace. This is one trade justice issue that we have found in this supply chain. There are other related trade justice issues, like the dispossession of tribal people’s land by the state and corporations to mine and process the valuable ores beneath. But we haven’t yet heard from the tribal peoples of the Sukinda Valley or any chromium miners. What’s their experience? How are they fighting back? That’s the next piece of detective work.

6. how are workers and activists responding to this trade injustice?

QUESTIONS: What do the people experiencing this injustice have to say about it? Why do they work in these places? What other choices do they have? How are they, and the people who live nearby, responding to this injustice?

This is where you try to find how people making your stuff experience the exploitations of trade injustice that you have found out about. They’re never going to be passive victims. Here we’re looking for the struggles, the protest, the resistance, more just worlds that are being fought for and brought into existence.

🕵 Suggested online academic source searches: ‘[ingredient found before] +/or ‘[site of production found before]’ +/or ‘[company found before]’ + ‘ethnography’ +/or ‘workers’ +/or ‘activism’ +/or ‘protest’; then follow-up searches using keywords you find in the results.

example

In the previous stage, we focused in on one ingredient in our Gillette razor’s steel: chromium whose ore – chromite – is mined in the Sukinda Valley in the state of Odisha, in India. We found that there have been lots of studies of the severe health problems caused by working in these mines and living in the surrounding area, and lots of studies of the tribal activism that has met this ‘development’ since it began. Workers, their families and communities are never just passive victims of trade injustice in any site of production. So let’s see if we can humanise our razor blades, put some life into them. Again, we have to look for independent sources, ideally local and international NGOs who have had a long-term presence, and/or academics who have done in-depth social science research, in the area and/or the journalists and bloggers who report what they do.

To begin with, it’s worth noting that the detective work we did to answer the previous question about trade injustice didn’t find any human stories. But it did point to the kinds of human stories that could be found through further research.

Search ‘iron ore mining Odisha occupational health jindal’ ➡️ “Social risks for [Jindal Steel & Power Limited] … manifest from the health and safety aspects of employees involved in the mining and manufacturing activities. Casualties / accidents at operating units due to gaps in safety practices could lead to production outages and invite penal action from regulatory bodies. The sector is exposed to labour-related risks and risks of protests / social issues with local communities, which might impact expansion / modernisation plans. Also, the adverse impact of environmental pollution in nearby localities could trigger local criticism. Some of the key initiatives taken by the company in this aspect include regular safety audits at all plant locations, identification of fatality risk potential conditions (FRCP) at the workplace and at colony premises by safety professionals, monitoring and closure of risk potential conditions through review and quarterly review of health and safety performance by the company’s safety performance review forum” (ICRA 2023, p.3).

Search ‘iron ore mining Odisha occupational health jindal’ ➡️ “Chromite mining in India is at a very critical juncture where workers and their organizations are facing problems like privatization, saving their jobs and there has been a stable decline in the employment in this sector due to mechanization and other cost-cutting measures. In the present day situation occupational safety has taken a lay back and workers have a Hobson’s choice of ‘No Jobs versus Hazardous Jobs'” (Das & Singh 2023, p.11).

So, it seems, people looking for employment in this part of India may not have much choice, and Jindal is at risk of criticism and protest from workers and local communities because of the environmental pollution caused by its mining activities there and by its ‘expansion / modernisation plans’.

Let’s try to flesh out what’s been described here. To do so, ideally, we would be able to find some in-depth (ethnographic) research with people living near, working in and protesting about Jindal’s chromite mine in Odisha’s Sukinda Valley. So let’s look for that first, on Google Scholar:

Search Google Scholar for ‘ethnography sukinda chromite workers’ ➡️ “[The] abundance of mineral wealth, along with its mountains and forests, coastline and rivers, land and cheap labour, makes Odisha the most coveted land. Always, the most ordinary people have risen up leading extraordinary struggles against big dams, mega steel projects and massive mining operations. It is their sacrifice that is called upon whether for building the temples of modern India at the dawn of independence or to keep step today with the march of the global economy. It would be no exaggeration to call the history of post-colonial Odisha the history of forced dispossession, state repression and resistance against it” (Padhi & Sadanghi 2020, p.1).

Search Google Scholar for ‘ethnography sukinda chromite workers’ ➡️ “[Mining] involves vulnerability to natural resources, questions people’s existence, identity, and livelihoods. Mining has a far-reaching impact both on nature and the populace. It destroys ecological balance and diverts resources from the needs of the poor and marginalized, which leads to further marginalization and impoverishment of such populations … However, this process of marginalization and impoverishment is not going unchallenged. The development process in which minerals and mineral extraction play a crucial role was once hailed as the panacea for all human pain and suffering; it is now in question … The environmental movements, anti-displacement movements, human rights movements, anti-mining movements, and tribal movements have all emerged as consequences and challenges to such development processes. The relationship between development and the mineral industry is providing context for the emergence of these movements” (Samal 2025, p.1).

So, as long as there has been industrial-scale mining in this part of India, there has been resistance to its injustices by the tribal people living there whose land was appropriated for these mines to be dug. So what has this experience been like for the Sukinda Valley’s tribal people?

