followthethings.com

Back to school

‘What would you say to the person who made your … ?’

A ‘pop the bubble’ icebreaker task for trade justice education

Selected poscards from our wesbite’s launch at the Eden Project in 2011 in slideshow above.

If you’re starting out some trade justice education – at any level, and with any students or public you would like to engage – it’s important to assume that they may already know and care about the issues you want to address. A simple way to find out is to a) encourage them to think about a commodity that’s important to them and then b) ask them what they would say to someone working in its supply chain if they had the opportunity. We have written about a couple of times when we have done this – when we launched followthethings.com in the Tropical Biome at the Eden Project in 2011, and when we were invited to introduce trade justice to a class of primary school students in Exeter in 2015. In both cases, this task needed a good prompt. At the Eden Project, the prompt was the Eden Project – the Tropical Biome was stocked with plants that are the sources of everyday commodities and their labelling and the design of the space made these connections. So we set up our card writing station to catch people as they walked by. In the primary school, the teacher asked the students what their favourite foods were, CEO Ian did some ‘who made my stuff?‘ research on a few, showed the class his findings, and the students were tasked to write to a corporation or supply chain worker that was mentioned with their thoughts. There’s always the option, if the writers (and their parents / guardians where appropriate) give their permission, of making this writing public, posting it online, tagging the corporations, asking for replies. The aim of this task is to gently ‘pop the bubble’ of commodity fetishism in order to encourage an appreciation of the work that has gone into making the things that people love to eat, wear and buy. This summary may be enough for you to try this for yourself. But we’ve also re-published a couple of blog posts below about our experiences of trying this out for ourselves.

Page reference: Ian Cook & Joe Lambert (2025) ‘What would you say to the person who made your … ?‘ followthethings.com/what-would-you-say-to-the-person-who-made-your.shtml (last accessed <insert date here>)

Estimated reading time: 19 minutes.

a) ‘what would you say to the person who picked the banana in your lunchbox?’

by Ian Cook

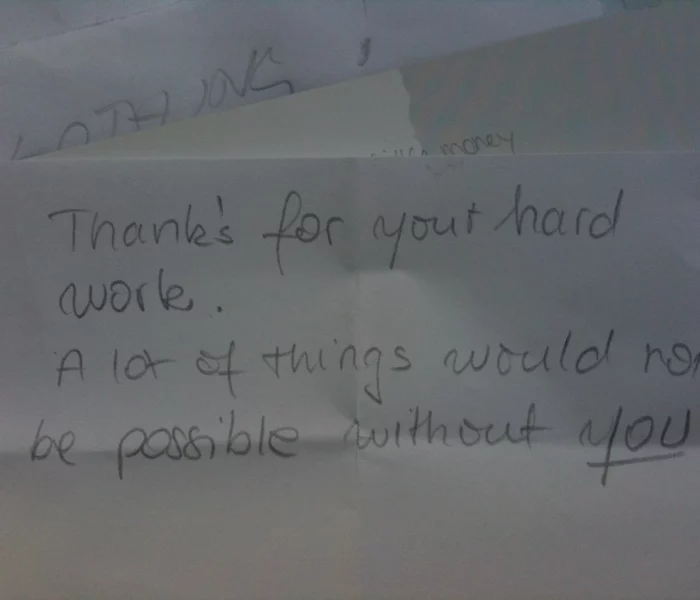

Thanks for your hard work. A lot of things would not be possible without you!

