followthethings.com

Gifts & Seasonal

“Diamonds From Sierra Leone“

A music video starring Kanye West & Jay-Z, directed by Hype Williams, music by Kanye West, Jon Brion & Devo Springstein, for Roc-A-Fella Records.

Original video and remix audio embedded above.

Kanye West is writing and recording a new song commemorating the rebirth of his label Roc-A-Fella Records, including conflicts within the organisation whose hand-signal is the shape of a diamond. Q-Tip, a former member of A Tribe Called Quest, then alerts him to the ‘blood diamond’ scandal in Sierra Leone. So West changes the title of the track to ‘Diamonds from Sierra Leone’ and makes a powerful black and white music video about the supply chain linking the country’s child diamond miners to wealthy white diamond consumers shopping in high end jewellery stores in the USA. One scene parodies a 1990s De Beers’ engagement ring advert, except for the blood that drips from the engagament ring once it’s slipped onto a woman’s finger. In another, a black child’s hand appears from beneath the counter in a jewellery store and hands a diamond to the dealer to hand to a shopper. Later, West leaps from a convertable James Bond-type just before it crashes through the jewellery store window. The video ends with an on-screen plea: ‘please buy conflict free diamonds’. Some audience members point out how a diamond-encrusted mask that West wears on stage, and the bling culture he brags about, makes this plea a bit hypocritical. Others point out a disconnect between the message in the lyrics (about internal record label conflicts) and in the video (about international supply chains and trade injustice). Some core fans aren’t impressed by the track’s sampling Shirley Bassey’s ‘Diamonds Are Forever’ (or harpsichords). So, although West returns to recording more conventional tracks – like his 2005 Crack Music – that his fans want to hear, audience members do start to question the origins of their diamonds (especially after West issues a remix whose lyrics are more directly about the the topic). The video becomes a global smash which – along with Leonardo Di Caprio’s (2006) film Blood Diamond – makes this exploitative trade so public that the industry has to respond. Is this an example of celebrity-fronted trade justice activism that has succeeded, despite – or maybe because of – its flaws? Is this another Global North charity-style representation of abject, improverished life in the Global South that’s caused by guilty, and only solvable through responsible, Western consumerism? Or do its scenes of the child miners and West working together to disrupt diamond supply chains show the kind of ‘global racial solidarities’ that could be mobilised to address this trade injustice? See what you think by reading the comments below.

Page reference: Hector Neil-Mee, Hannah Willard, James Kemp, Harvey Dunshire, Maddy Morgan & Luke Jarvis (2026) Diamonds From Sierra Leone. followthethings.com/diamonds-from-sierra-leone.shtml (last accessed <insert date here>)

Estimated reading time: 86 minutes.

161 comments

Descriptions

While your diamond engagement ring or stud earrings might look gorgeous, they might have a not-so-sparkly background (Source: Lovelyish 2010, np link).

The head-spinning track is built on a stuttery sample of Shirley Bassey’s Diamonds Are Forever (Source: Daly 2005, np link)

Directed by famed hip-hop video artist Hype Williams, the music video …, shot entirely in black and white, opens … (Source: Mukherjee 2012, p.120).

… [by taking] viewers into dimly lit diamond mines, where children are forced to mine for ‘small bits of carbon that have no intrinsic value in themselves, and no value whatsoever to the average Sierra Leonean beyond their attraction to foreigners’ (Source: Brown 2005, np link)

+20 comments

In the thirty seconds or so before the sound of Bassey’s sample becomes recognisable, we hear African voices describing the horrific realities of diamonds as part of the civil war. Once the vocals of Bassey’s ‘Diamonds Are Forever’ are established, the scene moves to early morning in Prague. The setting encodes a sense of ‘class’ and European sophistication and the choice of shooting in black and white works to generate a perceived authenticity … Kanye West is walking along the Charles Bridge, an American in Europe. It makes no narrative sense for him to be doing this other than to establish both his international reach and to perhaps add a sense of European ‘style’ to both himself and to underpin the international scope of the smuggling rings that he discusses. The child miners in the opening shots begin to appear in Prague gravitating towards West as the video’s protagonist (Source: Gardner & Jennings 2020, p.155).

Moving slowly up roughly laid skip rails, the camera catches sweaty children bent over, digging in the heat of serpentine drifts underground. Staring bleakly into the camera, the children wear faces of lost innocence as an armed overseer barks orders at them. Primitive pickaxes, lamps, and a fraying lithograph of a gas-masked rescuer who arrives too late to save a fallen miner suggest crude and perilous working conditions. A male voice-over intones in an African accent: ‘We work in the diamond rivers from sunrise to sunset. Under the watchful eyes of soldiers, everyday we fear for our lives. Some of us were enslaved by rebels and forced to kill our own families for diamonds. We are the children of the blood diamonds.’ Recirculating familiar signifiers of African suffering-emaciated children ravaged by circumstance, hapless victims of cruelty and injustice, ‘Diamonds’ begins by regurgitating clichéd tropes of faraway horrors, muddled tragedies that blight distant lands, contrasting ‘their’ agony against ‘our’ fortunes. Reminiscent of infomercials for charities, popular during the 1980s and 1990s, that featured Western celebrity spokespersons surrounded by abject brown or black children urging viewers to ‘sponsor a child for as little as thirty cents a day,’ ‘Diamonds’ replays familiar cadences of African misery and American magnanimity, isolating the global South as unyielding scene of human tragedy. Unlike the ‘sponsor-a-child’ infomercials, however, ‘Diamonds’ opens with the caption ‘Little is known of Sierra Leone / And how it connects to the diamonds we own.’ Thus, from its start, the video implicates Western demand for African gems within circumstances of hyperexploitation that mark the global trade in diamonds. Refusing its audience the comfort of Western innocence, ‘Diamonds’ suggests instead that the fetishized market in diamonds in the US may be a crucial factor enabling the brutalization of African children (Source: Mukherjee 2012, p.120-1).

A European man proposes to a European woman. He puts a diamond ring on her finger. For a split second, she is delighted but then the ring starts oozing blood all over her hand (Source: Law 2020, np link).

[She] convulses in horror … after … accept[ing] the jewel and the proposal it symbolizes (Source: Mukherjee 2012, p.121).

The camera blurs and refocuses on a child who we can clearly tell have worked in the mines, and who appears to be standing in their hotel room. It’s almost as if the child who may or may not have died, is haunting them … (Source: Law 2020, np link).

… with dilated pupils from retrieving all those diamonds 24/7 (Source: Podersa241 2012, np link).

Puncturing the magical aura of the diamond engagement ring – which, as De Beers has constructed it, best serves its symbolic function when a man spends the equivalent of three monthly paychecks on on it – the scene casts a Macbethian curse on consumptive tokens of romantic love and commitment. The marriage proposal and the engagement ring that vouches for its sincerity, entrenched rituals of heteronormative culture, are thus confronted by the bloody price they exact from faraway workers (Source: Mukherjee 2012, p.121).

