followthethings.com

My shopping bag

“followthethings.com Shopping Bag“

A limited edition run of 5,000 reusable plastic shopping bags designed by Daisy Livingston & Aidan Waller and distributed freely to support the launch of the followthethings.com website.

The last bag was given away in 2016. Still in circulation.

The followthethings.com launch team are keen to create some merchandise to promote their website. Intern Daisy had submitted a printed cotton bag she had had manufactured in China as coursework for Ian’s ‘Geographies of Material Culture’ module. It was the most original, imaginative coursework he had ever seen. That’s because it wasn’t just about the geographies of material culture, it embodied them, materialised them. Ian hired Daisy as an intern and asked her to design and order some reusable shopping bags for followthethings.com’s launch. Fellow intern Aiden helped out. These needed to be just like the ones that we used for our supermarket shopping at Sainsbury’s, Tesco, ASDA, Morrisons. They were pretty standard in their construction. But where were they made? From what materials? How could you find out? What could you find out about the pay and conditions of the people who made them? Quite a bit, it turned out, if you had your own made in the same places. What insights could this privileged business-to-business customer perspective provide? And what could happen after you put these mischievous shopping bags into circulation? Especially when the meaning of ‘shopping’ in the project – and on the bags – was double: i.e. both ‘to seek or examine goods, property, etc. offered for sale in or by’ and ‘to behave treacherously toward; inform on; betray’ or ‘to give away information about’ those goods, property, etc. (Anon nd). Once you read about our bag, you can apply its lessons to the ones that you have…

Page reference: Ian Cook et al (2024) followthethings.com Shopping Bags. followthethings.com/followthethings-com-shopping bag.shtml (last accessed <insert date here>)

Estimated reading time: 21 minutes.

The story

We need to develop forms of critique that inspire hauntings, feed feelings, come alive, leap out and grab us, … that are not just about vital materiality but are themselves vitally material.

Ian Cook & Tara Woodyer (2012 p.238).

1. Introduction

In 2011 the team that created the original followthethings.com website designed, commissioned, followed and distributed 5,000 reusable shopping bags that were made in China. We wanted some followthethings.com merchandise to help promote the site when it launched. We didn’t want only to think about the lives of things, but with them too. We loved the double meaning in English of the verb ‘to shop’. It wasn’t only a matter of going to the shops to buy things, it could also mean betraying the origins of things, like you might ‘shop’ a person to the police. And our project wasn’t only about other people’s trade justice activism. We wanted to create our own too. Our website was one example (see Cook et al 2017). The bags were another. The approach we took is called ‘critical making’ (see Cook et al 2014, cf Ingold 2007, Hawkins 2011, Last 2012). But what could we learn about trade geographies from this making process? And what could we do with the bags once they were made?

Check out the other examples on our site whose actvism has involved having things made -> here.

2. Why make bags?

followthethings.com is a massive collaborative project ‘orchestrated’ by me, Ian Cook. Undergraduate students taking my ‘Geographies of Material Culture’ module at the University of Exeter in the UK have researched the first drafts of most of its ‘compilation’ pages (i.e. the ones full of quotations) and most of its ‘follow it yourself’ pages. Over the years, many have been employed as interns to work these compilation pages up for publication on the site. Daisy Livingston was one of the first. In January 2011, she submitted a cotton shopping bag containing some documents as her coursework. She’d had a batch of these bags made in a factory in China. The documents were the shipping documents and printouts of email conversations she’d had with factory. This was the most original, imaginative coursework I had ever seen. I asked Daisy and four other students if they’d like to work with me as interns that summer on a website I wanted to launch soon. I asked her, specifically, to design and order some followthething.com-branded reusable shopping bags. Like the Sainsbury’s and Tesco bags I had at home at the time (see below).

She told me she’d decided where to get her bags made via a website called alibaba.com. So we searched for these supermarket and other reusable plastic shopping bags there, looked through countless pages of product photos, and clicked the ones we recognised. We ended up on alibaba.com pages which named and provided the addresses of factories where they were made. These pages said how much they would cost to make and who to talk to about placing an order. We wanted to design our bag so that it could be easily mistaken for the supermarket bags we knew, using the same kinds of materials (‘pp woven’ plastic, we learned) and colours. We chose a factory based in Shandong, and asked them to make our bags to the exact specification of a ‘pp woven’ bag we knew they had made for Sainsbury’s, with the same orange handles. By placing an order for our bags, we were learning about the sourcing of theirs.