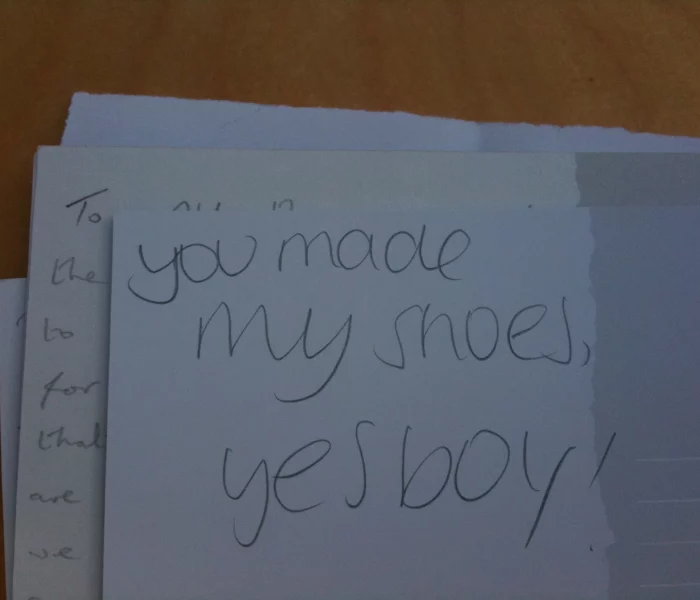

This is just one of the touching personal messages written by Eden Project visitors during 2011’s Harvest Festival week. Three Exeter University students and I set up a stall by the smoothie stand in the Humid Tropics Biome. We talked to passers-by about the plants that they had seen that day. ‘Which ones had produced ingredients for your clothes, shoes, lunch, anything you have with you?’ ‘Imagine a person who had, for example, picked the cotton in your top, tapped the rubber in your shoes or packed the banana in your lunchbox.’ ‘What would you say to her or him, if you had the chance?’

Almost everyone stopped to talk to us. Many said that they hadn’t thought much about this before. We provided postcards and pencils, and people spent time talking with their friends and family about exactly what they should write. We collected the cards. At the end of the day, we had 160 heartfelt, friendly and sometimes humorous messages.

Among them were:

Sorry that you earn so little money. Thank you so much for doing that. Hope you have a better life because of me buying your things.

Thank you for growing and picking the cotton to be made into the comfortable clothes I wear.

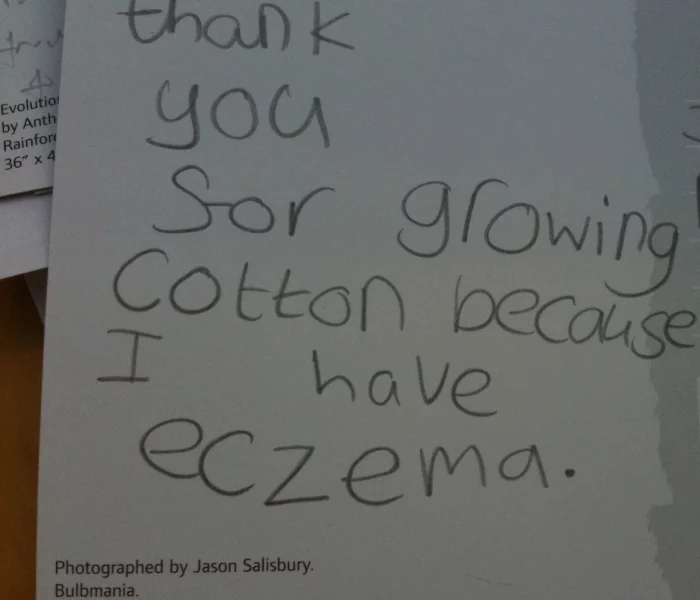

Thank you for growing cotton because I have eczema.

This is a small thank you. I will try and remember you and all like you whenever I put my shirt on.

I am wearing an Eden Project t-shirt made from organic cotton. I would like to know how much difference the Eden Project has made and whether selling to Eden has improved working conditions for the workers.

To the makers of basketballs, thankyou for successfully making something that bounces. They are very good!

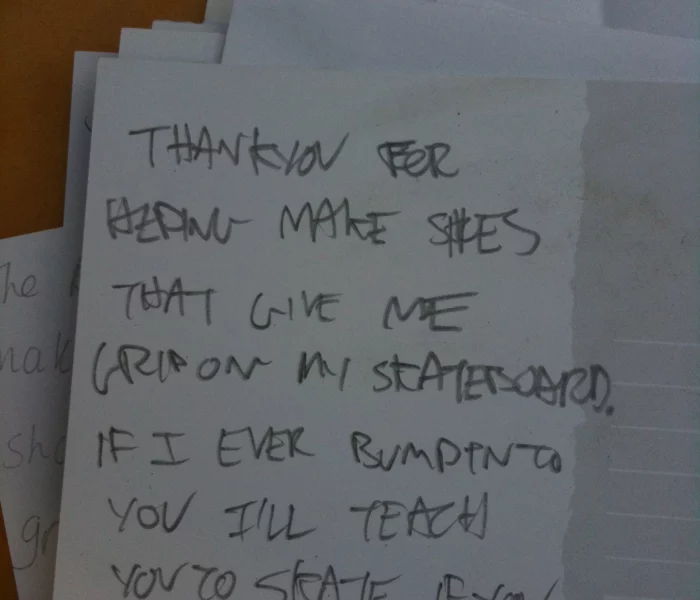

Thankyou for helping make shoes that give me grip on my skateboard. If ever I bump into you I’ll teach you to skate if you like.