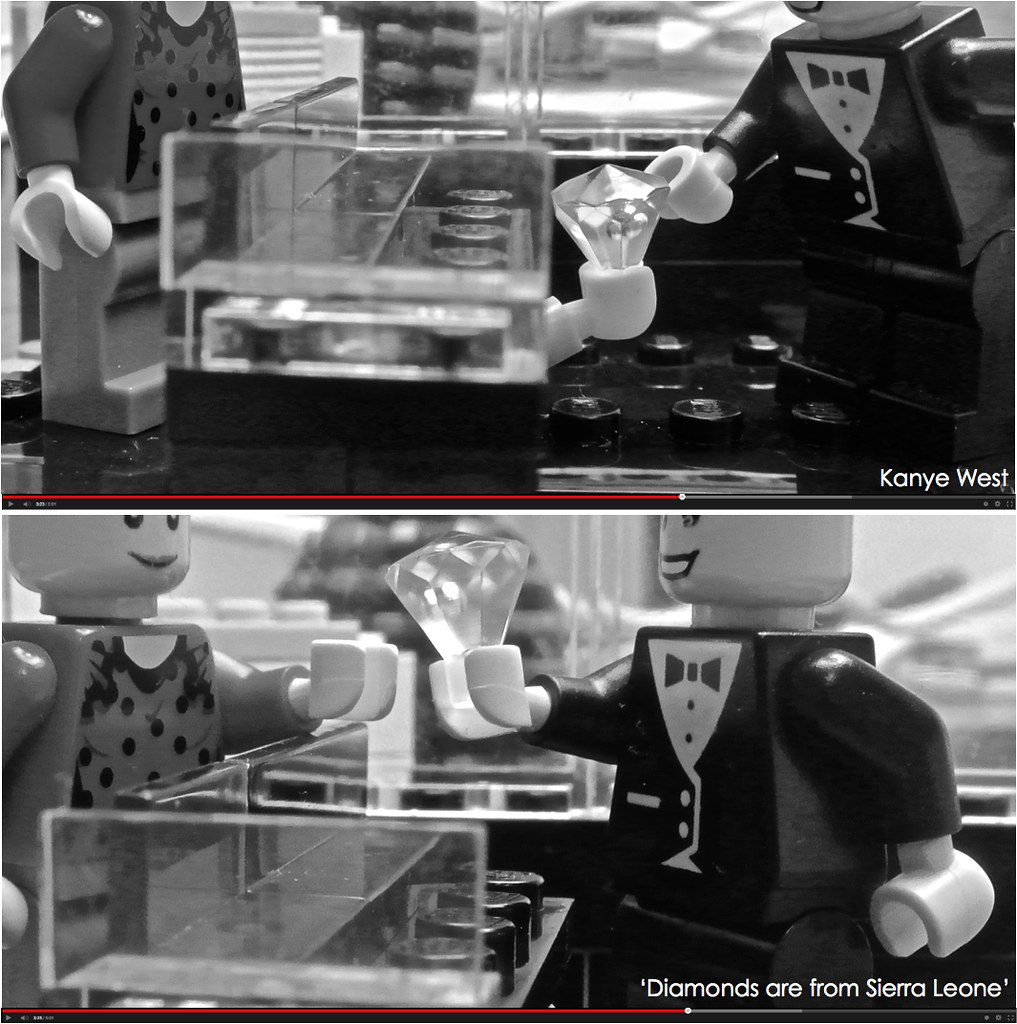

Likewise, scenes of patrician privilege that feature white patrons at an upscale diamond boutique are disrupted as the largest, and presumably most expensive, of the store’s gems is held out for perusal by the skinny dark arm of an unseen African child. As one of the attending suit-clad salesmen leans in to take the jewel from the child’s fingers, he wears a look of caution and embarrassment, anxious about the revelation that the child’s presence threatens. A range of crimes are implicated throughout: certainly, the barbarous rampages of African rebels and impotence of African state authorities but, equally, the greedy collusions of Western traders and willed innocence of Western consumers. ‘Diamonds’ thus, repeatedly and jarringly inserts hyperexploited African workers within rituals and spaces of privileged Western consumerism. Connecting conspicuous consumption in the global North with exploitative relations of production in the global South, the video centrally disturbs the willed innocence of northern privilege as well as the mythic naturalization of southern poverty. West’s audience who, one assumes, knows little of Sierra Leone, is thus forced to consider its role, both active and enabling, within vile secrets of circuits of global trade and neocolonialism (Source: Mukherjee 2012, p.122).

[Lyrically, as the track unfolds] West fully indulges his schizoid nature, rapping about his love of diamonds, the horrific cruelties inside African diamond mines and the current reign of Roc-A-Fella Records, to which he’s signed (Source: Daly 2005, np link)

[He] voices his own inner conflict with diamonds: See, a part of me say keep shinin’ / How? When I know what a ‘Blood Diamond’ is (Source: Brown 2005, np link)

At one point in the video, as West calls out his allegiance to his Roc-a-Fella brotherhood by gesturing the hand sign of ‘The Roc’, a child worker follows, half a world away, moving her hands from her panning basket in shoulder deep waters to form the Roc-a-fella logo with her fingers. … The child rejects one diamond for another, casting off her subjagation for the promise of solidarity (Source: Mukherjee 2012, p.123).

In several scenes, we see West and the African children working together to disrupt the civility and decorum of consumptive rituals in the West. In the final rescue sequence, for example, as West drives a vintage Gullwing Mercedes … (Source: Mukherjee 2012, p.123).

… James Bond style … (Source: Gardner & Jennings 2020, p.155).

… through the window of a diamond boutique, disrupting an ongoing transaction inside, the children help his efforts along, directing him from the backseat and helping him up to his feet after the impact of the crash. As West and the freed children scramble away from the scene, the familial bond they enact underscores the promissory power of global racial solidarities as alliances of mutual advantage (Source: Mukherjee 2012, p.123).

The video ends with West in a church surrounded by the child miners illustrating … a space within the narrative of this video where religion is held up for scrutiny in the face of suffering … (Source: Gardner & Jennings 2020, p.155).

… creating a narrative of resistance and liberation for the child labourers. A second image of West as performer concludes the song at the harpsichord, suggesting that he remains caught up in the performance world (Source: Burns et al 2016, p.163).

Finally, as the video ends, it closes with the caption ‘please buy conflict-free diamonds’. Urging individualized action as a redemptive response to global suffering (Source: Mukherjee 2012, p.126).

[West is] telling people not to buy these conflict diamonds, and instead buy the diamonds which don’t cause slavery and abuse for the people mining them (Source: Stanley 2014, np link).

The video … does shine light on the coldness of the diamond trade and how many children in Africa were murdered or got limbs cut off as a result, many people lost blood because of the diamonds (Source: Nikki nd, np link)

Inspiration / Technique / Process / Methodology

Just as the power of the entertainment industry was harnessed to create a desire, it has now been turned around to spotlight the high cost of that desire (Source: Santora 2006, p.60).

Engagement rings, even in the West, have not always featured diamonds. This ‘tradition’, and the association of diamonds with eternal love and romance, was invented in the advertising campaigns of the diamond cartel De Beers. In 1947, the famous tagline ‘A Diamond Is Forever’ (ranked top advertising slogan of the twentieth century by Ad Age in 1999) was created for De Beers. It became De Beers’ official motto in 1948 and has since accompanied all De Beers engagement ring advertising. Through this slogan, and massive advertising campaigns built upon it – notably involving radio, television and print media reports about royalty and other celebrities sporting diamond jewellery – De Beers created a popular cultural myth on the basis of which it successfully revitalised US diamond sales, which had been falling dramatically since the Great Depression … De Beers later effectively deployed this ‘market driving’ strategy, in which a company seeks ‘to reshape, educate and lead the consumer, or more generally, the market’ … – or, in other words, engages in economic propaganda – to transplant these Western-invented matrimonial representations and practices to Japan in the 1970s … and to China in the 1990s and beyond, where diamonds are perceived as white and thus unlucky … The diamond engagement ring, and its seemingly obvious popular cultural ‘meaning’, is the product of the global marketing practices of a major commercial cartel and an instance of cultural globalisation (Source: Weldes & Rowley 2015, np link).

Diamonds are Forever, [is a] 1971 film, part of the globally successful Cold War 007 franchise, in which British spy James Bond simultaneously combats South African diamond smuggling and an interconnected global nuclear threat. The film’s title song, sung by Shirley Bassey, together with ‘Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend’ (from Gentlemen Prefer Blondes [1953], famously performed by Marilyn Monroe and also included in Moulin Rouge [2001]), and Madonna’s ‘Material Girl’, all construct – in complex ways – the diamond, and diamond jewellery, as integral to women’s identities and relationships with men. On the one hand they represent the diamond ring as a quintessential symbol of (heterosexual) romantic love and eternal attachment. On the other, however, women gain financial security from their expensive jewellery and sometimes have a more reliable relationship with the trustworthy jewel(lery) … . In some contexts (and contra the ‘eternal love’ trope), the diamond engagement ring offered, or was thought to offer, a financial surety for women who had consented to sex before marriage with their fiancés and were subsequently jilted … Finally, the diamond (and jewellery more generally) regularly appears in state diplomacy, perhaps most notably in the UK. The famous Indian Koh-i-Noor diamond, presented to Queen Victoria in 1850 (as a spoil of war), was set into the British Crown Jewels in 1937 … This diamond (and others in the Crown’s possession) remains contentious symbols of British colonialism and exploitation. India recently demanded, again, that it be returned; UK Prime Minister David Cameron again refused … Queen Elizabeth II is regularly gifted with diamonds and other precious stones and jewellery, some of which, when the Queen functions as ‘the personification and symbol of Britain to the outside world’ …, are deliberately redeployed as/in public diplomacy. When the Queen visits New Zealand, for example, she wears the diamond fern brooch given to her by ‘the women of Auckland’ on her first tour of New Zealand in 1953 … ; it was similarly worn, more recently, by the Duchess of Cambridge … While these particular diamonds do not represent romance, they do represent state identities and the undying allegiance of the New Zealand ‘people’ to the British Commonwealth and monarchy (Source: Weldes & Rowley 2015, np link).

+42 comments

Late in the summer of 2005, hip-hop superstar Kanye West released his highly anticipated second album, Late Registration. Among the songs on the album, West unveiled the music video for the single ‘Diamonds (Are from Sierra Leone)’ that offers a stylized indictment of human rights atrocities fuelled by the global trade in African ‘blood diamonds’. … [It] opens with the caption ‘Little is known of Sierra Leone / And how it connects to the diamonds we own’ (Source: Mukherjee 2012, p.113).

Raising thorny issues about child soldiers, slave labour, and the culpability of the global diamond industry within these conditions, West’s video appeared in the midst of a surge of Western interest in the ‘conflict diamond’ trade and its humanitarian costs. … Sold illegally to finance insurgencies, war efforts, and warlord activities, the trade in blood diamonds drew international attention when reports emerged that these armies routinely and forcibly conscripted African children as slave labourers. … The World Diamond Council … estimated that at the height of the atrocities in the late 1990s, conflict diamonds represented approximately 4 percent of the world’s diamond production (Source Mukherjee 2012, p.114-5).