Search Google Scholar for ‘ethnography sukinda chromite workers’ ➡️ “In the vicinity [of this ethnographic study] there are now many chromite mines like Kaliapani, Kalarangi, Saruabila, Sukurangi [see search below] and iron ore mines like Tomka. The area acquired and sold by the government to the industries is known as Kalinganagar Industrial Complex which is almost developed as a steel and metallurgical hub. A total area of 30,000 acres has been earmarked by the government for this purpose in 1992 … For this big development project the [tribal] Hos of Sukinda, the original inhabitant of this area were asked to evacuate their villages. Under the Land Requisition Act their lands were requisitioned. The first land acquisition was done in 1990-96 near Duburi. In exchange the people were promised a compensation package which included land for land taken, jobs in the industries, houses, and schools for children. The process of displacement and resettlement was not smooth at all and was marked by broken promises, violence and forceful evacuation of the Hos from their villages” (Mohanara 2023, p.293).

Before we continue, let’s check that Mohanara’s (2023) study included people living near the Jindal chromite mine. To do this, we copy the list of chromite mine names from the paragraph above into our browser search bar and add Jindal. The result is a letter from Jindal confirming that:

Search Google for Kaliapani, Kalarangi, Saruabila, Sukurangi and Jindal ➡️ ” Jindal Chromite mines … lease [an] area of 89 Ha located at Forest Block-27 and village of -Kaliapani, Tahasil-Sukinda, District-Jaipur, Odisha” (Jindal Stainless 2023, np).

Now we can be confident that this ethnographic study has been conducted with tribal people who, among others, live near the Jindal Chromium mine we’re concerned about. So we can read more about their experience of dispossession, resettlement, mine labour and the ‘modernisation’ and industrialisation of their land:

Search Google Scholar for ‘ethnography sukinda chromite workers’ ➡️ “The contemporary Ho society is witnessing a rise in number of people joining a variety of modern occupation. Due to rise in possibility for various non-traditional occupations, more number of people are earning cash on a daily basis or on a monthly basis. The different emerging occupational groups include the daily wage labour working in mines, the drivers and helpers in mineral transport, the salaried employee in the steel plants, and the salaried employee with the government” (Mohanara 2023, p.294).

Mohanara’s (2023) ethnographic research is interested in the ways in which the Ho people have negotiated tribal and Western understandings of health and medicine that have been thrown together by the industrial ‘development’ of their land. This is an interesting lens for us to understand how the pollution created by chromite mining is experienced and understood:

Search Google Scholar for ‘ethnography sukinda chromite workers’ ➡️ ” Working in mines without basic amenities and health facilities is like putting one’s life into risk of suffering and death. Both open cast as well as underground mining involves hazardous activities and the workers are vulnerable to suffering without adequate healthcare and insurance facilities. The change in occupation from a tribal subsistence farmer to a mining worker comes with a corresponding shift from pure to polluted workplace. We can see here how large scale socio-economic factors get translated into individual suffering … Further, this suffering is intolerable when it becomes meaningless” (Mohanara 2023, p.297-8).

So, the suffering experienced by tribal workers in Odisha’s chromite mines can ‘become… meaningless’. Let’s see if we can understand what this means:

Search Google Scholar for ‘ethnography sukinda chromite workers’ ➡️ “The [tribal miners, drivers, helpers, salaried corporate and government employees] prefer biomedicine to traditional medicine … There is a sense of enchantment towards the modern way of life that is happening around them. Use of modern medicine has enabled them to claim higher status in the society … Working in mines gives a sense of detachment from the Ho social structure as well as a sense of flexibility from the rigidity of traditional medical practices and beliefs. For treatment of any disease and illness the mines workers go to the raulia but also consider visiting biomedical personnel. The allopathic [Western medicine] prescriptions never require any relationships, social, ecological or super-natural, to be mended. Thus the spread of modern education, modern occupation and availability of allopathic medicine lead to the emergence of a concept of body impermeable to outside intangible influences. This is a new medical cosmology which is in conflict with the traditional Ho medical cosmology. Persons experiencing illness and undergoing healing process now face a disturbance in the earlier ontological framework. Ignoring the Ho concept of body and mind brings forth a situation in which people experience a state of meaninglessness leading to insecurity about their own ontology” (Mohanara 2023, p.294-5).

To illustrate this point, Mohanara (2023) includes a account of a Ho tribesperson who had experienced poor mental health by being stuck between traditional tribal and allopathic (Western) remedies. Unfortunately, for our purposes, there’s no mention of this person working a chromite mine or experiencing hexavalent chromium poisoning. So, we have to look elsewhere to humanise the chromium in our razor blades.