I hope you have nice conditions in your rubber farm. If not I apologise for our wasteful society, and hope you know that at least this one pair of shoes will be loved and lived in for a very long time.

Are you happy?

That spot among the banana trees, coffee bushes and sugar canes was great for getting people thinking and talking about the ways in which the travels of things connect the lives of people. What we tried to do there was part of a much larger project. It’s focused around a ‘shopping’ website called followthethings.com. …

… in [its] Grocery [department], you could click on the fresh papaya [soon], and find an academic paper that I wrote in 2004 called ‘Follow the thing: papaya’. This is what ultimately brought me to the Eden Project’s humid tropics biome, encouraged me to put this website together, and sparked me to question what we might say to the people who make the things we buy. I did my PhD in the early 1990s when the range of tropical fruits on UK supermarket shelves was starting to expand. All of the papaya on these shelves were grown in Jamaica. So I spoke to supermarket executives and importers in the UK, and to government officials, farm managers, foremen, pickers and packers in Jamaica. I spent 6 months working on one farm, spending long hours talking with packing house workers, washing, grading, wrapping and boxing the fruit with them. …

The way that they helped to get thousands and thousands papayas, of uniform size, quality and price from farm to shelf was a complex and often fraught business. Nothing seemed to be straightforward. Nobody along this commodity chain seemed to have a detailed sense of how its various parts worked together. They kept asking me! Everyone admitted partial responsibility, but nobody ultimately responsibility, for the farm workers’ increasing poverty and hardship. This was supposed to be Jamaica’s post-sugar, post-plantation, post-colonial export agriculture. It was. But also it wasn’t. The past was alive and present in the ruined plantation buildings at the centre of the farm, and in the conflicts that occasionally erupted between pickers, packers and their bosses. Meanwhile, these fruits were being marketed in the UK as products of some tropical paradise, where the fruit just fell from the trees.

This experience convinced me that stories of lives and trade shouldn’t be over-simplified. There was no straightforward right or wrong, cause or effect, supply and demand, ‘do nothing’ or ‘do something’ story to tell. When I returned to the UK, I went back in to the supermarkets, and looked for the papayas picked, packed and shipped by the people I had met. They looked and felt very different to me, now. They had much more ‘life’ to them. So, I wondered, how could I encourage people who read my research papers to appreciate papaya – or any commodity for that matter – in the way that I had learned to appreciate them? How could I write about what I had learned in ways that might grab people, stick in their imaginations, provoke thought and discussion, have the same effect on them that it had had on me?

Researching with my students the … examples showcased on followthethings.com has begun to address these questions. The ways in which different examples try to encourage deeper appreciations of global trade via courtroom drama, cartoon humour, reality TV …, fake websites advertising things that should but don’t exist (a ‘conflict free’ iPhone?), and many more, is fascinating and important. Now that there’s so much user-generated content on the internet, the effects of this work on its audiences is much easier to appreciate. By putting in one place these examples and what’s been said about them, we hope that followthethings.com will inform and encourage discussions about trade justice in schools, universities, and plenty of other places, as well as informing and encouraging new following work not just by filmmakers, artists and academics, but by anyone with a computer and broadband connection. FIY: follow it yourself…

The postcards in the slideshow at the top of this post were collected from visitors after followthethings.com CEO Ian took part in the Eden Project’s Harvest Festival events on Sunday 2nd October 2011 with students Jack Parkin, Maura Pavalow and Alice Goodbrook. A shorter version of this text was published on the Eden Project Blog on 9 October 2011: here.