Kanye West’s ‘Diamonds (Are from Sierra Leone)’ emerged within this context together with singles by other high-profile hip-hop stars like Talib Kweli (‘Going Hard’, 2005), Nas (‘Shine on ‘em’, 2006), Lupe Fiasco (‘Conflict Diamonds’, 2006) and Kubus and BangBang (‘Conflict Diamonds’, 2007) that sought to raise awareness ‘not just about innocent lives being taken in … Sierra Leone, nor … about the way the reins of the diamond industry are help by one particular diamond digger … but that hip-hop is allowing itself literally to be pimped out to further the continuation of such atrocities’ (Source: Mukherjee 2012, p.116-7).

West’s decision to take a public stand on issues raised by the global trade in diamonds is not uncharacteristic of the artist’s emerging oeuvre. Recognized by music critics as operating ‘far outside rap’s usual strictures… the only mainstream rapper willing to tackle politics’ and ‘a brilliant social commentator unafraid to tackle [sensitive] subjects.’ West’s music has lamented the blunting of black political militancy by drug use (‘Crack Music,’ 2005), the impact of class inequities on US health care (‘Roses,’ 2005), and the scourge of AIDS, which West claims he ‘knows the government administered’ within black communities (‘Heard ‘Em Say,’ 2005). In perhaps the most widely viewed of his public outbursts, West’s political voice found an attentive audience when the artist stepped off script during an appearance on ‘A Concert for Hurricane Relief,’ NBC’s nationally televised benefit for victims of [Hurricane] Katrina in September 2005, to denounce the president’s appallingly feeble relief efforts, saying, ‘George Bush doesn’t care about black people’ (Source: Mukherjee 2012, p.119).

West originally wrote Diamonds … to commemorate the rebirth of the Roc-a-Fella dynasty (Source: Anon nda, np link).

[It] prominently samples the Shirley Bassey theme ‘Diamonds Are Forever’ created in 1971 for the James Bond movie of the same name (Source: Mukherjee 2012, p.122).

The best thing about writing a James Bond theme song is that the whole world hears it. It’s very hard these days to get a song to last, and to create any kind of standard, so I’ve been very lucky to have Diamonds Are Forever … It was a great surprise when Kanye West sampled it, too … That’s another reason people know it now. It was fantastic (Source: Black in Garner 2019, p.47).

[Kanye] West[‘s] version reframes the song to consider issues of materialism and oppression that are latent in Bassey’s performance (Source: Gardner & Jennings 2020, p.140)

Bassey’s iconic connection with the song … imbued the musical text with a richness of meaning that Kanye West then creatively used to ‘restory it’ (Source: Gardner & Jennings 2020, p.157).

West’s track is, from the start, global. The song makes use of Wales native Dame Shirley Bassey’s ‘Diamonds Are Forever,’ the theme song for the homonymous Bond movie, with verses [in the remix] from the Brooklyn born Jay-Z and the Chicagoan West, while the original video was shot in Prague and directed by African-American and Honduran Hype Williams in order to tell the story of conflict diamonds and violence in Sierra Leone (Source: Beswick & Johnson 2021, p.10).

To sample [Bassey] a Black British singer, to use her song from a 1971 Bond film, is to extend the genealogical reach of hip-hop across borders, of time and nation. West broadens on the hip-hop family to include the Welsh singer from Tiger Bay, an historically disadvantaged area in the Welsh capital city Cardiff, now gentrified and rebuilt. As indicated earlier, place matters to how Bassey has been positioned within British media representation and in the generation of her star persona; she has always been ‘the girl from Tiger Bay’ but when West cites her, this provenance is not as important as the contemporary resonance (the successful glamourous diva and Dame [of the British Empire]) and relevance of the sound, and the phrasing of her voice. … In her performance of the song, her identity as a Black Welsh woman is important when we start to consider Kanye West’s treatments of it. This is because the song and its sampling, the 1971 Bond film and the 2005 music video that accompanied the West track, can be considered as related events in what might be described as an ‘unexpected encounter’ …, a trait that arguably characterises hip-hop aesthetics (Source: Gardner & Jennings 2020, p.147-8).

When reworking Bassey’s version of ‘Diamonds Are Forever’, a political awareness of colonial injustice is brought to Kanye West’s new mix. It is of course open to speculation as to whether he is knowingly or unknowingly engaging with the racist legacies of the [James Bond] novel and the film, when he reversions it (Source: Gardner & Jennings 2020, p.148).

Bassey … threatened to sue over the use of her song, explaining, ‘He didn’t ask my permission to have me singing on the his song. I didn’t even know it existed until I heard him performing at the Live 8 concert [in 2005]. I didn’t even hear from his record company, which wasn’t very nice’ (Source: Hartmann 2012, np link).

[In Bassey’s song] diamonds are better than men or love because they can be counted on to ‘never lie,’ to ‘never leave in the night.’ Thus, in its first writing, ‘Diamonds’ began as a call to brotherhood among Roc-a-fella artists, suggesting that, like diamonds, Roc-a-fella is ‘for-ever,’ a family that will never lie, never leave you in the night (Source: Mukherjee 2012, p.122).

The brutal civil war in Sierra Leone lasted from 1991-2002, and in the post-Cold War political context in which it took place, was generally perceived as somewhat detached and distant from Europe and America. As Prestholdt explains: ‘the raw reality [was] that much of the world saw its destruction as inconsequential’ (2009, 202). In the war, diamonds were, it is claimed, used to trade arms and fuel Charles Taylor’s RUF (Revolutionary United Front) which was operating in Sierra Leone and in Liberia … The purchase of these diamonds therefore financially supported brutal guerrilla forces that used child miners to supply diamonds to the arms traffickers and who, at the same time, also used child soldiers to implement brutality and terror (Source: Gardner & Jennings 2020, p.151).

For eleven years, gangs of RUF child soldiers hacked off the arms of their enemies and even bystanders, either at the elbow – ‘short sleeves’ – or wrist -‘long sleeves.’ Just as the conflict was ending in the early 2000s, such atrocities – and the diamonds that gunmen traded to buy arms – came into the global spotlight. … [This is when] Kanye West released … ‘Diamonds From Sierra Leone’. More than 50,000 died in tiny Sierra Leone and another 250,000 in Taylor’s Liberia (Source: Hinshaw 2012, np).

Kanye West … said [when] he wrote this song, he just called it Diamonds and it was basically based on Roc-A-Fella and the break up of them (Source: katexx 2010, np link).

The chorus, ‘Throw your diamonds in the sky’ refers to the Roc-A-fella hand signal, which is the shape of a diamond (Source: Anon ndb, link).

But Mark Romanek and Q-Tip (directors) .. said it reminded them of the kids getting killed in Africa (Source: katexx 2010, np link).

[A]fter [West] heard [this] … he said that he saw a different meaning in the song (Source: Anon nda, np link).

In an interview for MTV News, West explains that while he was recording the single, he heard about conflict diamonds and ‘kids getting killed [and] amputated in West Africa.’ The artist explained: ‘Mark Romanek, the director who [designed the video for] Jay [Z]’s 99 Problems, and Q-Tip [lead rapper in the iconic 1990s hip-hop group A Tribe Called Quest] both brought up blood diamonds. They said, “That’s what I think about when I hear diamonds. I think about kids getting killed, getting amputated in West Africa.” And Q-Tip’s like, “Sierra Leone,” and I’m like, “Where?” And I remember him spelling it out for me and me looking on the Internet and finding out more.’ We find a lucid moment of political conscience emerging from hip-hop brotherhoods here, fraternities that work as knowledge networks for activist strategies that, in this case, underscore the urgency of cementing a transcontinental bond of ‘brothers-in-arms’ across the global North and South (Source: Mukherjee 2012, p.123).

Kanye said ‘I think that was just one of those situations where I just set out to entertain, but every now and then God taps me on the shoulder and says, “Yo, I want you to do this right here,” so he’ll place angels in my path and one angel will lead to another angel and it’s like a treasure hunt or something. And I finally found the gold mine, which was the video “Diamonds (From Sierra Leone)”‘ (Source: katexx 2010, np link).

Once you find out about ’em’ and you find out what went on, what’s going on, every time you look at a diamond you’ll think of that. You’ll think about, you know, the massacres, the murders, the amputations. You’ll think about the war once you know about it (Source: West in Son of an Assassin 2022, np link).

[H]e wanted to help promote awareness. He wants people to realize that when you purchase diamonds, you don’t really know where your diamond came from. There is a chance that a small child paid the price so you can look glamorous (Source: Anon nda, np link)

[So, h]aving boned up on the subject, West promptly changed the title and themed the video accordingly but it was too late to alter the lyrics. The result is a curious compromise, a protest song in name only (Source: Crosley 2005, np link).

If you listen to the song Kanye doesn’t really address the [Blood diamonds] issue but he does so in the music and the song title and I think that is a more effective way to do it. The visual [narrative of the video] forces you to see whats going on in Sierra Leone instead of just rapping about it and hoping the audience gets what he is saying (Source: md922 2013, np link).

