followthethings.com

Health & Beauty

“The First Ever Pacemaker To Speak For Itself“

Undergraduate coursework made and recorded by Jennifer Hart

Images of the pacemaker and packaging submitted is in the slideshow above, the song is embedded below.

The students’ first task in the ‘Geographies of Material Culture’ module at the University of Exeter is to make a personal connection between their lives and the lives of others elsewhere in the world who made the things they buy. These are the people who help you to be you, followthethings.com CEO Ian tells them. So choose a commodity that matters to you, that’s an important part of your identity, that you couldn’t do without. Think about its component parts, its materials, and what properties they give to that commodity and your experience of ‘consuming’ it. Student Jennifer Hart feels guilty about the conflict minerals in her mobile phone. Then she finds that the heart pacemaker her mum is having fitted also contains those minerals. It’s a lifesaving operation. How can she reconcile her mum’s suffering and that of these minerals’ miners? How best can she express her feelings about this technological object? By making a pacemaker that knows what she knows, feels what she feels, and can sing about it. A pacemaker that can express a huge thank you.

Page reference: Jennifer Hart, J. (2014) The First Ever Pacemaker To Speak For Itself. followthethings.com/pacemaker.shtml (last accessed <insert date here>)

Estimated listening & reading time: 10 minutes.

The commodity

The song

The writing

The mobile phone industry holds dark secrets of exploitation and funding war through the mining of conflict minerals such as lithium ion and coltan in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Coltan is a mineral which goes into tantalum capacitors; a type of electrolytic capacitor used in many electronic goods… Phones… Laptops…

‘Coltan…is…a crucial component of the microchips found in all digital technology…as well as a host of other electronic devices, including hearing aids and pacemakers’ (Smith and Mantz, 2006, p74).

I was stunned by the ‘including…’. Until then, the exploitation of coltan miners was purely to feed a fetish for ‘unessential’ electronic commodities. It would be difficult for me to live without my phone, but it’s not life-saving, like pacemakers are. My mum was having a pacemaker fitted in a few weeks.

Before I knew that her pacemaker contained coltan, I was worried about what she would go through. ‘I hope she’ll be alright’. ‘I hope she won’t be in pain’. ‘I hope she won’t suffer’. It never entered my head that people mining the minerals that would make it work might suffer too.

Thinking about the coltan in my mobile phone, I could feel guilty about this suffering. But with my Mum’s pacemaker, it felt like swapping the miner’s health for my mum’s health. This frightened me. It’s almost a case of ‘kill or be killed’. But, I thought, she and they were connected by the need for pacemakers. She needs to survive. The miners need the income.