This seach was a bit convoluted. In the search results on Google Scholar for ‘ethnography sukinda chromite workers’ we found a paper called ‘Digging women: towards a new agenda for feminist critiques of mining‘ (Lahiri-Dutt 2012). In this, we found a reference to a book chapter called ‘Exploring the impact of chromite mining on women mineworkers and the women of Sukinda valley, Odisha: A narrative’ (Parthasarathy 2004). Because we’re interested in the chrome that could have been an ingredient in the razor blades we bought in 2025, a 2004 source is fascinating but not what we’re looking for. But it does mention two NGOs that Parthasarathy collaborated with at the time. One is called ‘mines, minerals and PEOPLE’. We check if it has a website. It does. We search it for ‘Chromite Odisha’ and there’s one hit – an story on an independent Indian news website called ‘The wire’ (Dash & Choudhury 2018):

Search ‘mines, minerals and PEOPLE’ website for ‘chromite Odisha’ ➡️ “Sukinda (Jajpur district, Odisha): Outside her mud-walled house, Pitayi Mankidia, 30, is holding her two-year-old daughter Huli, who is crying. Huli’s face is smeared with neem leaves to soothe the pain and itching that is aggravated by the dust in the area. Both mother and daughter have specks of blood dotting the rashes on their bodies. ‘Trucks keep passing every second without a break, the roads are broken exposing the bare earth. The dust never settles,’ Pitayi said, gesturing at the queue of loaded lorries outside her house. ‘It is difficult to breastfeed my children. I barely lactate these days.’ Pointing at one of her sons, Bablu, who is also affected with rashes – small beads of them all over his back – she adds, ‘This makes him too unwell most of the time to even attempt going to school.’ … This 20-km stretch is the country’s largest deposit of chromite, an ingredient of metallic chromium, used to make stainless and tool steels. It is also the world’s biggest open-cast mining area. Across the road from Pitayi’s home, the world looks very different. The Tata [another steel corporation] residential colony, built for employees, has parks, water-treatment plants, club-houses, supermarkets, schools and the only post office in the area. The Tatas also control the most essential facility for survival here: the hospital. The colony’s world-class living conditions are indicative of the class-apartheid that mining and capital have produced here. … Pitayi’s husband Biju Mankedia, working in a nearby minefield for a meagre sum of Rs 200/day, too, takes ill very often. His risk is even higher; he enters the mouth of those mining pits for as long as eight hours every day. The constant fatigue makes him unable to work for longer. He has dry, patchy skin in certain places, like fish scales, that itches and sometimes bleeds. Apart from a primary health care centre 35 km away, the Tata hospital is the only accessible one in the valley. The compact, single-storeyed structure, with only 30 beds and seven doctors, caters to about 40,000 people from 42 villages. ‘We had been to the Tata Hospital a few times and never recovered fully,’ Pitayi said, ‘Later, they asked me to have specialised treatment for which I had no money. We have been on home remedies ever since’ (Dash & Choudhury 2018, np).

What is disturbing and valuable about this account is that it shows how chromite mine workers and their families experience the pollution in their bodies, in their skin, and how they live with the illness and discomfort that this causes. But this account mentions Tata’s chromite mine rather than Jindal’s. So, the next task is to see if there a connection between the Jindal chromium that’s helping those Gillette Blades to give us a smooth shave and the health of Pitayi and Biju Mankidia and their son Bablu.

Search Google for ‘Tata Jindal chromite Sukinda valley’ ➡️ “Tata Steel Mining Ltd and Jindal Stainless Ltd signed an MoU to jointly unearth chrome ore locked up in the boundary between their mines located at Sukinda in Odisha’s Jajpur district, officials said on Monday. This initiative will help conservation of chromite ore which otherwise would have been left unmined forever, Jindal Stainless said in a statement” (Press Trust of India 2021, np).

So Tata and Jindal are mining the same chromite deposits in the Sukinda Valley. When we search Google Maps for ‘Jindal Chromium mine’, we can see a labelled satellite image that shows that ‘Tata Steel Sukinda’ is next door:

Now we have learned something about the ways that mine workers can experience and live with chromite poisoning, it’s important to find out if and how there is local resistance to this and other trade injustices for which Jindal has some responsibility. There is mention of resistance in sources we look at earlier:

Search Google Scholar for ‘ethnography sukinda chromite workers’ ➡️ “… the most serious threats from mining are those that challenge tribal rights to their culture and legacy … These conditions result in resistance to these mining projects by tribal, and gradually, it takes the form of a movement” (Samal 2025, p.2).

But how has this movement resisted the injustices caused where the chromium in our blades is likely to have been mined? What activism has taken place, where and by whom?