West made two versions of song, each sampling the theme song from the James Bond film Diamonds Are Forever by Shirley Bassey (Source: Dudding 2011, p.29 link).

[Both] foreground… diamonds as they are articulated and connected to Shirley Bassey’s performance and star persona (Source: Gardner & Jennings 2020, p.151).

The original track showcases West’s anger about being passed over during the 2005 Grammy Awards (Source: Dudding 2011, p.29 link).

[Sample lyrics from the original:]

I was sick about awards, couldn’t nobody cure me

Only playa that got robbed but kept all his jewelry

Alicia Keys tried to talk some sense in him

30 minutes later seein’ there’s no convincin’ him

What more could you ask for? The international asshole

Who complain about what he is owed?

And throw a tantrum like he is three years old

You gotta love it though, somebody still speaks from his soul

And wouldn’t change by the change or the game or the fame

When he came in the game, he made his own lane

Now all I need is y’all to pronounce my name

It’s Kanye, but some of my plaques, they still say ‘Kayne’

Got family in the D, kinfolk from Motown

Back in the Chi, them Folks ain’t from Moe Town

Life movin’ too fast, I need to slow down

Girl ain’t give me no ass, you need to go down

My father been said I need Jesus

So he took me to church and let the water wash over my caesar

The preacher said we need leaders

Right then, my body got still like a paraplegic

You know who you call, you got a message, then leave it

The Roc stand tall and you would never believe it

Take your diamonds and throw ’em up like you bulimic

Yeah, the beat cold, but the flow is anemic

After debris settles and the dust get swept off

Big K pick up where young Hov left off

Right when magazines wrote Kanye West off

I dropped my new shit, it sound like the best of

A&R’s lookin’ like, “Pssh, we messed up”

Grammy night, damn right, we got dressed up

Bottle after bottle ’til we got messed up

In the studio with Really Doe, yeah, he next up

People askin’ me if I’m gon’ give my chain back

That’ll be the same day I give the game back

You know the next question, dog, “Yo, where Dame at?”

This track the Indian dance to bring our reign back

“What’s up with you and Jay, man? Are y’all okay, man?”

They pray for the death of our dynasty like “Amen”

But r-r-r-right here stands a man

With the power to make a diamond with his bare hands

(Source: West 2005, np link).

[A]lthough the lyrics point to a self-reflexive or ‘internal’ modality, the video reveals his understanding of the external forces that drive the cultural phenomena of interest to him (Source: Burns et al 2016, p.164).

In Kanye’s defense he does have a remix to the song where he does talk about the issue Sierra Leone but it wasn’t a single so there was no visual to it (Source: md922 2013, np link).

[In the] Jay-Z-blessed remix … (Source: Rabin 2005, np link).

… West acknowledges that the origins of his jewellery may be far from harmless (Source: Headley 2005, np link).

[This] reiterates one of the recurring themes in West’s music: the tension between criticizing consumerism and feeling powerless to resist its temptations. West is the kind of preacher who has no problem letting everyone know he’s one of the biggest sinners in church, and his self-deprecating, humanizing take on spirituality helps explain why he’s managed to smuggle Jesus onto the hip-hop charts, and ride socially conscious rap to multiple platinum plaques (Source: Rabin 2005, np link).

[Sample lyrics from the remix:]

Good Morning, this ain’t Vietnam still

People lose hands, legs, arms for real

Little was known of Sierra Leone

And how it connect to the diamonds we own

When I speak of Diamonds in this song

I ain’t talkin bout the ones that be glown

I’m talkin bout Rocafella, my home, my chain

These ain’t conflict diamonds,is they Jacob? don’t lie to me mayne

See, a part of me sayin’ keep shinin’,

How? when I know of the blood diamonds

Though it’s thousands of miles away

Sierra Leone connect to what we go through today

Over here, its a drug trade, we die from drugs

Over there, they die from what we buy from drugs

The diamonds, the chains, the bracelets, the charmses

I thought my Jesus Piece was so harmless

’til I seen a picture of a shorty armless

And here’s the conflict

It’s in a black person’s soul to rock that gold

Spend ya whole life tryna get that ice

On a polo rugby it look so nice

How could somethin’ so wrong make me feel so right, right?(Source: West & Jay-Z 2005, np link).

Jay-Z, … hops on toward the end of the track, talking about an entirely different conflict: his ongoing feud with former partner Dame Dash, who, in the June issue of XXL, said that Jay took the Roc-A-Fella name and essentially forced Dame out of the business they built together. ‘The chain remains, the gang is intact / The name is mine, I’ll take blame for that,’ Jay raps. ‘The pressure’s on, but guess who ain’t gon’ crack / Pardon me, I had to laugh at that / How could you falter when you’re the rock of Gibraltar? / I had to get off the boat so I could walk on water’ (Source: Crosley 2005, np link).

On June 15, 2005, the remix of ‘Diamonds from Sierra Leone’ … impacted radio in the US, through Roc-A-Fella and Def Jam. It was later released for digital download in the country on July 5. On August 30, 2005, the remix was included as the thirteenth track on [the album] Late Registration, coming seven places before the original (Source: Wikipedia nd, np link).

‘Diamonds from Sierra Leone’ entered the US Billboard Hot 100 at number 94 for the chart issue dated May 21, 2005. The song reached number 83 in its third week on the Hot 100, before declining 11 places back to number 94 on the issue dated June 11, 2005. The following week, the song rebounded by 36 positions to number 58 on the chart. The song fell down the Hot 100 again by five places to number 63 on the issue dated June 25, 2005, though eventually surpassed the rebound position by peaking at number 43 in its 12th week on the chart. ‘Diamonds from Sierra Leone’ lasted for 19 weeks on the Hot 100. The song further peaked at number 21 on the US Billboard Hot R&B / Hip-Hop Songs chart for the issue date of July 2, 2005. It debuted at number 18 on the US Hot Rap Songs chart issue dated May 14, 2005, ultimately climbing to number 11 three weeks later. The song further peaked at number 24 on the US Rhythmic chart. On November 20, 2018, ‘Diamonds from Sierra Leone’ was certified platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) for pushing 1,000,000 certified units in the US. The track was most successful in the United Kingdom, charting at number eight on the UK Singles Chart, which it spent 16 weeks on. For 2005, the track ranked at number 98 on the year-end chart. On October 4, 2019, the track was certified silver by the British Phonographic Industry (BPI) for sales of 200,000 units in the UK. As of October 24, it stands as West’s 39th most successful track of all time in the country. The track experienced similar performance in Denmark, peaking at number nine on the Tracklisten Top 40. It reached numbers 16 and 17 on the Norwegian VG-lista Singles Top 20 and Finnish Singles Chart, respectively. The track also attained a top 20 position in Ireland, peaking at number 19 on the Irish Singles Chart. It was less successful in Sweden, charting at number 30 on the Sverigetopplistan Singles Top 100 (Source: Wikipedia nd, np link).

West performed the song live on the fourth episode of Wild ‘n Out in 2005, while he performed it at Abbey Road Studios in London on September 21, for his first live album Late Orchestration (2006). … West performed ‘Diamonds from Sierra Leone’ as the opener to his set at the 2006 Coachella Festival, where he wore a T-shirt in tribute to American trumpeter Miles Davis. On July 1, 2007, West performed the song at 8:56 p.m. as the last number of his set for part 3 of Princess Diana memorial event Concert for Diana at Wembley Stadium, London, a week before he delivered a performance of it for the Live Earth concert at Giants Stadium in East Rutherford, New Jersey. West quickly made his way to the stage at the Edinburgh Corn Exchange for T on the Fringe 2007 while the sample of ‘Diamonds Are Forever’ on ‘Diamonds from Sierra Leone’ played, before he performed the song. The performance saw him accompanied by a full-sized harp and a large group of tall violinists that wore golden ball gowns, and was reacted to positively by the crowd. At Summer Jam 2008 on June 1, West started his appearance by performing ‘Diamonds from Sierra Leone’. He was backed by explosive lights, pyrotechnics, and a multiple-piece band, though focused heavily on the music while hunched over. … West provided a performance of the song at the 2011 Coachella Festival. West performed a shortened version of it as part of a medley of over 10 songs for 12-12-12: The Concert for Sandy Relief at Madison Square Garden in New York City on December 12, 2012, while rocking a Pyrex hoodie and leather kilt. He performed the song for his headlining appearance at the 2014 Bonnaroo Music Festival. The tempo for West’s headlining set at the 2015 Glastonbury Festival went up from earlier during his performance of the song, which began from the set’s 1:05:37 mark. The crowd cheered loudly in response to the performance, as well as yelling the lyrics back at West (Source: Wikipedia nd, np link).