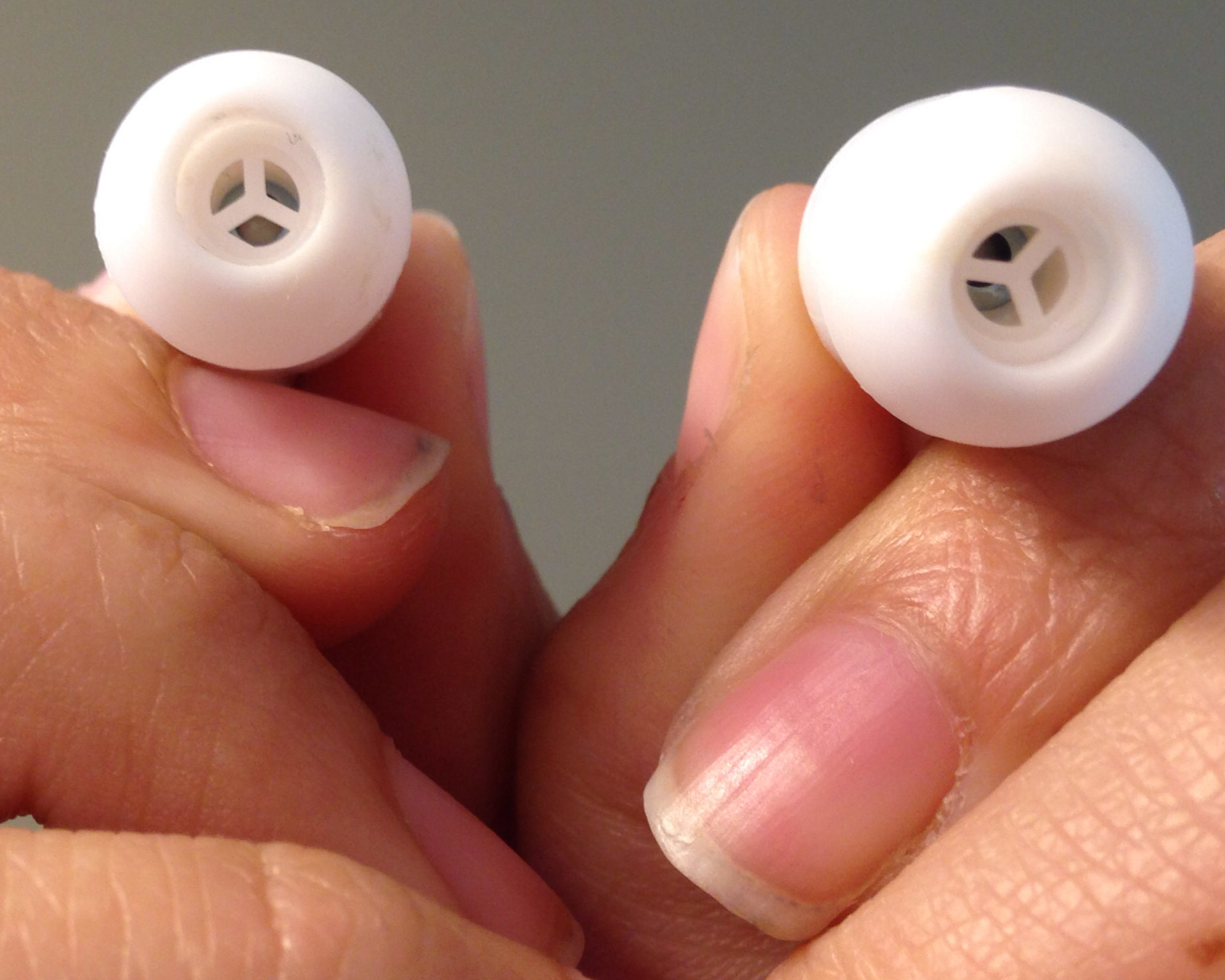

I wondered how the miners would feel if they knew their struggles were not purely feeding capitalist greed and consumer desires for the latest phone, but also saving lives. I wanted to try and do something to thank them. I often struggle with trying to explain how I feel and interact with things. How I feel about this piece of technology is hard to describe on paper, but was easier to express through music. I wrote, performed and recorded a song. I then put it on that mini MP3 player, which I packaged up to look like a pacemaker. This pacemaker could talk – sing – about its life, the lives it touched, and the differences it had made.

I made this commodity because I wanted something to speak out in a way that I could not. The song describes my moral dilemma, informs listeners of the miners’ exploitation, and thanks the miners for helping to save my mum’s life. This was a a way of giving a voice to the product it means to represent. The packaging brings the pacemaker player, the headphones and a leaflet of lyrics together. It’s not supposed to be ‘read’, but to give the person who receives it curious object to open, discover, put together … not only to learn what I had learned, but to feel what I felt about.

Having got to this point, I don’t want to ignore the issues raised, I want to help change them for the better. I know what’s possible. Another example I’ve worked on for this site is the conflict-free Fairphone.

My Mum’s pacemaker displays not only the lives that are in things, but that things give life.

The operation was a success. She feels better than ever, with a machine in her chest to help her live. Coltan helps her body to function. It’s an essential ingredient. I asked her how she felt about this:

I am grateful for everyone who helped make me better. All the people who have researched, produced, mined and made the pacemaker and operated on me have allowed me to have a relatively good quality of life with this fifty pence sized miracle. Without these people, I would have died.

In the beginning, you think of yourself. Then you think about what the surgeon has told you is the problem, then the solution. Very rarely do we think about the people who get these components together; the miners for instance. All you really think is ‘thank god for the man who saved my life’ – the surgeon. You do not think of the other elements, and maybe we should.

It’s humbling. We don’t think about where components come from. These people deserve a lot more. I wonder if they realise how their pain is helping someone live a normal life.

Coming from a nation of plenty, you don’t realise what other people go through, really. Without these people and this element that they mine, why don’t we think of them? We need to find out more about it. I have been given no information about my pacemaker, other than what make it is and how it is set up and how it works.

Page originally created as coursework for the ‘Geographies of material culture’ module at Exeter University. Edited by the author as part of a nicely paid followthethings.com internship (last updated June 2014).

Sources

Smith, J. & Mantz, J. (2006) Do cellular phones dream of civil war?: the mystification of production and the consequences of technology fetishism in the Eastern Congo. in Kirsch, M. (ed) Inclusion and exclusion in the global arena. New York: Routledge

Image credit

Header: Woman receiving surprise being impressed and speechless from happiness (https://www.freepik.com/free-photo/woman-receiving-surprise-being-impressed-speechless-from-happiness_21403704.htm#fromView=search&page=8&position=16&uuid=3cc39deb-730c-42f0-bbb2-32b63a8b7087) by cookie-studio (freepik)

![]()