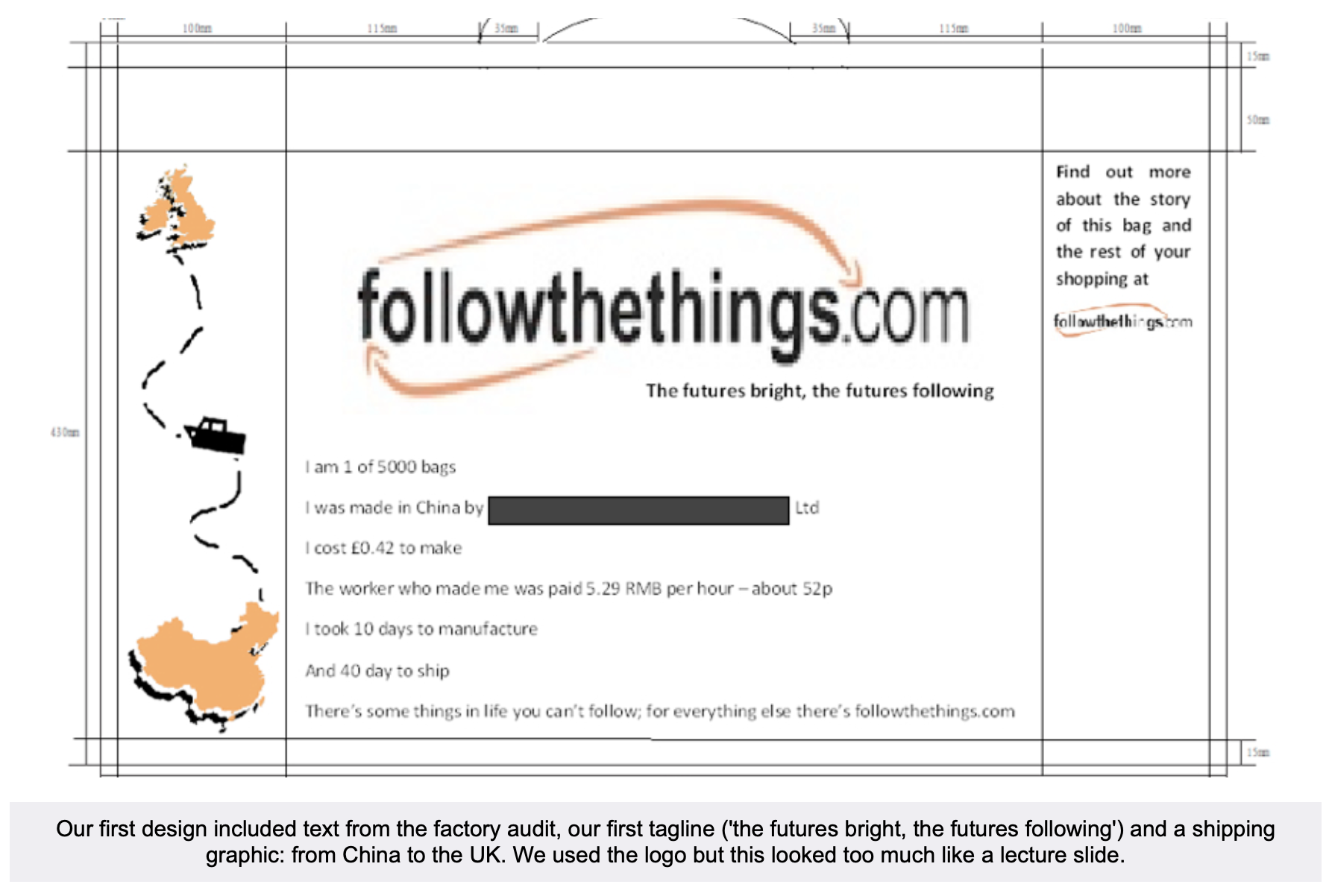

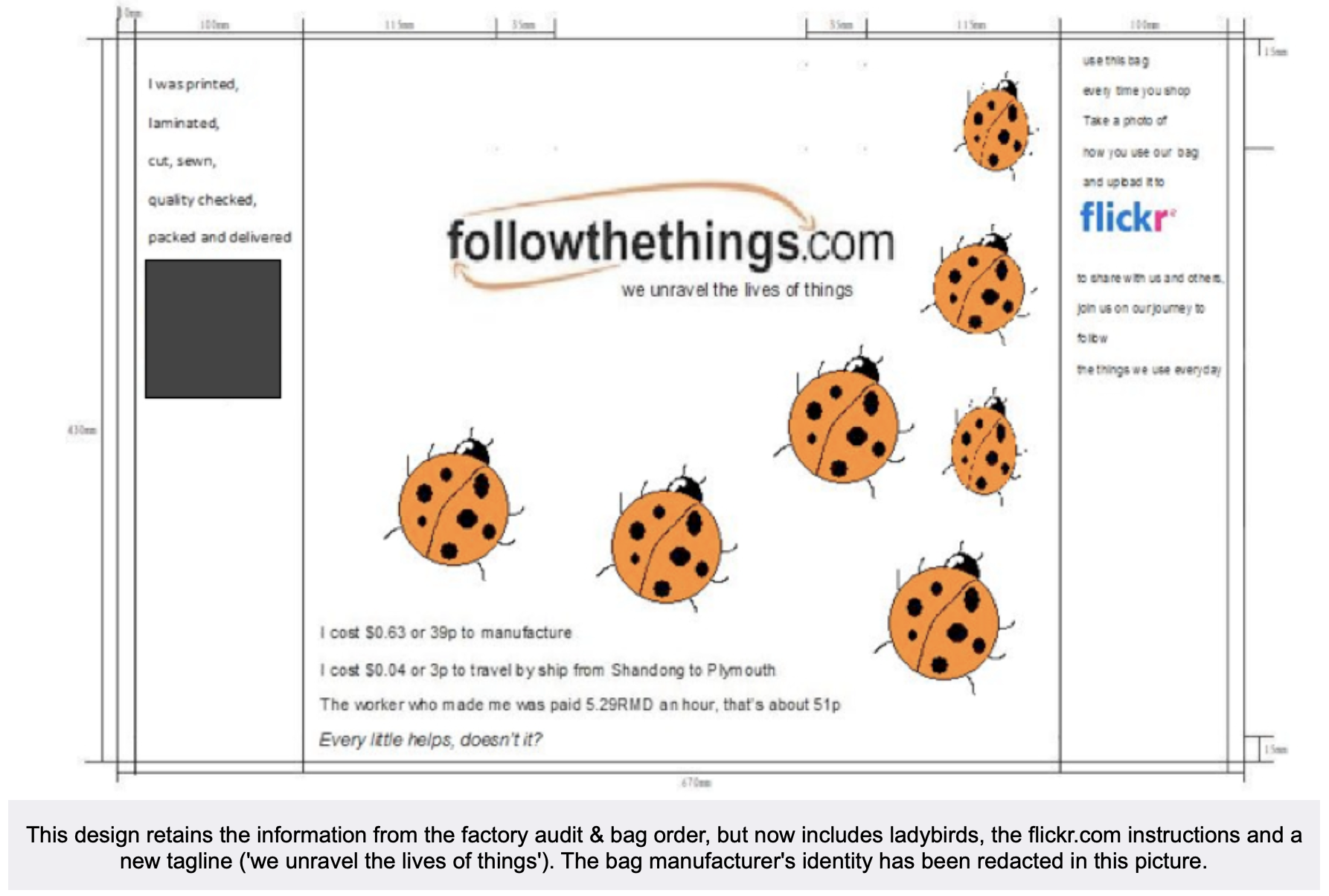

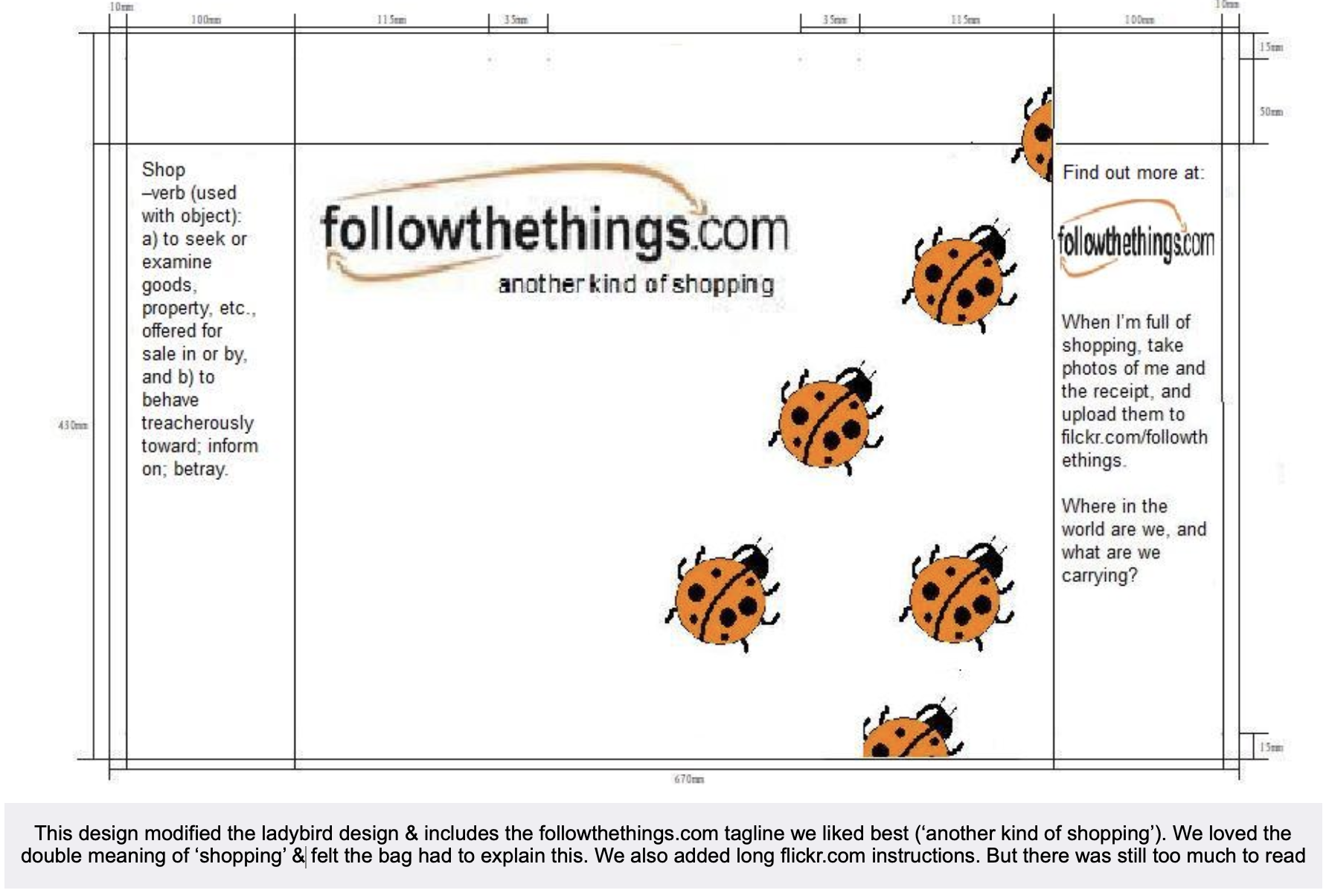

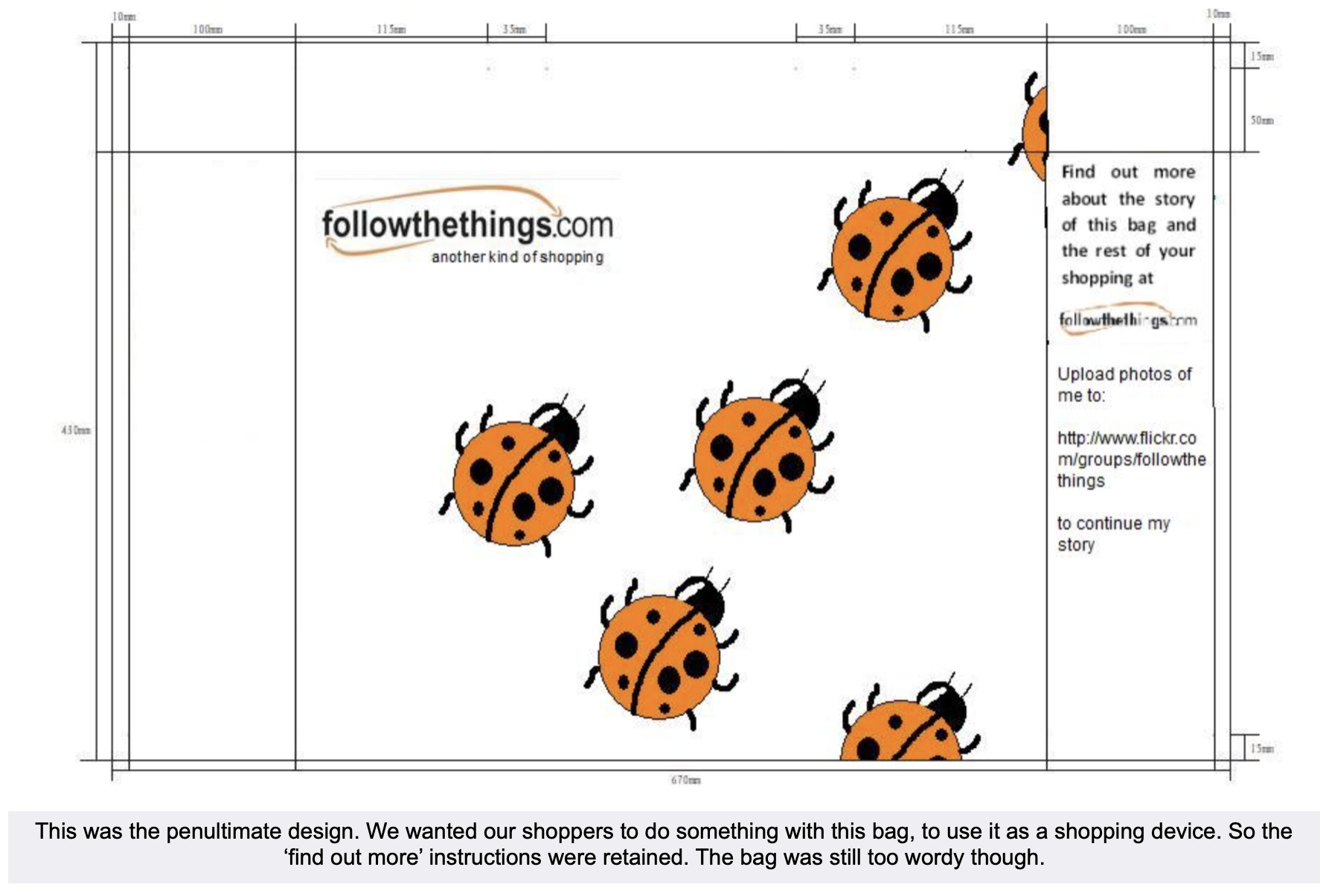

3. Bag design

Our bags were designed in the summer of 2011 by Daisy and fellow intern Aidan Waller. We wanted them to be made to the same specification as our ‘rivals’ not only because we wanted them to be visually familiar to our shoppers, but also because we wanted them to feel physically identical too. The factory emailed us a bag template and asked us to place our design onto it. A reusable ‘pp woven’ shopping bag is made of 5 pieces: 2 handles, a bottom panel, and 2 identical main panels whose central pane is the long side of the finished bag, and whose end panes are half of their side panels. We started to experiment with what our bag could look like. There were a few iterations. We were new to this. We ordered 5000 bags because that was the minimum order.

Watch a video showing trade justice actvism in product design for the Yes Men’s ‘B’eau Pal Water’ prank -> here.

4. Factory conditions