[C]ultural interventions of the sort that ‘Diamonds’ epitomizes reveal the muddled force and consequence of ‘commodity activism’ as it attempts to reappropriate neoliberal consumerism and entrepreneurialism to activist ends. The video offers several moments of provocation exemplifying these contradictions. For one, West’s attack on the diamond industry may be surprising given that the star is an icon within the giddy spectacles of bling culture. If, like others within the world of hip-hop, West’s engagement with the brand aesthetics of bling appears to contradict his political stand against blood diamonds, it may be significant that the star learned about the horrors of the trade within the cultural milieu of bling, a milieu often written off as narcissistic and pathological. Thus, ‘Diamonds’ offers a keen example of cultural resistance-replete with contradiction and paradox-that emerges from within neoliberal hegemonies of entrepreneurial individualism and materialist pleasure. Likewise, the final rescue in ‘Diamonds’ is orchestrated by converting a vintage luxury automobile, an iconic symbol of status within the emulative cultures of conspicuous consumption, into a weapon of militant disruption, ramming it headfirst into the genteel civility of the diamond boutique. Striking one mode of consumerism using totems of another, the scene is laden with contradiction: the anticapitalist protest that finds its resistive voice through iconic consumerism (Source: Mukherjee 2012, p.124-5).

The message of ‘Diamonds from Sierra Leone (Remix)’ seeks not only to entertain or even inform, but also to inspire critical self-reflection and practical action on a significant contemporary issue. In creating this song and delivering his message, West unites his aesthetic production with pragmatic reflection and application by his audience (Source: Boeck 2014, p.219).

Discussion / Responses

I just saw this new Kanye West video about ‘blood diamonds’ in Sierra Leone, and I’m afraid that my diamond might have funded torture or slavery, and I think maybe I’m a bad person for having it (Source: Cole 2005, np link)!

The first time I saw this video was in college during one of my comm courses when my favorite professor showed it to our class. The entire time this video was playing, you could tell he was working really hard to not dance along to it. As was I (Source: Howveryheather nd, np link).

this is a really good song but the part that goes ‘forever ever forever ever?’ and gets really high pitched is annoying. But the fact that it’s a rap song that actually has a meaning beyond criminal activity, self-indulgent lifestyle and promiscuous women makes up for any part of it that might be annoying (Source: Marissa nd, np link).

I had heard that Kanye West was ‘intelligent’ and that he actually rapped about more than sluts and expensive, tacky items; so when I saw that he had a song out titled ‘Diamonds from Sierra Leone’ I was incredibly excited, I have studied conflict diamonds and it’s an issue I feel very strongly about. When I first listened to the song, I didn’t think I heard anything about blood diamonds, second listen produced only the line ‘Take your diamonds and throw ‘em up like you bulimic’. I was pretty irritated, but just to make sure that I hadn’t misheard, I came here [to the Song Meanings website] and saw this [post], which showed even shallower than I originally thought I had heard. Please don’t tell me that I am the only person that is totally appalled by this song – it seems to me he’s trying to cash in on that whole deep and meaningful rapper image without putting the effort into actually writing deep or meaningful lyrics. He can write whatever the hell he wants, but the title is totally misleading and his apparent cashing in on the tragedy associated with the misery and death of countless men, women and children is DEPRESSING. I can’t be the only person that sees the outrageousness of this song and it’s title – since he wrote a pointless, cliche song about sluts, cars, and a regurgitated rags-to-riches story, he should’ve titled it appropriately and left off any mention of Sierra Leone (Source: Bella_x 2006, np link).

+66 comments

[The] intro voice is so haunting. Makes me think of a very rich older lady has been through so make heartbreaks, all she has is her diamonds. No friends (Source: CalideCali 2025, np link).

love when rap is about something. love when rap is social activism. love when rap is educational. It’s the best medium to speak up and so many use it to talk about stupid stuff. Amen to rap songs like this (Source: Manicpixiedream nd, np link).

Beautiful master piece, I believe the synopsis is that a material thing like a diamond has no value compared to a persons life or a childs for that matter (Source: Sanchez 2012, np link)

One of my favorite Kanye songs / videos, it’s so damn powerful and makes you think like cuhrrrazyyy (Source: Rundevil-run nd, np link).

Easily one of my favorite Kanye videos. But that’s because i’m into all that conscious stuff. but can you blame me? even if you can, i don’t care. The concept definitely strikes a chord in my heart. These conflict diamonds are still out there and people will keep buying them for engagement rings, earrings or whatever … i guess diamonds are a girl’s best friend or an African child’s worst nightmare (Source: Illcitydiaries nd, np link).

He speaks of an issues that we, mainly rappers, are addicted to and shows us how our addiction can hurt others. In one song, he discusses problems in society, problems within himself and his group, and problems within ourselves. Women are taught to believe that diamonds are their best friends and that receiving them should guarantee happiness. In reality, that temporary happiness has created permanent suffering for those who had to mine the diamonds (Source: Kann-yeezi nd, np link).

… it’s so creative. By ‘The Rock’ he means Roc-A-Fella records and how they will be on top ‘for ever’. Now listen to the lyrics again thinking about the fact that he’s talking about diamonds – his fame, ‘diamonds are forever’ as in diamonds never change and his record label. Amazing song. Im high (Source: nymphomaniacgorilla 2012, np link).

‘Good Morning! This ain’t Vietnam / Still, people lose hands, legs, arms for real / Little was known of Sierra Leone, and how it connect to the diamonds we own…‘ Kanye West, ‘Diamonds from Sierra Leone’ … These lyrics may be part of a popular song, but they paint an all too realistic picture of the deadly blood diamond trade that persists in West Africa. During Sierra Leone’s decade-long civil war, rebel forces and warlords funded their actions with billion-dollar profits from the diamond trade. But even though the war has ended, this cruel and violent by-product has not (Source: Talbot 2012, np link).

The Diamond Information Center released a statement saying [the remix] lyrics ‘do not reflect the tremendous work the diamond industry has done’ in stamping out conflict diamonds. ‘The issue of conflict diamonds is one that the industry has always taken very seriously,’ says Carson Glover, spokesman for the Diamond Information Center. ‘The volume of conflict diamonds in circulation is believed to have dropped below 1 percent, if any at all, and it is virtually impossible for unscrupulous dealers to sell noncertified rough diamonds’ (Source: Bates 2005, np link).

I’ve been giving speeches and talking about the slave trade on diamonds in Sierra Leone for years. I was really happy to hear about this song. I wish it talked more about the tragedy in Sierra Leone, and less about Vegas or Alicia Keys. But I still really appreciate that he put this out there and let the world at least start to realize what’s going on in Africa. Stop supporting genocide, stop buying diamonds (Source: Elaine 2005, np link)!

peace y’all, I have a friend (totally platonic) that I helped come to this country from Sierra Leone after he, his mom, 2 brthers and 1 sister watched their dad – from the window of an abandoned bus (that they had been trapped on for days) be killed… By Americans in pursuit of that clear rock that GOD allows to grow in abundance in the mountains of their country (Source: iamnina04 2012, np link)

[The scene where a] man proposes to his girlfriend and soon after he puts the the ring on her finger the woman’s hand start to bleed while an African girl is in the background … is so powerful because when we get these items like diamonds we are happy and excited but if we ever know where these items come from and the struggles that these items cause to people we wouldn’t really want to purchase them as much (Source: md922 2013, np link).

It bugs me that it was only white people buying the diamonds, they were purposely meant to look like the bad guys (Source: dennis3dc 2014, np link).

Black people don’t use diamonds? This video it’s so racist (Source: Coelho 2014, np link)!

Yes it is racist – but if you’re white, you’re not allowed to call out racism. You’re supposed to sit down, be silent and meek and let the poor discriminated against minorities shake their fists in contrived outrage at their white oppressors (Source: Jeff 2014, np link).

Anti racist is a codeword for Anti white (Source: Wayne 2014, np link).

he should of had some ignorant gangster rappers wearing all their chains. The problem in africa isn’t coming from white people buying 1 wedding ring. I doubt rick ross or 2chainz is giving a shit if they wear conflict free diamonds or not (Source: North 2014, np link).

Your buggin man the percentage of jewlery sales that rappers account for is so miniscule compared the amount of money whites spend across the West. … but I do agree that these rappers should be criticized for overly glorifying jewlery that destroys millions of ppls lives (Source: Donald 2014, np link).

lol I think he’s saying white people was the worst thing that ever happened to Africa (Source: Aceprocta 2014, np link).

The white people buying the diamonds was a representation of the WESTERN FORCES DEPLETING AFRICAN RESOURCES. … haha at least that’s what i think (Source: MuchLove 2014, np link).

Kanye makes white people look like the villains when it’s these Africans own country that is making them slave for these diamonds (Source: SF49erfan1000 2014, np link)

If white people didn’t come to Africa in the damn first place, people wouldn’t even wear diamonds. Maybe if white people were not so greedy, slavery against black people wouldn’t have happened (Source: Honey MK 2014, np link)

If u listen to the lyrics he isnt talking about a single race gettn caught up n the diamond wearing and flashing them and whatnot …. hes talking bout everyone who caugt up In it and not being aware of how those diamonds we love so much has a sick history … and he does make a few references about blacks and diamonds (Source: Smith 2014, np link).