Search Google for ‘Odisha sukinda chromite mining activism’ ➡️ “As you move from Jajpur town towards Sukinda in Jajpur district of Odisha, the fields turn parched and infertile. Rusty, dust-laden leaves wilt silently from dying trees. Trucks pass by, leaving a trail of chromite dust that never seems to settle down. The working classes are busy going to or returning from work; mining ores, lifting weights, occasionally taking long breaths to inhale the air that could kill them. … Since independence, the annual production of minerals in Odisha has increased more than sixty-fold, yet 46 per cent of families in the state live below the poverty line, earning less than Rs 15,100 in a year. Seventy three per cent of Adivasis [original inhabitants] and 53 per cent of Dalits [‘untouchables’ or outcasts] in the state live below the poverty line. The National Mineral Policy 2019 defines minerals as shared inheritance by citizens of a state and mentions that the government is only a trustee on behalf of the people. This means, governments don’t own mines. Exploration companies (PSUs or private) don’t own mines. People own mines. Why then, are the Adivasis turned into starving, diseased, daily wage labourers on the mines discovered under their very own lands? The Mines and Minerals Amendment Act in 2015, directed that a District Mineral Foundation (DMF) be formed in every state that will act as a welfare fund, to be used for development of people and regions affected by mining operation. It mentioned that the high priority areas of spending will be drinking water supply, healthcare, environmental protection, education, welfare of women and children among others. The collection of the fund would be 10 per cent of royalty from auctioned mines (leases granted on or after 12.01.2015) and 30 per cent of royalty from mines allocated prior to 12.01.2015. Odisha has collected the highest amount in the entire country in its District Mineral Foundation, almost 12 billion rupees. However, the areas of spending of DMF are extremely problematic” (Biswal 2021, np).

The article was published on ‘India’s biggest rural media platform’ – the Goan Connection – and was written by ‘a medical doctor and public health researcher, currently exploring the causes and implications of health inequity across Odisha’ (ibid.). It describes how Odisha’s DMF fund was being spent not on healthcare, environmental protection, etc. but on an international hockey stadium, a recreational facility with a musical fountain and a children’s play area, power supply to an airport, police vehicles, 500 acres of guava trees. It expressed anger about another fund called the ‘Odisha Mineral Bearing Areas Development Corporation’ (OMBADC) which was directed by the Supreme Court to invest in ‘undertaking specific tribal welfare and area development works so as to ensure inclusive growth of the mineral bearing areas’ (ibid). According to activist Pridip Pridhan, it says, ‘only one per cent of total fund has been utilised for development of tribal people in the mineral bearing districts within four years. The remaining 99 per cent of the amount has been withdrawn and invested without legislative sanction’ (ibid.). It says anger is still simmering about the police shooting dead 13 people protesting the acquisition of land in 2006 for a Tata steel Kalinganagar township in Odisha state. This is the ‘Kalinganagar Industrial Complex’ mentioned earlier by Mohanara (2023). Biswal’s article ends with a sarcastic swipe at one of Tata’s ‘Corporate Social Responsibility’ initiatives:

“Tata Steel is launching a Green School Project to ‘teach’ the malnourished children of Sukinda about sustainability and environmental degradation, even as chromium flows in their water bodies and inside their tiny bodies in their veins” (Biswal 2021, np).

This article gives a detailed sense of the trade injustices that exist and are fought over, particularly the broken promises made by governments and corporations to use a slice of the considerable wealth these mines have generated from these tribal lands to invest in the health and wellbeing of the tribal inhabitants they dispossessed and displaced. So what protest, activism, resistance has been happening recently, maybe around the time that our blades’ chromium was mined?

Search Google for ‘Odisha chromite protest’ ➡️ “Today, over 1000 protesters, including women from Dhinkia, Niyamgiri, Khandualamali and other areas of protests, gathered in Bhubaneshwar protesting against the Make-in-Odisha Conclave [a state-sponsored investment summit] and the current anti-people Development Model of the Odisha government. The protesters resolved to continue all the ongoing struggles against the corporates in Odisha leading the loot of natural resources and destruction of the environment, and demanded an immediate stop to the continuous forceful displacement of people from their lands and livelihoods. We publish the full text of an open letter issued by mass movements in Odisha on behalf of Bisthapan Birodhi Jana Andolon Mancha (Odisha) questioning the Make-in-Odisha Conclave and the current development mode” (Anon 2022, np).

The letter begins:

“Respected Sir,

We as concerned citizens, social activists, political and human rights activists, environmentalists and journalists and the leaders of twelve mass organisations on behalf of Bisthapan Birodhi Jana Andolon Mancha, Odisha, appeal for the protection of natural resources and an immediate end to the continuous forceful displacement of people from their lands and dwelling places.

We express our protest and dissent against the Odisha government’s Make-in-Odisha Conclave in Bhubaneswar. Inviting more investments in the name of development will uproot the lives and livelihoods of people dependent on these land, forests and coasts. We appeal to your conscience to intervene and prevent the exploration and exploitation of natural resources through unmindful and unwanted mining of bauxite, iron ore, chromite, coal, river sand, china clay and other resources in the name of development. People are struggling against all odds and hardships to protect the same for future generations even as they remain deprived of access to basic needs like education, health and nutritional food security. …

Mining of different ores and mineral deposits has increased exponentially since the year 2000. Huge expanses of mines and minerals have been explored and exploited legally and illegally … As per the provisions of PESA of 1996, Forest Rights Act of 2006, Forest Conservation Act of 1986 and regulation of 1956 Act of Odisha government with new amendment in 2000, there cannot be transfer, acquisition or forceful takeover of natural resources without the consent of Gram Sabha [the local democratic system]. However, the Odisha government and its administration do not honour the said laws as they hand over mines and lands to corporate houses. In countless instances, district administration does not follow the legal process in public hearings for environment clearances or the Land Acquisition Act, 2013. Local communities across districts in Odisha have been witness to irresponsible, corrupt administrations using police force to repress peaceful, democratic people’s resistance when they voice their concerns. The hijacking of public hearings through police force in order to impose destructive projects over people’s lives is blatantly undemocratic and unconstitutional” … (Anon 2022, np).