One of the things that you can ask for if you’re having some shopping bags made, or anything else, are factory audits. We didn’t want to find out at a later date that our bags had been made in a sweatshop. So we asked for ethical audit reports. The ones that we were given from the factory were ones conducted according to the Ethical Trading Initiative’s Base Code which sets out minimum wage standards and health and safety conditions. The audits we were sent included photographs that showed particular issues mentioned in the audit report. They showed an emergency light and exit sign, some drinkable water, the coating and cutting workshop, the first aid box, the printing workshop, the sewing workshop, the packing workshop and the place where pallets laden with boxed bags were stacked before dispatch. What was surprising to discover in these audit reports was that this was the factory where Sainsbury’s reusable elephant shopping bag had been made (see above). This was a bag that I had at home! Photos in one audit report showed factory workers sewing its panels together in the sewing workshop and packing the completed bags into boxes in the packing workshop. Unfortunately, we couldn’t use these photos in any academic publications or blog posts because the reports were labelled confidential. For our eyes only. But we included some information gleaned from our order (and from the reports) in our first bag designs (see above).

5. Shipping

When all the bags were made, and the first half of the bill paid for, they were ready to ship. The factory sent us a document called a Bill of Lading. On its we discovered the name of the container ship it would be traveling on: the Cosco Pacific. A ship-spotter had taken some footage of it on the River Elbe in 2011, so this helped us to imagine its size, its journey, and its working conditions.

For trade justice activism that’s about the pay & conditions of logistics workers, check ‘ship my order’ -> here.

We began to track our ship starting at the port of Qingdao using an iPhone app and a website called MarineTraffic.com. This allowed us to follow our bags, live!

Every couple of days, we tweeted where it was and, where possible, any ‘port stories’, stories of labour conditions and others issues at the ports that it passed through and stopped at. So, for example, the Cosco Pacific left Qingdao port on September 19, docked at Yantian (where, for example, crane operators had been on strike in 2007). It entered Singapore Harbour (where, for example, two Bangladeshi port workers had been found alive and dead in a container in 2011). It then sailed along the Malacca Strait, across the Indian Ocean, past the Southern tip of India and Sri Lanka, through the Suez Canal and into the Mediterranean, out into the Atlantic, along the English Channel, to Rotterdam, then Felixstowe (where, for example, the UNITE union were attempting to organise truck drivers operating out of the docks in 2011 and the port was expanding). [By the way, a) no trace now exists of these news stories online, and b) we weren’t trying to find tales of labour exploitation to show the evils of capitalism everywhere our bags went. Rather, these were the tales of working life that make the press and they contained lots of interesting, nuanced, contextual detail that would be too mundane to publish on its own.] Our bags were unloaded and trucked to Exeter from Felixstowe and the Cosco Pacific sailed on to Hamburg to continue its journey.