There is clearly a point here, about the rich (white and black) joyfully showign off their diamonds without sparing a thought for those whose lives are ruined by the trade of them, not to mention the civil wars and oppression in these countries, but it’s suppressed by the desire to make something MTV-friendly, and boast about how everyone was wrong about him, and now he’s got loads of money. The apparent reference to God towards the end is a bit naff as well (Source: Jackofhearts 2005, np link).

hey this is anesu from africa , harare, kanye you are the best keep it up my man . DIAMONDS is good here in africa they all feel you are the only artist who glorifies africa. GOD WILL STAND BY AFRICA, WE ALL KNOW WAT THE [US PRESIDENT] BUSHES AND [UK PRIME MINISTER] BLAIRS HAVE DONE TO US. LET ALONE BLACK HITLERS HAVE RISEN AMONG OUR PEOPLE …… CHEERS (Source: Musora 2005, np link).

A song like that from a guy wearing massive jewelry and furs, that’s quite interesting isn’t it (Source: Romain M 2014, np link)?

When he signed his deal with Roc-A-Fella he went straight to every US rappers’ favourite jeweller, New York’s Jacob the Jeweller, and spent $25,000 on a necklace – then highlighted the plight of West African children mining precious stones on ‘Diamonds from Sierra Leone’ (Source: Bainbridge 2007, np link).

Five years later, he appears on national television to show off his new diamond teeth (Source: LaTour 2010, np link).

I don’t get how Kanye makes a song like this and then buys [his wife] Kim [Kardashian] a HUGE diamond engagement ring, talk about hypocritical (Source: AJEJED7 2014, np link).

kanye is a hypocrite, he wears a muthafu**in diamond mask at his concerts, you can’t argue with that (Source: FixedChamp 2014, np link).

It’s filthy rich people like Kanye that buy diamonds so why does he need to lecture us on the shit in Sierra Leone (Source: roloug95 2014, np link).

Where did those diamonds come from? If he knows, he hasn’t said. He also hasn’t been asked. Kanye, where did your diamonds come from? Are they clean, or did the boy who inspired you to win a Grammy mine your teeth for you when he still had arms? The fact that Mr. West has not spoken to this raises suspicion, and the fact that the media has not asked the question speaks volumes to its efficacy. When a man makes a song about an issue then acts against his own message, it may lead some to think the issue no longer exists. There is still awareness to raise; people are still dying for that bling. Fame does not automatically make one an activist, but taking up a cause comes with responsibility. Mr. West, tell the world where those diamonds came from (Source: LaTour 2010, np link).

they are lab made diamonds, YA TURKEY (Source: Castellanos 2014, np link).

Most diamonds are lab made now. So Kanye isn’t a hypocrite like you think he is (Source: Chenny 2014, np link)!

He’s against conflict diamonds, diamonds from slaves in conflict zones, aka blood diamonds. He isn’t against all diamonds. He’s just asking that people buy conflict-free diamonds (Source: josephalan4 2014, np link).

Urging individualized action as a redemptive response to global suffering, ‘Diamonds’ is thus, in one sense, a typical text within recent media attention on blood diamonds, ultimately advocating little beyond ‘conscientious consumerism.’ So doing, ‘Diamonds’ champions political strategies that bear little in common with political activists across the world who are engaged in anticapitalist struggles for solidarity against the labor practices of multinational corporations, unfair international trade practices across the global North and South, and World Bank and IMF structural reforms that are instrumental in enabling the conditions for human rights atrocities in impoverished developing nations (Source: Mukherjee 2012, p.125-6).

West’s Diamonds track typifies [a] sense of split-ness … through acknowledging the connections between those mining the diamonds to those wearing them, and to Pan-African experience. The track is ‘an extraordinary and powerful recognition of the interconnectedness of struggles’ and is part of his argument that West’s work forges a ‘critical Black conscious-ness’ … West, in this ‘bold political statement’ … is able to map out the international flows of geo-politics, trafficking and consumption and write Black expectation and experience into it. As West articulates in verse one of ‘Diamonds from Sierra Leone – Remix’: ‘How when I know what a blood diamond is? / Though it’s thousands of miles away / Sierra Leone connects to what we go through today / Over here it’s a drug trade, we die from drugs / Over there they die from what we buy from drugs’ (Source: Gardner & Jennings 2020, p.151-2).

[Interviewer] Sway: So you come into that [blood diamond trade] knowledge and put that in the remix, but you still wear a lot of diamonds yourself. What’s the logic behind that? West: How are you a human being, would be more of the question, like, ‘How are you still human when you know what’s going on? How do you still wear what it took your whole life to get?’ Sway: Someone from the outside might say, ‘There he goes again,’ and say that that’s borderline hypocritical. West: Yeah, a whole part about being a human is to be a hypocrite. They say that if you’re an artist you have to stand for this, and they try to discredit you. Like they’ll try to discredit Dr. King or Bill Cosby or Jesse Jackson ’cause they say that they saw them with a woman or something.* So what does that have to do with what Cosby’s TV show meant for us, what it meant for the black image and meant for our esteem, like ‘Damn, we could do that, we don’t have to be like “Good Times” all in the projects’? What does that take away from Martin Luther King, from what he did? Sway: Do you admit to being self-conscious? West: How could you be in this situation with this amount of pressure and this many people looking at you, waiting for you to show them a magic Houdini trick or a David Blaine, waiting for you to not make it out of your chains when the casket goes into the water, and not be self-conscious? How could you not be scared when you step out on that stage? How can I not be scared on the second album? How could I not be scared when I dropped ‘Diamonds’ and there’s people who say, ‘I don’t like “Diamonds”’ (Source: Anon 2005a, np link: *Cosby was convicted of sexual assault in 2018).

I’m gladd some1 at least put something somewhat out about Sierra Leone! people need to be aware of whats going on over there … but he doesn’t actualy care about Sierra Leone … if he did why would [h]e always be wearing so much diamonds?? god i hate rap (Source: Pixxie 2005, np link)!!

If someone can show me how his lyrics have anything to do with Sierra Leone, I would appreciate it. (Source: Cswayzer1 2012, np link).

[W]hat Kanye raps about is the vanity we all caught up and build to see where are wealth comes from the evil means used to get it because we all caught in vanity (Source: Ncube 2014, np link).

the song didn’t get close to speaking about the atrocities that were committed in Sierra Leone. He begins the video leading you to think that he is going to speak about the issues over there. But then he starts talking about himself. Perhaps I don’t understand (Source: Cswayzer1 2012, np link).

The video is great, but the song has nothing to do with Sierra Leone. Like so many rappers, it seems he’s just rapping about himself. Real deep there, man (Source: ApollyonCrash 2005, np link).

I’ve found that most videos don’t have anything to do with the songs. Haven’t you? The imagery is very striking, nonetheless. And he says he isn’t gonna even [give] his chain back (Source: Nurasake 2014, np link).

this is the most disgusting sh*t I’ve ever heard. To call a track diamonds from Sierra Leone, shoot the video in Prague, and talk about nothing but yourself? Yes the beat is good, the chorus is amazing, but F*CK… WAKE UP. Malcolm X would slap this guy. Hard (Source: XArcane 2012, np link).

Perhaps [Kanye]’s more clever than I’m giving him credit to be and there’s some ironic tone to this song I’m not seeing, but I highly doubt it. Even if the song is put out in a sarcastic tone, the majority of people listening to this song aren’t going to get it, and the song won’t raise any awareness to the crisis in Africa. Overall, this is false advertising to the greediest degree (Source: Bella_x 2006, np link)

This does not … however the remix does (Source: The Notorious K.F.L.O. 2014, np link).

I’ve always loved [the remix] version more than the original. He really brings to light the ongoing issue of blood diamonds. If only this was paired with the music video (Source: Reekidfan1 2024, np link).

[The original] radio friendly track … [is] sugar-coated ‘revolution’, but the remix featuring Jay Z is an excruciatingly haunting yet masterful piece of work (Source: Ahmad 2005, np link).

I think Jay’s verse was mid. He didn’t even address the subject of the song. He took this song and opportunity to address a devastating situation where kids were forced to mine for diamonds yet Jay decides to rap about his own riches…. Imagine being stuck mining in Sierra Leone and you find out someone was making a song about your situation but then it’s just Jay rapping about being a ‘business man’ (Source: Dre B 2025, np link).

But [the original video] still made awareness a lot of people googled the situation and are now made aware (Source: Brantley 2014, np link).

I don’t need to be more aware of this cuz its not my fault, its the rich peoples fault so kanye, you are an idiot (Source: FixedChamp 2014, np link).

at least you all know what Sierra Leone is now, because he used his power to draw attention to a huge issue (Source: lilmike576 2007, np link).