This detective work has provided us with some circumstantial evidence of the ways in which the mining of chromite by Jindal and other corporations in Odisha’s Sukinda Valley continues to affect the health of the tribal peoples who were dispossessed and displaced from this land and have ended up working in the mines. We have found an account of one family’s suffering from chromium poisoning through exhaustion and skin rashes, and an ethnographic study of a clash between tribal and Western medicine that can lead to this suffering feeling meaningless. We have found arguments about broken promises made by corporations and governments in the course of ‘developing’ this land. These promises involved sharing the wealth generated from mining in order to improve the health and wellbeing of the dispossessed tribal people. We have found claims of widespread illegal activity behind this dispossession and the mass deforestation that has been caused by open cast mining. We have found histories tribal resistance and repression that continue into the present day. We can be confident that our razor blades are full of this life and struggle. The next task is to see who’s putting pressure on governments and corporations closer to home to ensure that our razor blades’ supply chains can function more ethically and sustainably; to ask if that pressure could help to give the tribal activists the justice they are demanding; and to wonder how the evidence we have gathered through this detective work could add – even in only a small way – to this pressure.

7. What can you do with your findings?

QUESTIONS: Who, closer to home, is putting pressure on the relevant corporations and governments to address the trade injustices you have found? How can the findings of your detective work contribute to this? Are you the only person who can act on what you have found?

‘Follow it yourself’ detective work pops the bubble of commodity fetishism, attempts to join the dots between heres and theres, selves and others, and can challenge your understandings of right and wrong, blame and responsibility. This task isn’t designed to make you feel guilty and to shop differently. If you think what you have found is wrong and needs to change, it’s important to find out what levers exist that you can help to press a little harder maybe.

🕵 Suggested online academic source searches: ‘[your corporation or brand} + ‘boycott’ +/or ‘CSR’ +/or ‘Multistakeholder initiative’ +/or ‘CSDDD’; [your chosen commodity] + ‘ethical’; then follow-up searches using keywords you find in the results.

example

We started this task with a blissfully ignorant act of consumption. Some razor blades were getting blunt, and shaving was becoming uncomfortable. A quick visit to a local supermarket – and £20 – solved the problem. A pack of eight new razor blade cartridges for a Gillette razor had been bought. They’re sitting in a bathroom cabinet, waiting to be used. Now, after doing this detective work, it’s time to reflect on who and what this act of consumption now seems to involve, and to think through your options about what to do about it.

Follow it yourself detective work pops the bubble of commodity fetishism (the idea that commodities exist only in and of themselves, without connection to the people who made them). And joining the dots with people experiencing trade injustice in your chosen commodity’s supply chain can create what’s called ‘cognitive dissonance’:

“When one learns new information that challenges a deeply held belief, for example, or acts in a way that seems to undercut a favorable self-image, that person may feel motivated to somehow resolve the negative feeling that results—to restore cognitive consonance. Though a person may not always resolve cognitive dissonance, the response to it may range from ignoring the source of it to changing one’s beliefs or behavior to eliminate the conflict” (Psychology Today nd, np).

One of the problems with popping the bubble like this is that it can start a thought process in which other bubbles get popped. Dozens, hundreds of them! We found a paper in which a doctor had travelled a similar path to ours. It changed the way he saw the world he was living in:

“I discovered that it is not possible to ignore the impact of mining on daily living. I own a house, a car and a mobile phone, and all are dependent on mining. In my house, various components arise from mining: the bricks come from clay while the attractive chimney breast is made from local slate. Nails and screws are either iron or zinc, while water pipes are made from copper, zinc, nickel and chrome. The window glass needs silica, feldspar and soda ash for its genesis, while the concrete base supporting the house consists of limestone, clay, shale and gypsum. Locks and hinges are also made from copper, zinc or iron, and the insulation is glass wool (silica, feldspar, soda ash) or expanded vermiculite. Without the following mined essentials, the car would not function properly: glass (as above), battery (lead, zinc), paint (cadmium), steel (an alloy of iron and other metals) or aluminium, while under the bonnet there is a whole mix of elements, including nickel, copper, molybdenum, beryllium, vanadium, as well as a mineral (mica). And my mobile phone contains gold coating the wires on the circuit boards (possibly the only gold I own), copper acting as a transistor in the circuit boards, tantalum to store electricity in the circuit boards, rare earth elements to provide colours and tungsten to help the phone vibrate. To take only one example, tantalum is used by many industries and manufacturers in capacitors. It takes about one tonne of rock to produce 30 grams of tantalum. Most tantalum comes from Central Africa, much of it being panned from ore in the Democratic Republic of Congo by small-scale miners. The trade is under the control of militia groups who rule by murder, rape and brutality. Smuggling of the element is undertaken to avoid sanctions and tax, leading to exploitation and corruption … Not a healthy lifestyle” (Stewart 2020, p. 1154).