6. Ship spotting in Singapore

Let’s go back to Singapore. We’d been posting the Cosco Pacific’s travels live on twitter and noticed that it was docking in Singapore. On the Marine Traffic Google map, we were fascinated to see that the National University of Singapore (NUS) campus was right next to the port. So we asked in a tweet if anyone working there could pop down and see if they could see our ship. NUS Geographer Tim Bunnel got back to us: “The campus of the university in Singapore where I have been based for the past 12 years or so is flanked at its southern edge by Pasir Panjang Road. This Malay road name means ‘long sands’ and, not surprisingly, took its name from the coastline in this south-western part of the island. However, working at the National University of Singapore’s Kent Ridge campus today, it is easy to forget that you’re on an island at all. Land reclamation means that the coastline is several hundred meters away from Pasir Panjang Road and the few remaining bungalows there which once backed onto the beach. What is more, the container port facilities that now define the coastline are, for the most part, invisible at the ground level. When I went to look for the Cosco Pacific, reportedly berthed somewhere along the west coast, I headed to West Coast Park. My wife and I often take our dogs for walks there and it happens to be the one remaining section of the coastline where it is possible to get a ground-level view of the container ships that account for Singapore being one of the busiest ports in the world. Unfortunately, at 7 am during a period when Singapore is still being affected by ‘the haze’ from forest fires in neighbouring Indonesia, visibility was very poor this morning. I could make out a ship at the western end of the container port (see first photograph), but I don’t think that it was a Cosco ship. I have seen their ships before and they have ‘Cosco’ written on their side in big enough letters to be visible from that distance, even on a hazy morning. After I gave up trying to photograph ships from a distance through the haze, I decided to walk along the edge of the park, as close as possible to the coastline. Swarms of small motorbikes were buzzing along the road carrying port workers from Malaysia who commute across the border. Unlike them, I was not authorized to enter the port area and, instead, walked along its perimeter looking for parts of the fence where I thought that it might have been possible to get a glimpse of more ships. As it turned out, all I could see was stacks of containers. The second photograph shows a Cosco container but, again, there is no way for me to tell if it came from the Cosco Pacific. I walked back home thinking – not for the first time – about how different things must have been before containerization. The Malay ex-seafarers in Liverpool whose lives I have been writing about (see: http://www.fas.nus.edu.sg/rg/html/geog/tbindex.html) recall a very different Singapore where there was no clear boundary between port and city life, and when it was still possible to walk on sand beside Pasir Panjang Road.’

7. Delivery

The bags eventually arrived in a truck at the University of Exeter in October 2011, where two pallets were unloaded. 50 boxes were delivered, each containing 100 neatly folded bags. The two delivery men seemed taken aback at how excited I was to receive them. But this was a wonderful moment. We opened the boxes to see what we’d designed and ordered in their full, realised, ‘pp woven’ glory. It was amazing. The look. The feel. Our design. Realised. Exactly as we had wanted it to be. But there was more to do. We wanted to get them in circulation. So, we arranged to give them away, first, to anyone who visited our website and found that they could ask for one (or a box of 50 for their class) and, second, as free conference bags at the 2012 Geographical Association and Royal Geographical Society conferences. At the GA’s Annual Conference in April, 900 bags were given away. The GA is the subject association for Geography teachers in the UK and it was important to get the word out in the community in the hope that it, and the followthethings.com website, could help to teach the geographies of trade in UK schools. Supported by some talks and teacher-facing publications, this is what happened (see Anon 2014).

8. Another kind of shopping bag

Four years later, all 5,000 were in circulation. I once saw someone carrying one on the Tube in London. People were using them, inserting them – if you like – into the ideological circuits of shopping (see Meireles 2009, Demos 2010). They were the same as other bags, but there was more life in them: life we found in factory audits, ship tracking, port stories, and their delivery, as well as the life we put into them (see Luke 2000, Bennett 2000). They were also bags of ‘counter-information’ because they were explicitly designed for both kinds of ‘shopping’ (see Meireles 2009, Demos 2010). When people brought them home, full, from the shops, we asked them to research their contents and send us a photo and their findings to put in that flickr album mentioned on the bag. Here’s one we posted to start this off:

This exemplar bag had school shirts from Marks & Spencer, a Tangle Teezer hair brush, Moshi Monsters trading cards and a Spongebob magazine. Added below the photo were links to a 2011 online magazine article about Marks & Spencer’s use of fair trade cotton and a 2007 ActionAid report critical of school uniform supply chain; a 2011 online newspaper report about the Tangle Teezer’s failure to gain financial support on TV’s Dragon’s Den; and 2011 online newspaper reports about the takeover of the magazine’s publisher by venture capitalists and their subsequent winding up of workers’ pension scheme [as before, no trace now exists of these news stories online].