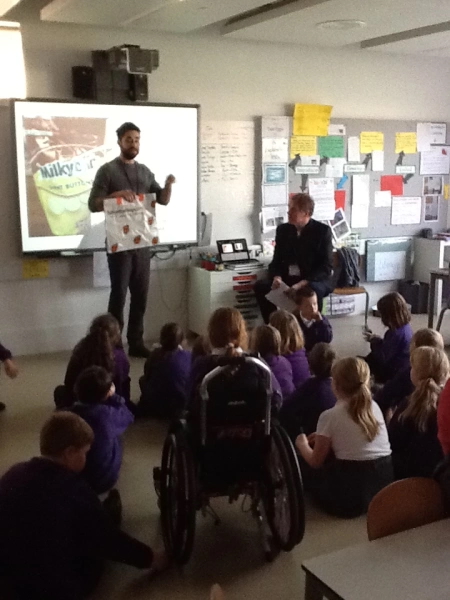

b) Milkybar buttons & child slavery: primary children write to Nestlé

by Joe Lambert

In December 2014, followthethings.com CEO Ian was contacted ‘out of the blue’ by Joe Lambert, a trainee teacher at Montgomery Primary School in Exeter who had been an undergraduate Geography student at Exeter University, where Ian works and where followthethings.com is based. Would Ian be interested in working with him and the school’s 7-9 year old (Year 3 and 4) students, who were following food the following month? Yes was the answer. Here’s what happened, as described by Joe.

After hearing geography was the key focus of the first few weeks of the January term, my ears immediately pricked. A geography graduate rarely gets an opportunity to use his degree but when he does you know he is going to relish it! My interests were further stoked when the topic was narrowed to identifying where does our food come from? This was the wonderful, crystallising moment when you realise maybe paying attention in the 1st year of your degree was worthwhile.

Initial ideas and reasoning for project

I know that from my own experience of primary geography it was very rare to stray too far from colouring in maps, however I feel this massively undersells what the subject has to offer for children Geography has a fantastic way of stripping a subject back to its rawest elements and exposing some of the funny, provoking and painful truths of human life. Although these truths may be uncomfortable, they can stimulate powerful reactions, reactions that can motivate, inspire and change. As a PGCE student I strive to create innovative learning experiences for children that will be memorable. Experiences that will promote discussion, result in interesting work but most importantly leave the children with a message. Using the topic of researching food as a jumping off point, I looked to extend the children’s knowledge of food production past a rudimentary understanding of where it comes from and onto the undeniable human experience of food manufacturing. It seems as though the rest of the world viewed this topic as too controversial or upsetting for primary aged children to be learning as the amount of online resources available were scarce. I, however, disagreed (see Barlow 2012). Children have a natural propensity for empathy and are unburdened by cynicism, allowing them to express true emotional responses to harder hitting topics. By showing children this kind of content, I hoped to produce emotive thoughts and reactions that could be recorded and shown on a wider platform. When I initially approached Ian with the idea of adapting the ‘follow the things’ approach for a primary-aged audience, I thought it was a bit of a pipe dream. The followthethings.com website includes lots of teaching resources and ideas for secondary school use, but nothing for primary. So I held a glimmer of hope that he would want to develop the thought.

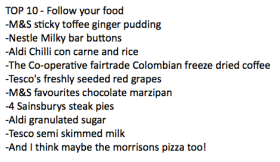

Getting things together

Ian and I met up and we hashed out some basic ideas for the project. After talking about the lack of primary aged resources for food production, we agreed that children deserve to now the truths about their favourite foods. So we feverishly got to work. The idea was simple, I, as a class teacher, would provide the children with the followthething bags, with the proviso that they bring into school the most exciting packaging from food they could find (Fig 1). Whether this was because it had come from far away or because it had a Fairtrade label on it, it didn’t matter because the tasks intention was to get the children to become food detectives and excited about tracking their food. The next step was to compile all the packaging and create a list of the 10 most exciting (Fig 2). Ian would then research these products and expose some of the darkest secrets of the foods production, revealing all to the classes later in the week. With these shocking secrets uncovered, the children would be tasked with writing a response to the people involved in creating their food (Fig 3). This could be a postcard to a supermarket giant or to a 9 year old boy who works on the cocoa plantation. The intention was to harness children’s natural sympathies and utilise them as a tool for emotive writing.