When Kanye West released ‘Diamonds from Sierra Leone’, I felt like my two worlds were colliding. I’m an avid hip-hop fan and in 2005 … Kanye West, put the name of my country on the title of his first single! … I’m a fan of lyrics and from the little I’d heard I’d gathered that he was using the conflict diamonds issue as a metaphor for the inner politics that was happening at the time, at his music label Roc-a-Fella, ‘THE R.O.C.’ Yet it was the video that really surprised me, the eerie intro to the video starting with children in the diamond mines depicted with dilated pupils to emphasis the eyes response when attracted to something, hearing Krio in the narration of a hip-hop video (though my cousin argued the accent was off), the journey of these precious stones from the ground of Salone to the Jewellery shops of Europe and even the message in the closing credits ‘Please Buy Conflict-free Diamonds’ … I mean school teachers were playing the video in Geography classes! However more was to come when he released the remix with Jay Z with content more specific to the plight of children working in mines to dig stones out the ground. Overnight the blank expressions I would get when I mentioned where I was from were now replaced with expressions of intrigue and wonder. Ignorance was bliss until you decide you want to learn something new and if we choose to close our eyes when we’re afraid of what we might see, it’s because we’re comfortable in our own lack of light. … Being a fan of hip-hop you are always going to be conflicted and Kanye is the epitome of that back then as he is now. He highlighted and generated more awareness about conflict diamonds and now people knew Sierra Leone is a country in Africa and not an island off Portugal. This was not to be the last time I would hear Sierra Leone being used in lyrics for songs. The flood gates opened and now every hip-hop artist had license to use Sierra Leone as the new slang to refer to the diamond jewellery that they wore (Source: Sesay 2019, np link).

As a Sierra Leonean, this is a masterpiece. This song is amazing and the message Kanye is sending is very deep. Love the Krio intro 🇸🇱 (Source: @CHIEFBAIBUREH1 2021, np link).

As a Sierra Leonian, that isn’t a real Krio accent (Source: @moi8387 2021, np link).

I’m proud to be a Sierra Leonean. Thank you Kanye for recognizing my country. We have the best diamonds in the whole world. That is why we fought for 11 years due to greedy politician and western influence (Source: Felix 2019, np link).

This is talking about blood diamonds from Sierra Leon. That’s not a good that (Source: Ashlesser 2020, np link).

I think he was saying they have the best diamonds which is why people are enslaving them and making them mine them and he’s proud of them fighting back against it (Source: FlowerTower 2020, np link).

KANYE WEST can go suck a d@ck… becuase he’s all about defending AFRICAN children being forced to excavate diamonds, but it’s all cool if ASAIN children are forced to make shoes or other things like that (Source: meyers 2014, np link).

are you stupid? Kids in Africa are getting murdered of Diamonds, Genoiced!!!! Aint no body in china dying over NIKES fool (Source: Jack 2014, np link)!

it clearly says DIAMONDS of Sierra Leone and not Shoes of Sierra Leone (Source: Monteiro 2014, np link).

I think the fact that you even brought that up shows that the message in this song is doing exactly what its suppose to do, make you REALLY think about things. We are all in some form of enslavement when you REALLY think about it. Wether its the Asain people to sweatshops, Black Children to Diamond mines, or even our own people to our goverment and rediculous materialistic values (Source: Jones 2014, np link).

conflict free evereything in 2024 (Source: Wilberger 2025, np link).

This song is so cinematic, straight out of a James Bond car chase scene (Source: @broskiezISMYGAMERTAG 2021, np link).

I was just thinking, this could be the theme of a James Bond movie xD (Source: @jeroenvandervelde3833 2021, np link).

Outcomes / Impacts

In 1998 a British campaigning organisation, Global Witness, first told the world about conflict or blood diamonds: stones that were being sold by paramilitary groups to help to fund their wars. … Alex Yeardley, [campaign coordinator at] Global Witness, says: ‘We were always trying to get to the hip-hop crowd on this. There seemed to be this screaming contradiction; you have people who’ve come out of repression, come out of the long history of the civil rights movement, and there they are, sporting bling, bling, bling. They’re very proud of their African roots, and yet they had no concept, no idea of what was going on. … When we first tried to launch the campaign, we went to one paper, and they said, “Have you got any celebrities?” We wrote to several people and we contacted various pop bands that we had connections to. But all we were getting was, “It’s all a bit political, it’s all a bit too difficult to grasp.”‘ While the odd socially aware musician wrote lyrics about blood diamonds, such as the veteran Chicago folk-soul singer Terry Callier and the British rapper Ms Dynamite, the bling crew were slow to get on board. All that changed in summer 2005 when Kanye West performed at Live8. Yeardley, who was watching, recalls his shock. ‘I was like, “Did he just sing a song about Sierra Leone diamonds?” ‘ (Source:Batey 2007, p.24).

More folks have … become more aware of ‘conflict diamonds’ because of Kanye West’s hit song (Source: Cho 2008, np link).

[It] makes us take an honest look at ourselves and ask: Is my fascination with diamonds contributing to the violence in Sierra Leone (Source: Brown 2005, np link)?

This song came out when I was about 9 or 10 and to this day I don’t buy or wear diamonds. When my ex and I got serious I told him that if he ever proposed to me, I would say no if he bought me a diamond ring (Source: FlowerTower 2021, np link).

+17 comments

When Raquel Cepeda first learned of the conflict in Sierra Leone back in 2001, she was working as the editor in chief of Russell Simmons’ now-defunct One World magazine. In keeping with the publication’s theme, she would find places around the globe where hip-hop had taken a foothold, and Sierra Leone’s burgeoning scene grabbed her attention. But almost immediately, she knew a mere magazine article would not do the country’s story justice. After all, this was a nation just emerging from a savage 11-year civil war – a conflict fueled by the diamond trade – and was in the early stages of recovery, picking through the rubble and trying to rebuild. And seemingly no one was paying attention. ‘I felt that Sierra Leone was more than an article, because I saw these fascinating parallels,’ Cepeda said. ‘It was formed by freed slaves, and just at the time hip-hop started to become commercially successful here in the United States – in 1991 – [the Los Angeles district of] Watts was burning, and this bloody civil war was beginning in Sierra Leone. So as the conflict was ending, and the aftermath was everywhere, I felt like it would be an interesting social experiment to have some rappers go there as goodwill ambassadors. Because hip-hop has affected every crevice of the world, and I wanted rappers to know that.’ And so Cepeda decided to make a documentary that would do just that: show rappers – and hip-hop fans – the connections between hip-hop and the Sierra Leone conflict. While her film does focus on the role music has played in the country’s recovery – there’s a vibrant hip-hop scene in the capital city of Freetown, highlighted by artists like Daddy Saj and Jimmy B – it’s more concerned with the implications that came with the genre’s bling obsession. She decided to call the film ‘Bling: A Planet Rock,’ because the insatiable thirst for diamonds was indirectly affecting the war in Sierra Leone (Source Montgomery 2006, np link).

Rappers KANYE WEST and PAUL WALL have teamed up to help educate their peers about ‘bling’ they shouldn’t be buying. The pair joins the likes of JADAKISS and RAEKWON in a hard-hitting new documentary about Sierra Leone’s ‘conflict diamonds’, which are reportedly mined from quarries run by ‘murderers and rapists’. West and Jadakiss agreed to speak out about the terrible trade in RAQUEL CEPEDA’s film BLING: A PLANET ROCK, while Wall and Raekwon accompanied her to the African nation to see civil war atrocities at first hand. Cepeda tells MTV News, ‘I felt like it would be an interesting social experiment to have some rappers go there as goodwill ambassadors. Raekwon really bonded with everyone he met in Sierra Leone. He didn’t know what to say at some points, because what he saw left him speechless.’ The documentary, which also features interviews and performances from Sierra Leone’s top rappers, follows the story of militant group the Revolutionary United Front, which launched a bloody bid to take over the nation’s diamond mines in 1991 (Source: Anon 2006, np).

In early 1991, … the Revolutionary United Front launched an insurgence against the government in Sierra Leone, attacking villages and committing unspeakable acts of barbarism against women and children. The militants hoped to throw the nation into a state of chaos, taking over the nation’s diamond mines and using their riches to purchase drugs and weapons from neighboring nations. These diamonds became known as ‘conflict diamonds’ – or blood diamonds – the same rocks Kanye West raps about in his song ‘Diamonds From Sierra Leone’ (Source Montgomery 2006, np link).

‘[Bling: A Planet Rock] is not intended to make people stop wearing diamonds, because if we boycotted them, it would impair the fragile economy of Sierra Leone and would end up hurting these people,’ Cepeda said. ‘It’s nobody’s fault – the rappers, anyone – if they don’t know they’re wearing conflict diamonds. So we wanted to raise awareness about the whole issue. We wanted people to bling responsibly. We want rappers to rap about how it’s cool to wear cruelty-free diamonds. And Kanye helped with that.’ West is interviewed in the film, as is Jadakiss, though neither artist was able to make the trip with Cepeda to Sierra Leone due to scheduling conflicts. But thanks to funds secured from the United Nations and VH1, she was able to secure three other hip-hop figureheads that knew very little about the country but were willing to learn: Paul Wall, Raekwon and reggaetón star Tego Calderón. … ‘Up until I heard Kanye’s song “Diamonds From Sierra Leone,” I had never even heard of the country,’ Wall said. ‘But once I did, I wanted to find out more, and I wanted to try to help out. So we went to Sierra Leone – me, Raekwon and Tego Calderón – and it changed our lives. We saw the diamond mines and the amputee camps, and it was hard to believe that especially in 2006, people can be living like this. ‘When we were over there, it shocked and kind of embarrassed us as jewel wearers, but the people over there told us not to stop wearing them,’ he continued. ‘The thing is, that’s how people eat. Even to this day, there’s a large percentage of illicit diamonds in the marketplace, even though the conflict in Sierra Leone is over. So you want to be careful and get them through the proper channels. I know I’m trying to do that now’ (Source Montgomery 2006, np link).