The point that this ‘bagful’ photo and the detective work into its contents was supposed to illustrate was that, within even the most innocent commodity, there are hidden stories of labour that can, relatively easily, be found and published online (Cook et al 2007) by people working not only at followthethings.com HQ but also at 5,000+ other locations worldwide. We didn’t get the deluge of photos and detective that we were hoping for in our flickr album, but that didn’t mean people weren’t trying this out.

9. Ladybugging

This wasn’t the only way these bags could be used to disrupt the act of shopping. In January 2012, a craft group started meeting in the cafe along the corridor from my office in the Amory Building at the University of Exeter, which was linked to an AHRC-funded research project on Craft Geographies. Academic staff, postgrads, technical staff and others came along to talk and knit. I’m not a knitter, but I donated a box of 50 followthethings.com shopping bags as ‘craft materials’ and went to the meetings to join in the conversation. We discussed what we should do for international yarnbombing day – the first day of Spring – and ended up knitting and cutting out of our bags a large number of ladybirds to yarnbomb the entrance to the Amory Building (craftgeographies 2012a).

These ladybirds, bags and other materials, images and stories fired our imaginations, mischievously, hilariously and, we thought, with some critical purpose our ‘shoppers’ might enjoy participating in (cf Treadaway 2009; Merrifield 2011; Cook & Woodyer 2012, Woodyer & Geoghegean 2012). The ‘sympathetic character’ at the centre of our activism would not a person but a printed ‘pp-woven’ ladybird (Canning & Reinsborough 2012). In its short life, each of the insects printed onto our shopping bags had witnessed global trade first hand, seen and heard factory workers, dock and ship workers, truck drivers and their mates, all over the world, at close quarters. followthethings.com ladybirds knew about supply chain labour and their experiences had given them powerful bugging capabilities. Released from the bags, and out into worlds of shopping, they would watch, notice and wonder. The activism where a commodity gains consciousness and tells its audiences what trade is like from its life story perspective is called an ‘it-narrative’. This is the oldest genre work that we have found, with examples dating from as early as 1752 (see our page on a book called Chrsyal; or, The Adventures of a Guinea).

For other examples of trade justice activism where the commodity becomes the character commenting on what they see, click here.

To promote the creation our our ladybirds’ ‘it-narratives’, we published on the followthethings.com blog a ladybird release (and bag patching) guide (Cook et al 2012a) and started to take individual ladybirds out shopping. We offered conference and student ladybugging workshops. We gave each participant a brand new bag and a pair of scissors, told them the life story of our bags and what they had seen, and asked people to set one ladybirds free and take it outside to look around. We suggested holding it in one outstretched hand, head first, as if you were following its flight. We asked people to imagine what this ladybird had seen in her short life, what she knew, and what she would notice and think when she saw what they saw. When she directed them towards something, we asked them to place her on or near it, take a photo, create a caption and a narrative and share it with us back in the classroom. Below are some of the examples we used to show people what we were looking for.

It’s fascinating to walk through a university campus or a shopping centre with a plastic ladybird in your hand. Holding her up in front of your phone camera lens, getting the shot just right, can attract attention. Possibly from security guards. You might be asked what you’re doing. You could explain in great detail, or simply say it’s an art project. I was once approached by a security guard at a Manchester shopping mall for acting suspiciously outside an Apple Store. In practice, this gentle activism not only calls into question your own taken for granted shopping mindsets and behaviours, but it also disrupts them for other shoppers, shop workers and security guards. Artist Louise Ashcroft calls this activism ‘retail sabotage’ and what she says about this is hilarious and thought-provoking (see Regine 2017).

10. Catching on

This creative playful, imaginative, critical making approach to trade justice activism tries to engage its participants and wider publics in critical discussions of contemporary capitalism by appropriating everyday social forms, providing materials and ideas with which to imagine and create new forms, and encouraging and sharing the results of this collective creativity for others to enjoy, be informed and inspired by, on- and offline (Bishop 2006, Beuys & Schwarze 2006). After all these years, this is still a work in progress for us. The bags are still out there. We wonder if we should make some more. The bagful detective work and the ladybugging has and hasn’t caught on. But, we tell ourselves, any shopping bag has the potential to be thought about and used like this. You can research who made the contents of any bag of shopping. There’s so much investigative journalism and NGO reporting online now. And you can cut out creatures from any reusable shopping bag and take them shopping. We’ve done this with Tesco mosquitos and Sainsbury’s elephants too. We reckon we know what that mosquito might think. And the elephant: he remembers everything.

