It’s amazing what you can find out when you’re sitting at a computer, surfing – doing ‘detective work’, using corporate, NGO and news websites, blogs, photo and video-sharing websites and online encyclopaedias. So much information! Where to start? How to narrow it down? Start with the evidence – yes, keywords, right, on those things. Look closely: ‘Made in …’ or ‘Assembled in …’, company names, brands, lists of ingredients – printed on these things, their labels, their packaging – somewhere. OK, open browser: ‘www.google.com’. Search: ‘Marks & Spencer’ and ‘socks’. There are 49,500 hits including a manufacturer’s website, Delta Galil …; a BBC news story: ‘King of socks leaves the UK’ …; a PR Newswire story: ‘Delta Galil addresses discount request from Marks and Spencer’ …; interesting: ‘Jews for Justice in Palestine’ …. What would they have to say about my socks? An article in Red Pepper …: what’s that saying? That fairtrade cotton in M&S’s new sock range is great for farmers in India, but not for anyone else involved in their production, distribution or sale. Right: agriculture, economic restructuring, international politics, boycotts, shifting production, trade justice. In my M&S socks, with my feet, comforting them, protecting them: what geographies are these? My sock geographies…

Source: Ian Cook, James Evans, Helen Griffiths, Lucy Mayblin, Becky Payne & David Roberts (2007, 81-2: on followthethings.com here).

Resources for researchers

On this page, we share some guidance on how you can become a commodity detective in order to find out who makes your stuff.

CEO Ian began to follow things after a frustrating couple of years attempting to teach students about the ‘Lands and peoples of the non-Western world’ in the late 1980s (see FAQs). If only there was some work that could connect their lives to those of the ‘lands and peoples’ we were studying! In the early 2000s, his students were doing this work for themselves, following some simple desk-based research guidelines. Some of their work – following socks, mirrors, medicine, money and more – is published here on followthethings.com.

CEO Ian has refined these ‘follow it yourself’ guidelines though 25 years teaching the ‘Geographies of material culture’ module at the Universities of Birmingham and Exeter in the UK (from 2000-2025: see Angus et al 2000, Cook et al 2007) and through developing education resources with the Fashion Revolution movement, including its online ‘Who made my clothes?’ course (from 2017-2018: see Cook, Jones & Cox 2017-2018). He and his students have published some of this detective work in academic journals, teacher-facing journals, and on the followthethings.com ‘back office’ blog.