One of the most common reactions to finding that your everyday life is connected to injustice is to feel guilty about your consumption (you bought the ‘wrong thing’), and to reduce that guilt by not buying that again (maybe letting the hair grow and grow) and/or buying better (is there an ethical alternative?). But you’re just one person, maybe the only person who has made the connections that you have made through following this thing. So, the first task is to find what other people closer to home know and are doing about the trade injustices that you have found.

Let’s start buy seeing if anyone has stopped buying Gillette razor blades for ethical reasons:

Search ‘boycott gillette’ ➡️ “Gillette faces backlash and boycott over ‘#MeToo advert’. … The razor company’s short film, called Believe, plays on their famous slogan ‘The best a man can get’, replacing it with ‘The best men can be’. The company says it wants men to hold each other ‘accountable’. Some have praised the message of the advert, which aims to update the company’s 30-year-old tagline, but others say Gillette is ‘dead’ to them. … People such as Piers Morgan have said they will boycott Gillette because of the message of the new advert. … [But Proctor & Gamble president Gary Coombe said:] ‘We knew that joining the dialogue on ‘Modern Manhood’ would mean changing how we think about and portray men at every turn. … Effective immediately, Gillette will review all public-facing content against a set of defined standards meant to ensure we fully reflect the ideals of Respect, Accountability and Role Modelling in the ads we run, the images we publish to social media, the words we choose, and more. For us, the decision to publicly assert our beliefs while celebrating men who are doing things right was an easy choice that makes a difference” (Baggs 2019, np).

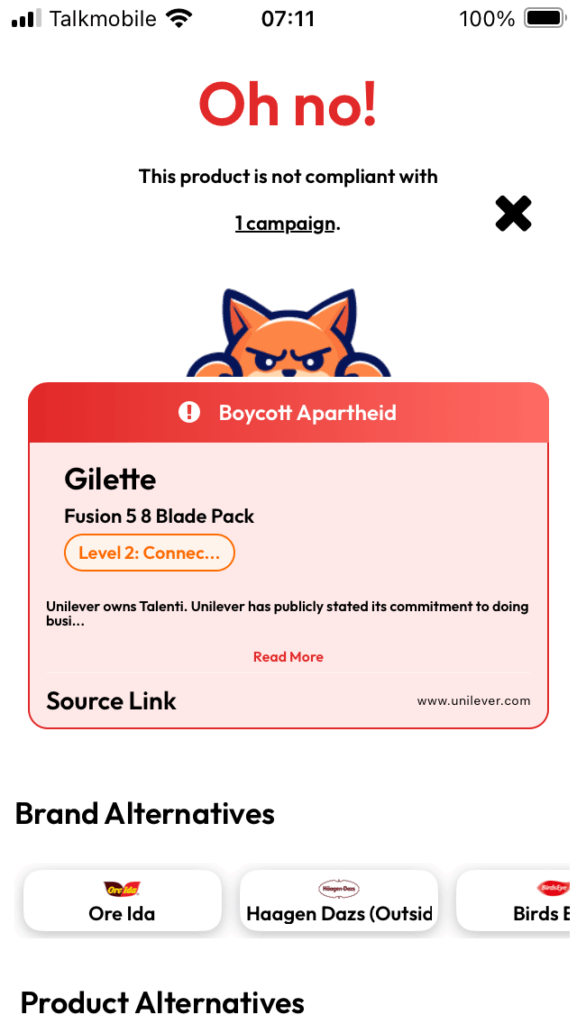

So Gillette has been boycotted by some men for its criticism of, and unwillingness to promote, toxic masculinity. In the literature, this advertising technique is called woke washing. These ‘ethical’ initiatives are unlikely to help chromite miners and displaced tribal people in India with their toxic problems. So let’s find out if there are other Gillette boycotts. You can download a phone app that lets you scan commodities’ barcodes to see if anyone has called for them to be boycotted. Let’s try the one called Boycat.:

This boycott is about Proctor & Gamble’s connection to Israel and is a boycott called for by the Palestinian ‘Boycott, Divestment & Sanctions’ (BDS) movement. The ‘brand alternatives’ that the app suggests don’t have a connection to Israel. Again, this doesn’t seem to be a boycott that will help chromite miners and displaced tribal people in the Sukinda Valley in India. And we haven’t found any evidence that Sukinda Valley activists are asking consumers to boycott products containing their chromium. As a general rule of thumb, it’s not a good idea to boycott brands unless the people affected by that boycott are asking you to do so. So let’s try another approach.

Let’s see of there more ethical and environmentally friendly razor blades that don’t include as an ingredient the poisoning of the people living where their ingredients are mined:

Search Google for ‘ethical razors’ ➡️ “9 best environmentally-friendly razors for a clean shave. … Razor blades are meant to be changed frequently, which means waste quickly adds up, not to mention the handles, too. Opting for a razor that lasts a long time (and actually looks nice enough that we want to hold onto it for years), and one that can be recycled, ideally blades and all, is a great alternative” (Borny 2025, np).