Page created in September 2024 by Ian Cook from previous followthethings.com shopping bag posts (Cook et al 2011, 2012b, 2013). Thanks to Daisy Livingston, Aiden Waller, Jack Parkin, Emma Christie-Miller, Alice Goodbrook, Doreen Jakob, Angela Last, Tara Woodyer, Chris Bear, Sarah Mills, Amanda Rogers, Becky Sandover and Mia Hunt for helping to shape the arguments made here.

Sources

Anon (nd) Shop. dictionary.com (http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/shop last accessed 17 July 2011)

Anon (2014) ‘Follow The Things’: developing critical pedagogies to promote geographically-informed and ethically-aware consumption in school geography curriculum. (https://impact.ref.ac.uk/casestudies/CaseStudy.aspx?Id=36401 last accessed 12 September 2024)

Beuys, J. & Schwarze, D. (2006) Report on a Day’s Proceedings at the Bureau for Direct Democracy // 1972. in Bishop, C. (ed). Participation. London: Whitechapel Gallery, 120-4

Bennett, J. (2001) The enchantment of Modernity. Princeton: Princeton University Press

+17 sources

Bishop, C. (2006) Introduction // viewers as producers. in her (ed) Participation. London: Whitechapel Gallery, 10-17

Canning, D. & Reinsborough, P. (2012) Lead with sympathetic characters. in Boyd, A. (assembler) Beautiful trouble. New York: O/R Books

Cook et al, I. (2011) Bag designs. https://www.flickr.com/photos/followthethings/albums/72157629758249393/with/5941041430/ (last accessed 11 September 2024)

Cook et al, I. (2012a) Craft work with followthethings.com shopping bags. A 12-step guide to releasing your ladybirds and repairing your bag for use again and again. (https://followtheblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/ftt-bag-repair-guide-feb-2012.pdf last accessed 12 September 2024)

Cook et al, I. (2012b) Follow the bags: pulling together the travels of the followthethings bags. http://storify.com/followthethings/following-followthethings-bags (last accessed 31 December 2017)

Cook et al, I. (2013) Happy ‘shopping’: making & using followthethings.com bags. https://followtheblog.org/2013/09/18/happy-shopping-making-using-followthethings-com-bags (last accessed 11 September 2024)

Cook et al, I (2014) Fabrication critique et web 2.0: les géographies matérielles de followthethings.com. Géographie et cultures, 91-92, 23-48 [English version here]

Cook et al, I (2017) followthethings.com: analysing relations between the making, reception and impact of commodity activism in a transmedia world. In Söderström O, Kloetzer L (Eds.) Innovations sociales: comment les sciences sociales transforment la société, Neuchátel, Switzerland: University of Neuchátel, 46-60

Cook, I., Evans, J., Griffiths, H., Mayblin, L., Payne, R. & Roberts, D. (2007). ‘Made in… ?’ appreciating the everyday geographies of connected lives?. Teaching Geography (Summer), 80-83

Cook, I. & Woodyer, T. (2012). Lives of things. in Sheppard, E., Barnes, T. & Peck, J. (eds) Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Economic Geography. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 226-241

Demos, T.J. (2010) Another world, and another. in Farquharson, A. & Waters, J. (eds) Uneven geographies. Nottingham: Nottingham Contemporary, 11-19 (download from http://www.nottinghamcontemporary.org/art/uneven-geographies)

Hawkins, H. (2011) Dialogues and doings: sketching the relationships between Geography and Art. Geography compass 5(7), 464-78

Ingold, T. (2007) Materials against materiality. Archaeological dialogues 14(1), 1-16

Last, A. (2012) Experimental geographies. Geography compass 6(12) 706–724

Luke, T. (2000) Cyborg enchantments: commodity fetishism & human/machine interactions. Strategies 13(1), 39-62

Meireles, C. (2009) Notes on Insertions Into Ideological Circuits // 1994. in Doherty, C. (ed.) Situation. London: Whitechapel Gallery, 121-2

Merrifield, A. (2011) Magical Marxism: subversive politics and the imagination. London: Pluto Press.

Regine (2017) Vegetable smuggling, grimy goods and other retail sabotages. An interview with Louise Ashcroft. (https://we-make-money-not-art.com/vegetable-smuggling-grimmy-goods-and-other-retail-sabotages-an-interview-with-louise-ashcroft/ last accessed 12 September 2024)

Image credits

Sainsbury’s bag: Helophorus dracomontanus (10.3897-zookeys.718.21361) Figure 2 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Helophorus_dracomontanus_%2810.3897-zookeys.718.21361%29_Figure_2.jpg) by Christian Ferrer (CC BY 4.0) Modifired September 2024;

Tesco bag: tesco bag for life (https://flic.kr/p/fcyGJE) by ambernectar 13 (CC BY-ND 2.0).

All other images: followthethings.com.

![]()