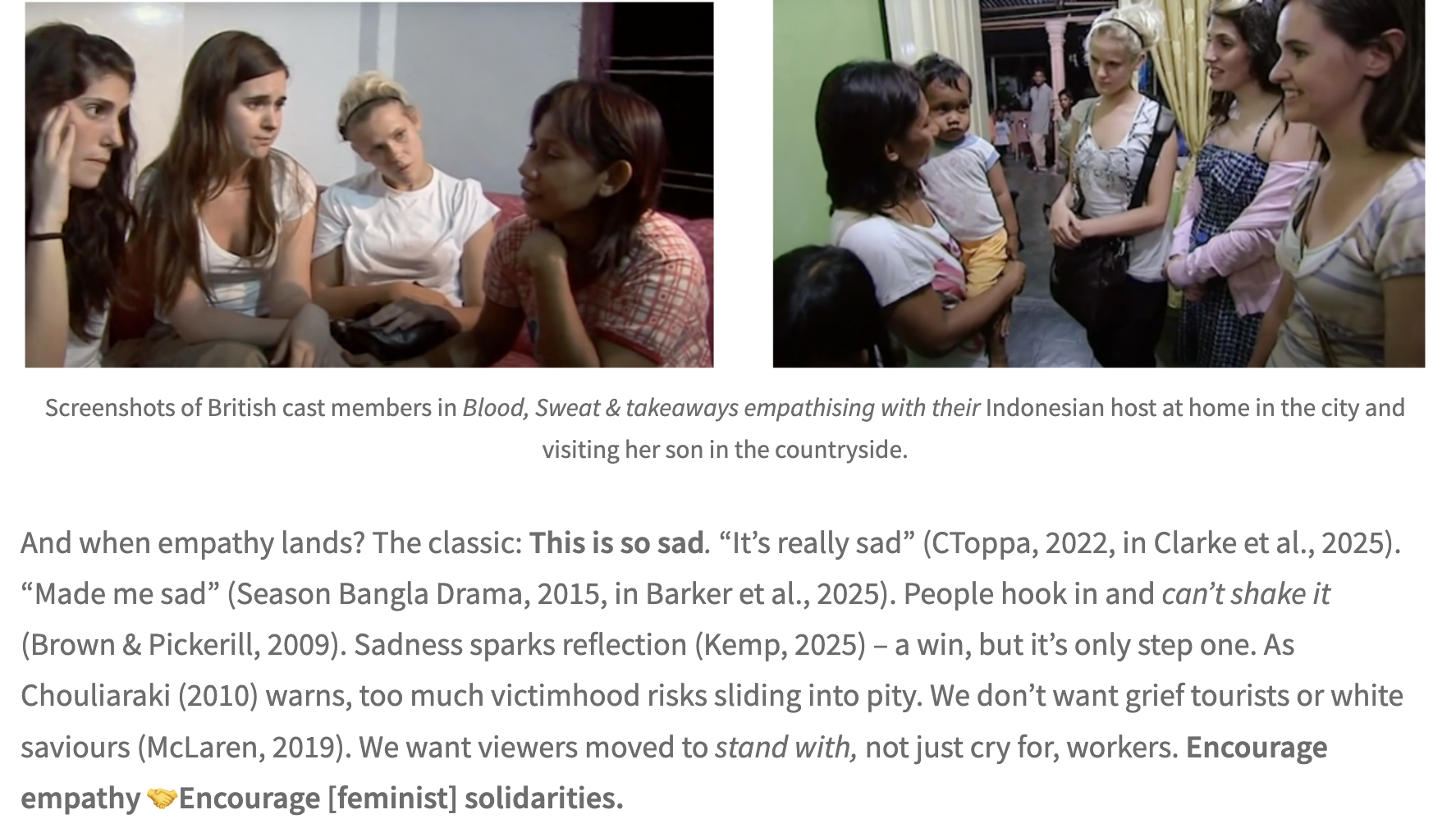

This approach is based on the conviction that when students find out who makes things that matter to them, this learning becomes more meaningful and memorable to them, and can lead to conversations about responsible and ethical consumption. But it’s important to do this work with a sensitivity a) to income inequalities among a group of students in a classroom which can uncomfortably be exposed, b) to the diversity of students’ personal connections the people and places mentioned on ‘made in’ labels because detective work can generate stereotypical – often ‘white saviour’ – narratives involving ‘us’ (consumers) and ‘them’ (producers) (see Siddiqi 2009; Tosin-Talabi 2021), and c) to making students feel solely responsible for any trade injustices they find in their things, when so many other supply chain actors – e.g. corporations to governments to labour unions – are equally, if not more, responsible for them.

[C]alls on solidarity in the global North invite the ‘reader / consumer / activist’ to ‘feel smugly superior’ (Siddiqi 2009, 158) by virtue of their position on the global fashion supply chain, somewhat undoing the solidarity initially invoked. This script offers an appeal to consumers about a way to make shopping matter and falls prey to the neoliberal tendency to address complex structural injustice with individual personal action … [It] essentializes garment workers

into passive victims … while highlighting the ‘conscience’ of the consumer (Horton & Street 2021 p.891 talking about Fashion Revolution’s ‘Who made my clothes?’ campaign).

Below we provide a) the two best inspirations we have found for ‘following it yourself’ to act as a spark for this work, b) two ‘follow it yourself’ detective work guides that we developed for our ‘Geographies of material culture’ courses and ‘Who made my clothes?’ courses, and c) two ways that you can use followthethings.com as a source of case studies and qualitative data for essays and dissertations.

a) inspirations

b) how to ‘follow it yourself’

Who made my stuff?

2025 x Universities of Birmingham & Exeter

Written by Ian Cook et al.

Commodity Detective ‘how to?’ advice | No subject specialism

Who made my clothes?

2017-8 x Fashion Revolution / University of Exeter

Written by Ian Cook, Verity Jones & Kellie Cox

Fashion Detective ‘how to?’ advice | No subject specialism

c) essays & dissertations

Dissertation ideas

2025

Written by Ian Cook et al.

How to use followthethings.com as a inspiration and source of secondary data for a trade justice dissertation | No subject specialism

Sources

Tim Angus, James Evans, Ian Cook et al (2001) A manifesto for cyborg pedagogy? International research in geographical & environmental education 10(2), p.195-201

Ian Cook, James Evans, Helen Griffiths, Lucy Mayblin, Rebecca Payne & David Roberts (2007a) ‘Made in…?’ appreciating the everyday geographies of connected lives. Teaching geography Summer, p.80-3

Ian Cook, Verity Jones & Kellie Cox (2017-2018) Who made my clothes? Fashion Revolution online course (https://web.archive.org/web/20180302164323/https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/who-made-my-clothes [archived 2 March 2018] last accessed 18 August 2025)

Kathleen Horton & Paige Street (2021) This hashtag is just my style: popular feminism & digital fashion activism. Continuum: journal of media & cultural studies 35(6), p.883–896

+2 sources

Dina Siddiqi (2009) Do Bangladeshi Factory Workers Need Saving? Sisterhood In The Post-Sweatshop Era. Feminist review 91(91), p.154–174

Dani Tosin-Talabi (2021) Defeated. (https://followtheblog.org/2021/07/13/decolonising-follow-the-things-teaching-and-learning-defeated/ last accessed 6 September 2025)

Image credit

Header: man putting on a compression sock sitting on the bed (https://stock.adobe.com/uk/images/man-putting-on-a-compression-sock-sitting-on-the-bed/572668068?prev_url=detail) by into (Adobe Stock)

Jeans: University of Exeter

![]()