Search Google for ‘ethical razors’ ➡️ “Over the last decade or so, most of us have arrived at something you could comfortably call eco-conscious. You’ve only got to walk down the high street to notice it – people are swigging ice-cold water from reusable bottles, we drink our morning lattes from the same old reliable vessel every day and fast food restaurants no longer dish out fistfuls of plastic straws. Some people have campaigned vocally against unnecessary waste for years, others have had to be dragged kicking and screaming away from their single-use habits; but the one thing we’ve all got in common is that the sight of trapped sea life and plastic-choked oceans in Blue Planet II was enough to put us off our old ways for good. … The Xtreme 3 Bamboo Hybrid Razor offers a completely guilt-free shave, whatever your style. With a recycled and recyclable handle and packaging, it barely leaves a footprint on the environment, while offering all the powerful performance and precision-engineered design that you’d expect from Wilkinson Sword” (Wilkinson Sword nd, np).

The ‘completely guilt-free’ shaving options that are on offer seem only to involve minimising waste. Consumers are being asked to care about what happens to a razor after it’s purchased. So, these ‘ethical’ and eco-friendly razors won’t resolve feelings of guilt you may have about the people whose dispossessed and polluted lives are part of their production. As consumers, it doesn’t seem like we have leverage to resolve any cognitive dissonance we’re experiencing by shopping differently.

Fortunately, there’s more to life than consumption. This is where we turn to the philosopher of trade justice activism Iris Marion Young (2003). She has argued that feeling guilty about buying things made by exploited people isn’t the best way to motivate effective action. Guilt is individualised, it’s internalised, and it’s backward looking. It’s a feeling of responsibility for something bad that happened in the past. What can you do about that?! A more effective response, she argues, would be to externalise those feelings, work through them with other people feeling the same way, and to direct them towards shaping a more just future by acting in solidarity with supply chain workers and the world they want to bring into existence. This means, in the case of our razor blades, finding ways to act in solidarity with Sukinda Valley’s mining activists. We found in the previous step that they want the mining corporations and their government to deliver what they promised. They want to change corporate and government behaviour by holding them accountable for the promises that they made about the sharing of mining wealth. And they want them to stop destroying more forests and livelihoods by expanding their mining and steel-making operations.

How you can act in solidarity with protests in a particular part of the world depends very much on where you live in the world, the power you have to change the behaviour of corporations and governments (as a teacher, a researcher, a student, a supply chain worker, an executive, a politician, an activist, a journalist – anyone can do this task), and the economic, social and cultural capital at your disposal (the more we research this topic only in English, the more we realise the limits of our understanding). Whoever you are, wherever you are, let’s try to keep focused. Let’s get back to those razor blades and the company that made them. That’s what’s helpful about the ‘follow the thing’ approach. The thing helps you to focus on what to do next. Your enquiries are always involve it.

So, let’s ask another question: what responsibilities does Gillette (and its parent company Proctor & Gamble) have for what’s happening in the places where they source the rolls of martensitic stainless steel that they make into razor blades? This is where we get into labour rights, transparency and sustainability legislation, the creation and policing of which is one of the main goals of the trade justice movement (Trade Justice Movement nd). We have been reading about one of the newest – The European Union’s ‘Corporate Sustainability and Due Diligence Directive’ which came into force in July 2024 – and wanted to find if this could help. It looks promising:

Before we could get to it, however, we found a huge patchwork of regional, national and international guidelines and legislation trying to press corporations to take responsibility for – and to remedy – exploitation in their supply chains:

Search Google for ‘what is the EU CSDDD?’ ➡️ “International soft law standards: Supply chain sustainability standards have undergone important changes during the last years. … The United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) provides a list of substantive principles for [multinational enterprises], comprising the areas of human rights, labour, environment and anti-corruption. The UN Guiding Principles (UNGP) on Business and Human Rights focus on human (including labour) rights-related principles, and in operationalizing those principles, by means of States’ duty to protect human rights (Pillar I), corporate responsibility and due diligence (Pillar II), and States’ duty to provide access to remedies (Pillar III). The UNGP explicitly contemplates corporations’ duty to exercise ‘human rights’ due diligence’ across their ‘value chains.’ However, these are not self-standing standards. They aspire to be ‘social norms’, and thus depend on voluntary compliance by corporates, and on the support of legal norms. Another key set of standards are the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises … The OECD comprises 38 rich countries (the Guidelines are adhered to by other countries) which are the domicile for a majority of the largest multinational companies. Their 2011 update incorporated a chapter on human rights and due diligence, to align with UN Guidelines; the 2023 update included climate change and biodiversity. The text is more detailed than the UN Guidelines. However, the OECD Guidelines too rely on voluntary commitments or outside enforcement. In contrast with the UN Guidelines, though, the signatory states commit themselves to set up National Contact Points (NCPs) to handle grievances, although States have flexibility in setting up the NCPs, and the grievance procedure is not ‘enforcement’, but complaint handling and mediation. Soft law, industry-wide and unilateral voluntary commitments have often failed to deliver clear, convincing and durable improvement in supply chain sustainability. This is why the UN established in 2014 an open-ended intergovernmental working group on transnational corporations to elaborate an international legally binding instrument. The current draft refers expressly to ‘human rights due diligence.’ However, as a global instrument, its chances of being adopted (and ratified) soon are not high. National standards: Different jurisdictions have ramped up efforts to adopt their own standards. Progress is undeniable, but patchy. Some countries were forerunners, like Brazil, with its Dirty List of employers that failed to prevent forced labor and similar practices and were excluded from public contracts. Then, the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act of 2010, the UK Modern Slavery Act 2015, and the Australian Modern Slavery Act of 2018 exemplified a first generation of ‘supply chain’ statutes, with a ‘disclosure based’ and ‘narrower’ approach, focused on slavery and forced labor. This was mirrored by more recent initiatives, like the Canada Fighting Against Forced Labour and Child Labour in Supply Chains Act, of 2024, or the New Zealand proposed Modern Slavery Reporting Bill. Other jurisdictions have maintained a ‘disclosure-based’ focus, while encompassing environmental matters, such as the Swiss Code of Obligations in 2022, or the proposed measures in New York for a Fashion Sustainability and Social Accountability Act, or India’s SEBI consultation on ESG Disclosures, Ratings, and Investing. ‘Conduct’ legislation is less common. Brazil’s blacklisting system seeks to change conduct indirectly (blacklisting). The US Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act may be the strictest supply chain legislation, with an outright import prohibition, and a requirement of certification, but also the narrowest, focusing on goods manufactured totally or partially with forced labor in China, especially in the Xinjiang region. The main examples are the French Vigilance Law and the German Supply Chain Act. The European Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) follows in their steps” (Muñoz 2025, p.3-5)

With this as the wider content, we then started digging a new rabbit hole looking for softer and harder legislation that could address the mining-related trade justice issues that tribal and other people were protesting about in the Sukinda Valley. Knowing about legislation, as the Sukinda Valley protesters do, can allow concerned citizens to hold corporations and governments accountable to the standards of behaviour that they have promised. We found that Gillette’s ‘corporate social responsibility’ policies seemed to be based on supporting projects that tried to combat toxic masculinity and that supported community projects in the Global North (Gillette ndb). We found that Gillette’s parent company – Proctor & Gamble – could be at risk from its investors wanting to invest elsewhere because of extra costs (and potential fines) related to the ‘European Union Deforestation Regulation’ (EUDR). This insists that corporations know and show that any ‘forest-risk’ commodities that they import into the EU have not been produced on deforested land. We wondered if this included land deforested to mine chromite, but the regulations’ list of ‘forest-risk’ commodities are all agricultural (GTRI 2023, Haill 2023, Sutherlin 2024). When we searched for Indian criticism of the EUDR, we found a source that mentioned another piece of EU legislation that was affecting the Indian steel sector: the ‘Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism’. This was designed to decarbonise the international steel industry by putting financial pressure on coporations exporting steel to the EU – like Jindal – to produce ‘green steel’ (Ross 2024). But, again, we couldn’t see how this could help to address the concerns of the Sukinda Valley protestors. That steel would still need chromium to be sourced in order to make the steel used in Gilette’s razorblades. We then turned – at long last – to the CSDDD. What was it promising to do?

Here’s a quick summary. The CSDDD applies to EU- and non-EU-based companies with a turnover of at least EUR450 million within the EU and and/or with at least 1,000 employees (like Proctor & Gamble?). It requires them to have human rights strategies in “relevant business processes [and] procurement strategies” along with “training and risk control, verification strategies, contractual assurances and controls (on prevention)” (Muñoz 2025, p.10). They are obliged to “identify, analyze and prioritize actual or potential harms, prevent and mitigate, [and to] include notification mechanisms, and ways to monitor the effectiveness of due diligence measures” (ibid). The CSDDD applies to each company’s “chain of activities” including extraction, sourcing and manufacture (e.g. of chromite to make martensitic stainless steel?) within and beyond the borders of the EU (e.g. in India?), and not only by those companies but also their subsidiaries and direct and indirect business partners (e.g. like Jindal?). The CSDDD focuses in particular on human rights and environmental due diligence, legally mandating companies, their subsidiaries and business partners to adhere to the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (which have so far been ‘soft’ guidelines). The CSDDD looks promising for the Sukinda Valley protestors because:

Search Google for ‘Indian criticism of csddd’ ➡️ “[Its] recitals state that human rights are ‘universal, indivisible, interdependent and interrelated’; and that the Directive’s aim is to ‘comprehensively cover’ human rights. They also indicate that ‘[d]epending on the circumstances, companies may need to consider additional standards’, and make express reference to ‘intersecting factors’, and to the circumstances of indigenous peoples, and discrimination against women” (Muñoz 2025, p.12-13).