Diamonds [from Sierra Leone] has been a headache for its maker … Negative reactions from West’s core fanbase stung him into dropping four of the album’s more outre songs, including one that features John Mayer and a harpsichord, and replacing them with more conventional hip-hop tracks. Never one to understate his case, he proclaims on the crunching, martial Crack Music: ‘This is black music, ni**a!’ … All this is saying is, OK I see now, the ‘hood does not quite want Shirley Bassey yet, so let me still give them this.’ Crack Music was made after Diamonds. After black people were like, ‘I don’t know about this one.’ It was like me reaching too high for the cookie jar (Source: Lynskey 2005, np link).

Fellow rapper Lupe Fiasco raps over [Diamonds from Sierra Leone‘s] instrumental on [his track] ‘Conflict Diamonds’, which was released on his second mixtape Fahrenheit 1/15 Part II: Revenge of the Nerds (2006). The song’s lyrics feature Lupe Fiasco discussing the illegal diamond trade in Africa, mostly referencing the western area of the continent. For the song’s conclusion, he raps: ‘Props to Kanye, I call it ‘Conflict Diamonds” (Source: Wikipedia nd, np link).

Not all famous people have to be activists; not every action must be political. When a musician wins a Grammy award for a song about the blood diamond issue, however, it is fair to expect consistency. Mr. West won that award for his song ‘Diamonds From Sierra Leone’ in 2006 (Source: LaTour 2010, np link).

West has become increasingly vocal on political matters of late and recently used the video for his ‘Diamonds From Sierra Leone’ single to highlight the suffering caused by conflict diamonds and the human rights abuses that occur in mining them. … The rapper-producer was taking part in a telethon for the victims of Hurricane Katrina when he spoke out about the treatment black people in the disaster … ‘I hate the way they treat us in the media, when you see a black family it says they’re looting when you see a white family it says they’re looking for food,’ said West before personally targeting the President … ‘George Bush doesn’t care about black people,’ he declared adding that America is set up ‘to help the poor, the black people, the less well-off as slow as possible’ …. West then praised the Red Cross’ efforts saying they were doing everything they can. NBC, the network that aired the programme, quickly distanced itself from West, declaring he had departed from the scripted comments that were prepared for him (Source: Anon 2005b, np link).

Perhaps his recent insight about blood diamonds in Sierra Leone aided in leading him on in his political crusade against racism. One way or another, his words deeply struck the people of the United States, including George W. Bush himself. In separate interviews with Matt Lauer in November 2010, former President Bush and Kanye West revisited the moment after five years, a moment which Bush cites as ‘one of the most disgusting moments in [his] presidency.’ During West’s interview, the artist refused to admit regret for calling the situation out as a race issue but said, regarding Bush, ‘I empathize with the idea of being pegged as a racist,’ before being cut off by an impatient Lauer trying to extract an apology (Source: Dudding 2011, p.30 link).

[A] study commissioned by Inhorgenta, one of Europe’s leading trade fairs for jewelry, watches, and gemstones, and the consulting firm Deloitte … [found that] many consumers are very aware of sustainability and environmental impact – if you take all age groups together, more than 40 percent pay attention to this when buying a watch. Among the younger ones, the figure is even slightly more than half. And they want to know exactly: Whether ethical standards are adhered to in the procurement of raw materials, what the working conditions are like in the extraction of the materials or to what extent the extraction of raw materials has an impact on the environment. This is a customer group that is usually well informed before buying and has probably also been sensitized by pop culture, be it the Kanye West [2005] hit ‘Diamonds from Sierra Leone’ or the [2006] film ‘Blood Diamond’ starring Leonardo DiCaprio, which addresses the illegal trade in blood diamonds in Africa (Source: Gerstmeyer 2021, p.29).

Since the film Blood Diamond came out in 2006 – the year after Kanye West’s Diamonds From Sierra Leone was nominated for most outstanding music video – blood or conflict diamonds have become front of mind for consumers. Those invested in a diamond purchase want to know their diamonds weren’t mined in a war zone and sold to finance an insurgency or the activities of a warlord. They expect every step of the supply chain to be recorded, as reassurance that no human rights abuses occurred along the way. Lucky for them, it’s available, thanks to the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS). In 2000, southern African diamond-producing states met in South Africa’s Kimberley to respond to the terrible human rights abuses in parts of the continent where rough diamond production is common. The United Nations General Assembly came on board, supporting the creation of an international certification scheme for rough diamonds. By 2002,negotiations between governments, the international diamond industry and civil society organisations resulted in the creation of the KPCS,which ensures the origin of a diamond is verified through every step of the distribution chain. It’s estimated that less than 1 per cent of diamonds on the world diamond trade are conflict diamonds – a reduction from approximately 4 per cent before the KPCS was established. Ethical diamonds go so far as to carry a Kimberley Process Certificate, which is verified every time a diamond changes hands. ‘It’s like a birth certificate – a trace process from mine to site holder to diamantaire to the company thatpolishes those stones,’ says Melissa James, executive officer of Diamond Guild Australia (Source: Anon 2018, p.4).

Carson Glover, a spokesman for the World Diamond Council, says that the flood tide of interest [in Blood Diamonds] – spurred by [Di Caprio’s Blood Diamond], West’s [Diamonds from Sierra Leone] video, Zoellner’s [The Heartless Stone: A Journey through the World of Diamonds, Deceit and Desire] book and the History Channel documentary ‘Blood Diamonds,’ which airs Dec. 23 – provides ‘an opportunity to educate the public about what has happened since [the 1990s]. For us it’s a chance to talk about the Kimberley Process.’ But [Douglas] Farah, [a] journalist who wrote about the link between diamonds and Osama bin Laden, says that the diamond industry’s worst nightmare is not bloodshed but the perception of bloodshed, and that the public relations response to ‘Blood Diamond’ has been far swifter than its reaction to the events themselves. ‘They’re doing the minimum to avoid a boycott,’ Farah says (Source: Davidson 2006, np).

Conflict diamonds are far rarer than they were just a few years ago. … Sierra Leone is at peace; its war ended in 2002. But all this delayed outrage over conflict diamonds still can be useful in the battle for hearts and minds. Activists stop short of calling for a diamond boycott but want to put diamond retailers on notice by urging consumers to ask aggressively about the origins of their stones. But how to spark all this consumer concern when only one per cent of the stones are considered conflict diamonds? Question the little number. Global Witness, the British advocacy group that first alerted the world to the problem in 1998, now says that conflict diamonds are part of a controversial stream of stones that also includes smuggled diamonds and diamonds mined in abusive labour situations worldwide. Put all that together and the flow of controversial diamonds, says Global Witness, really is more like 20 per cent. ‘It all boils down to definitions,’ Alex Yearsley, campaign co-ordinator for Global Witness, wrote in an e-mail. ‘We’re not attempting to conflate the issue’ but ‘the issue of illicit (diamonds) is intimately connected to conflict diamonds.’ The United Nations disagrees. It strictly distinguishes between diamonds smuggled in peacetime and diamonds mined by rebels during conflict. … To head off damage to the diamond’s mystique, the industry has touted one per cent as proof of its success in largely eradicating conflict diamonds … Conflict diamonds came mostly from the wars in Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Sierra Leone, the country depicted in Blood Diamond. Rebels press-ganged miners in those countries into searching for the stones. While those wars raged, rebel stones made up to 15 per cent of the world’s diamond trade. With the wars now largely ended, governments are attempting to legitimize their national diamond trades through a global regulatory system called the Kimberley Process. The Kimberley group, made up of 71 nations, says the flow of conflict diamonds has slowed to a trickle. They are coming from rebel-held areas of Ivory Coast, skirting a UN diamond embargo there and smuggled through neighbouring Ghana or Mali. The UN says the value of those Ivory Coast conflict diamonds is about $23 million, far less than one per cent of the production of rough diamonds, which is about $12 billion a year. Under the Kimberley system, governments are supposed to be able to certify their rough diamonds from the time they are mined to the time they arrive at a cutting and polishing centre. From there, diamond suppliers like the De Beers Group, which produces 40 per cent of the world’s diamonds, are supposed to guarantee that their stones were sourced through the Kimberley Process. It takes the diamonds only a matter of weeks to move from mine to market. Activists say the Kimberley Process is deeply flawed because it is not a treaty but merely a commitment without enough oversight to ensure countries really are regulating their diamonds. And that means no number can be trusted (Source: Duke 2006, p.19).