Teaching the lesson

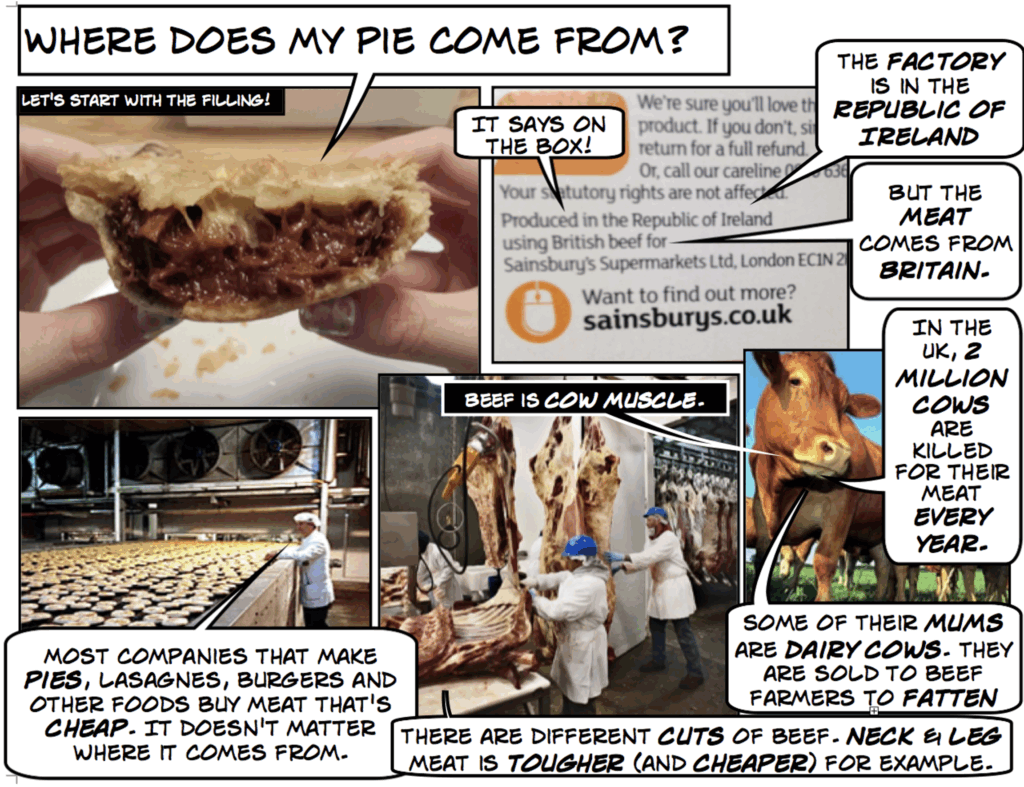

Ian hurriedly went to work on the list, researching over a few days the human and other stories in MilkyBar buttons, Tesco’s milk and the humble Sainsbury’s steak pie. We both felt that these three followings had a logical flow and worked nicely together with lovely similarities and contrasts, which would sponsor feelings of empathy, anger, happiness and disgust. For the buttons, Ian talked about child slavery in the cocoa field of the Ivory Coast and how Nestle and other companies ‘may have tolerated child slavery on cocoa farms to keep production costs low’. For the milk, he talked about farmers in the UK being paid less for their milk thank it costs to produce. And for the pie, he talked about the horsemeat scandal and how processed cow parts end up in other foods – including sweets – in unexpected ways . The research Ian did showed the children that food production isn’t a humanless endeavour and there are real lives involved in producing your favourite chocolate buttons.

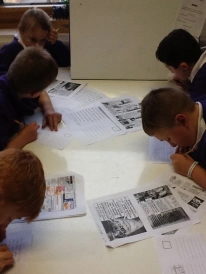

We worked with four classes of Year 3 and 4 children. After Ian talked and the children’s questions were over, I asked them to sit at the tables and think about writing a postcard to Nestle, Sainsbury’s, Abdoulaye the cocoa worker, or anyone else that Ian had talked about. Given what I has told them, what did they want to say or ask? By 3 o’clock, surrounded by 120 postcards, Ian and I had the unenviable task of sorting through lots of fantastic writing and picking out a selection to publish here on the followthethings.com.

Legibility was the initial acid test , but as we explored what the children has written we were surprised by the vast range of responses to the same ideas. It was wonderful to see the names of children, who usually struggle to find the impetus to write, on some of the most well thought out, sensitive pieces of work. We ended up choosing cards that, read in sequence, produced a kind of narrative arc. Even from something as innocent as a Milkybar button, we received a multitude of responses and reactions. It was really inspiring to see children so passionate and genuinely concerned for the wellbeing of someone they had never met before. It confirmed my belief that children have a natural inclination to be empathetic and that by exposing them to these strong emotional topics, they can produce some amazing work. Ian published on Flickr three series of postcards written by the children.

i) Milkybar Buttons

Here’s the first, where the children were expressing their concerns about child slavery in their chocolate.

e.g. To the people that make nastle. Thanks you for making are chocolate. keep up the good work. Me and grace think it is delicious. Well done for making this chocolate. From Kodie + Grace 🙂 PS make sure teh chocolate is fairtrade and it will taste even better.

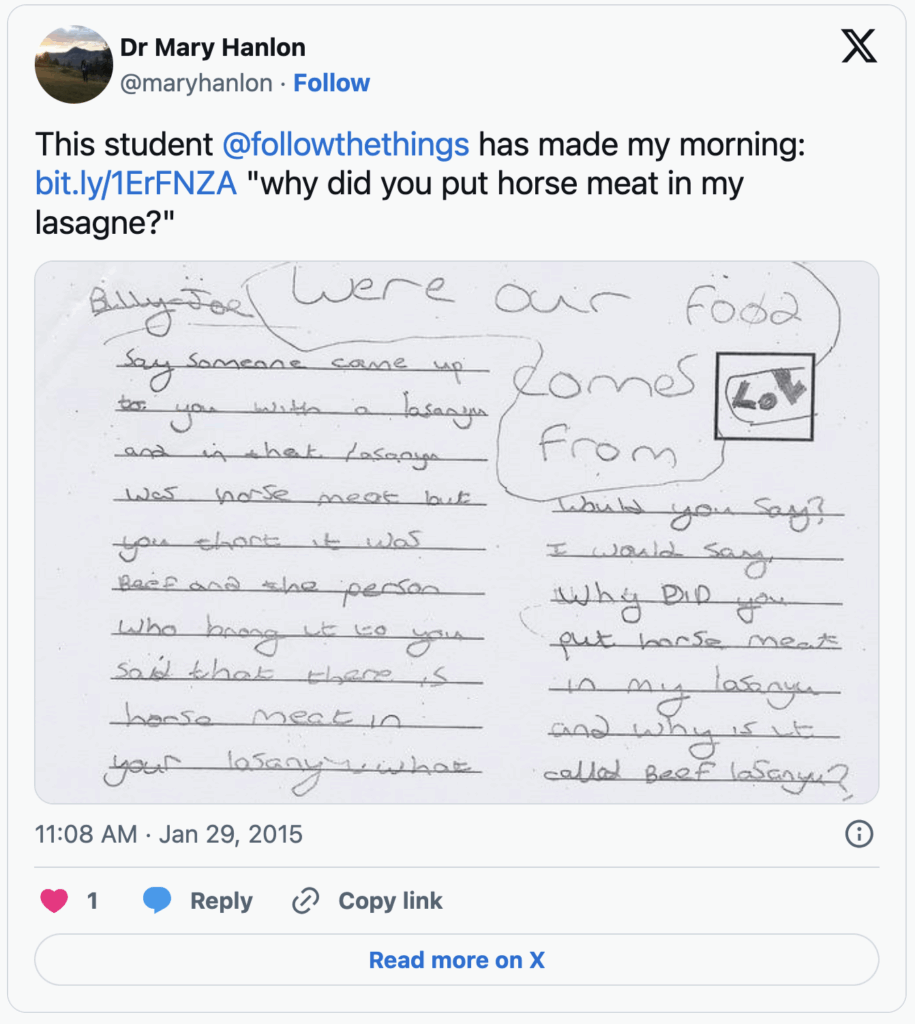

ii) a Sainsbury’s beef pie

Here’s the second, where the children were expressing their concerns about horse meat being found in beef products, and their thanks to those supermarkets where it wasn’t.

e.g. Say someone came up to you with a lasanya and in that lasanya was horse meat but you thort it was beef and the person who brong it to you said that there is horse meat in your lasanya what would you say? I would say why did you put horse meat in my lasanya and why is it called beef lasanya?

c) Beef gelatin in sweets

Here’s the third where, after hearing about the foods in which non-meat cow parts are ingredients, the children expressed their concerns and appreciation about beef gelatin in their favorite sweets. For example:

e.g. Dear Sainsbury’s thanks you for puting meat in swets but I’m Polish and I want mor meat in sweets please plees plees plees … plees plees plees plees plees sainsbury from Alex plees plees plees plees

Feedback

After this story was first published on the followthethings.com blog, the school posted on its website:

Wow, what a successful project! Thanks to Professor Ian for coming in and showing us some of the amazing things we can find if we follow our food back down the production line! The children were amazed to find out about child slavery and their favourite milk chocolate buttons, horse meat and frozen pies and the falling price of milk. This was a great stimulus to produce some really lovely writing. It was amazing to see how caring and sympathetic year 3/4 are! From these pieces of writing, Professor Ian has taken a selection of the most thoughtful cards and put them up on his blog. This is absolutely amazing news for Montgomery as this is the 1st time ever a primary school has contributed to this worldwide website!

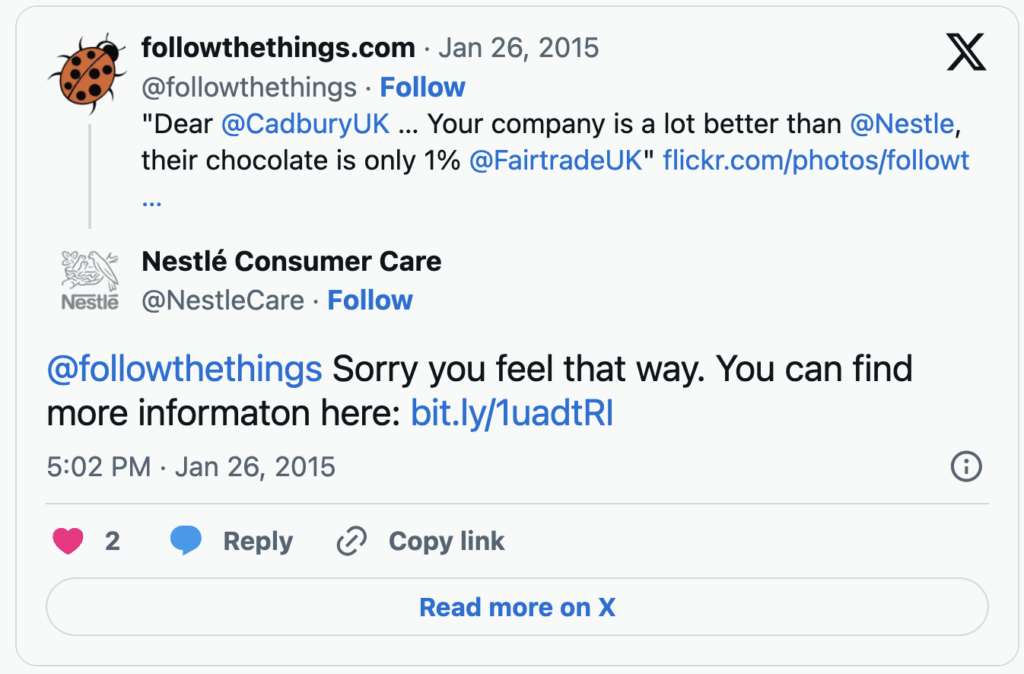

We also tweeted about this work via @followthethings. These were our favorite replies:

Finally

From Joe: This exercise was such a success that Ian was asked by one child if there was more opportunity to be a food researcher! I see a junior followthethinger in the making! All in all it was a thoroughly successful day that I would love to repeat it again!

This post, including its student postcards, was originally published on the followthethings.com blog here.

This page was last edited in September 2025.

Sources

Barlow, A. (2012) Tools of the trade. Primary Geography Autumn, p.22-3

Image credits

Eden Project: followthethings.com

Montgomery School: photos and postcard scans used with permission. Slides followthethings.com

![]()